One hundred years ago, at New Year 1925, Italy became the world’s first fascist dictatorship.

Are there any parallels from what happened then to today’s developments in the United States?

Photo: Screendump

by Jonas Bals, author section leader at LO

(Photo: Byggmesteren / Christopher Kunøe)

Original first published in Norwegian in Agenda Magasin February 8., 2025

When Benito Mussolini became the leader of a bourgeois coalition government in 1922, it marked the start of what would become a 20-year fascist dictatorship. When the king appointed him prime minister, he repeated his assurances that the bourgeois parties had nothing to fear. The labor movement was to be the only one to feel the weight of the fascists’ iron heel.

Now the fascists wanted to “bring life to the people’s souls newly awakened by the war”.

Two and a half years later, there were no more parties other than the fascist one, and democracy was gone.

Shortly after becoming prime minister, Mussolini requested a mandate that gave him almost unlimited freedom of action for a year. In parliament, everyone except the socialists voted in favor. The Fascist Party then conquered large parts of the state apparatus and gathered most of the real power in its own body of power, the Great Council of Fascism, the Gran Consiglio.

“The fascists are completely masters in most of the country,” wrote the Norwegian Morgenbladet.

Now, the fascists wanted to “bring life to the people’s souls newly awakened by the war.”

Much coercion and censorship were carried out without the use of physical force.

“The tyrant in the seat of power” was the headline in Trøndelag Social-Demokrat, which, like other workers’ newspapers, understood what was about to happen. They did not share Morgenbladet’s and Aftenposten’s enthusiasm.

They wrote, “With Mussolini begins a new phase in the history of capitalism: the anti-parliamentary, anti-socialist, imperialist policy carried out with open violence inwards.”

Benito Mussolini was in power in Italy from 1922 to 1943.

The concealment and repression that followed took many forms. The anarchist Errico Malatesta, for example, was put under house arrest and died as a completely isolated man whom no one dared to greet. Anyone who sought him out was arrested, and police officers stood guard outside his house 24 hours a day.

Morgenbladet, for its part, was able to report on several fortunate side effects of the fascists’ plans to privatize the public sector.

Much coercion and censorship were carried out without physical force: the newspaper owners themselves saw to it that they fired editors and journalists who were too critical of Mussolini, and self-censorship was far more widespread than censorship.

The violence that had characterized fascism when it was a street movement financed by Italy’s wealthiest men did not cease, however. It was at least as intense after it disappeared from the streets and was instead moved into the prisons and fascist headquarters.

But because it was also so quiet, it was easy to overlook for anyone other than those unlucky to experience it firsthand. As historian John Foot writes in Blood and Power, fascism was “the triumph of silence. “

This is an edited extract from the book “Our Battles”

In Aftenposten, it was said there had been a “peaceful revolution in Italy these days.” The nosebleed admiration the newspaper expressed was to persist through most of the interwar period:

“Militarily organized. Excellently organized. […] Parliamentarism could not save Italy; the parliamentarians fight among themselves, and for most of them, the small interests of the party mean everything, the great life story of the fatherland means nothing. We know it so well from our own Parliament.”

Morgenbladet, for its part, reported on several fortunate side effects of the fascists’ plans to privatize the public sector. Although the Fascists’ first manifesto used almost left-wing radical language about nationalization, the Italians received something completely different with Mussolini in power.

Norwegian Dagmar Engelhart, who lived in Rome, wrote five correspondent letters for Morgenbladet in November 1922. In them, she praised Mussolini’s reforms, such as privatizing railways, telegraphy, and telephony. In addition to changing the electoral law and abolishing 19 public holidays, the regime dismissed many public employees, or “parasites,” as Engelhart called them, under the slogan “fewer and smarter people.”

Mussolini reduced the state’s economic role, cut taxes, and cut public spending.

This not only relieved the state of expenses and the taxpayers of burdens but also made life easier for upper-class wives like Engelhart:

“It is believed that this last reform can also make up for the lack of domestic help, which has been so noticeable here in recent years. Many of the dismissed civil servants in the public offices are young girls who were content to be maids in the past, and the housewives now hope that they will have to return to this work.”

Socialist parliamentarian Giacomo Matteotti described how the fascists’ barely three-year-old program from 1920, which had called for the confiscation of “unproductive” war profits and the introduction of inheritance tax, was a pipe dream:

The fascists’ first exemption laws, on the contrary, were to exempt large fortunes from taxation, halve the tax rates for directors and chairmen, halve VAT on perfume and jewels, and so on. Adopting an inheritance tax was also resolutely rejected:

In decree no. 1802, from August 1923, it was said that “fascism is also, and above all, inextricably linked to respect for the family and the Roman concept of property.” Alberto De Stefani was Mussolini’s first finance minister. He reduced the state’s role in the economy, cut taxes, and reduced public spending.

Mussolini elevated illegalities to law and raised “criminal morality to national morality. – Ingeborg Refling Hagen, Norwegian author and anti-fascist

Despite Mussolini’s anti-capitalist rhetoric, he allowed industrialists to do as they pleased, at least until Italy converted to a war economy a few years later. In addition to cutting taxes on business, the Fascists allowed powerful cartels to dominate the market, accepted wage cuts for workers, and reversed the eight-hour workday.

In 1922–24, Italy was what we would today call an “illiberal” or “managed” democracy, in which the opposition was gradually rendered powerless and passive. For the working class, the country had long since become a dictatorship, but the other bourgeois parties were allowed to live on for the time being.

In April 1924, the last elections in over twenty years were held.

Jonas Bals. Photo: Siw Pessar.

In his book Un anno di dominazione fascista (“A Year of Fascist Domination”), Giacomo Matteotti documented how the fascists’ “neoliberalism” – the term was their own – looked in practice.

He wanted to show that the state had never been so unilaterally subordinated to a small group, that the law had never before been so grossly disregarded, and that the country had never been so divided into two classes, “a dominant and a subordinate class.”

He also showed how wages had fallen, and profits had risen while there had been 90 percent fewer strikes in one year. The fascist state was not only an oligarchy, it was also a plutocracy – a robber state. One of those who witnessed this firsthand was the Norwegian author and anti-fascist Ingeborg Refling Hagen, who in her book Utenfor balkongen (1936) described the first phase of fascism.

She described Mussolini as a “mob king,” both feared and respected by the masses, who ruled with the help of two types of mafia, “simple and fine.” The former indulged in violence and bloodshed, while the latter “has occupied prisons and judicial offices” and was about to occupy “every position that exists in all of Italy.”

Mussolini elevated illegalities to law and raised “criminal morality to national morality,” she believed.

Giacomo Matteotti also investigated allegations that the fascists were engaging in widespread misuse of public funds.

Mussolini’s political police, the Organizzazione di Vigilanza e Repressione dell’Antifascismo (OVRA), was not only used against regime opponents and anti-fascists but also to identify those close to him. The OVRA kept a close eye on the extensive corruption in archives in Mussolini’s private office.

The intelligence was not conducted to clean up corruption and bribery but to secure loyalty and to be able to blackmail if necessary. The archives survived the war and show how fascism was also a criminal enterprise, a business model based on the misuse of public funds and private enrichment in which almost all of Mussolini’s inner circle was involved.

Overtime bonuses were more than halved, the typical working day was extended by two hours, and the budgets of the labor inspectorate were cut. Unfair dismissals were legalized, and immediate dismissal could be granted on grounds such as “unconstitutionalism” and, for some female workers, “immorality”.

Mussolini initially declared that he would not give women the right to vote as he had previously promised but realized that this, too, could be a means of fascist upper-class dominance. In local elections, women were therefore given the right to vote, but strict requirements for education and wealth ensured that only middle- and upper-class women were allowed to vote.

Matteotti never made it to London

By destroying the free workers’ cooperatives, the fascists realized “one of the greatest dreams of shopkeepers and speculators” and, at the same time, removed one of the most effective means of combating rising prices.

Socialist parliamentarian Giacomo Matteotti.

The Fascists represented “the bitterest opposition of the propertied classes to the idea of balanced budgets,” Matteotti wrote, particularly their opposition to increased taxes. Wealthy Fascists had organized taxpayer strikes and also financed the first gangs that waged civil war against the Socialists.

Matteotti also investigated allegations that the Fascists were involved in widespread misuse of public funds. This involved billions of lire in tax evasion, the privatization of state-owned companies, and falsified bank bailouts.

Matteotti also learned from union comrades in London that they were holding out revealing details about the Italian government’s contracts with Sinclair Oil. This American oil company was gaining a monopoly over the country’s oil resources.

January 3. 1925 : The day has been considered by many to be the birthday of the world’s first fascist dictatorship.

Matteotti planned to travel to London and look at the documentation in more detail.

Matteotti never made it to London.

On June 10, 1924, the 39-year-old father of three and parliamentarian was attacked on an open street in Rome and dragged into a car. Among those sitting there were Mussolini’s former bodyguard, Albino Volpi, Amerigo Dumini, and several others. The vehicle, which was later found parked outside the Ministry of the Interior, bore clear marks from the violence that followed. One of the windows was broken, and the back seat was bathed in blood.

Matteotti was probably stabbed to death before the perpetrators stripped him to his underwear and buried him in the deserted forest area of Quartarella outside Rome. The kidnapping sparked strong reactions across the country, and 130 opposition politicians resigned from their posts in protest.

On January 3, 1925, a hard-pressed Mussolini stormed into parliament with a small battalion of fascists. Many wondered if he would throw in the towel and if the king would have to find a new prime minister.

Instead, Il Duce threw all tendencies towards a policy of reconciliation overboard.

Even the bureaucracy left the fascists largely intact.

“If all acts of violence have been a consequence of the historical, political, and moral atmosphere, then the responsibility rests with me since it was I who, through my propaganda, created this historical, political, and moral atmosphere right from the time we entered the war,” he declared.

The day has been considered by many to be the birthday of the world’s first fascist dictatorship.

In the next six months, another wave of terror swept across the country. The last free newspapers were confiscated, associations were dissolved, and the trade union movement was annexed. Political opponents who did not give up or go into exile were imprisoned or killed. The bourgeois liberals continued to adapt to the course of events and, among other things, agreed to an electoral system that aimed to create a “national bloc” with a fascist core. Thus, it was, in effect, a thank you and farewell to them too.

The fascist party and the state merged into a single entity, becoming a party state. It was a strange construction, built on the liberal state, which formally lasted for the years that followed: Mussolini remained prime minister, appointed by the king, and the constitution remained the same. The king continued to be both head of state and leader of the armed forces.

Even the bureaucracy left the fascists largely intact.

Formally, the German Nazis never abolished the Weimar Republic’s constitution of 1919, they simply suspended it.

The police were given formal powers to send people into internal exile (confino) for up to five years based on nothing more than a suspicion of subversive activities. The law rejected the principle of individual freedom as the foundation and goal of society and instead put the protection of the state first. The state was considered an independent organism with its own life, in line with the ideas of an “organic state” formulated by the German geologist Friedrich Ratzel in 1897.

Strikes and slow-motion actions were banned, and workers were no longer allowed to be represented by their own elected representatives. Instead, they were to be represented by professional middle managers in The National Fascist Party (Italian: Partito Nazionale Fascista, PNF), who often had middle-class backgrounds and had little sympathy for the workers they were supposed to speak for. Wages fell, and employers were, in the words of historian Christopher Duggan, given the whip back in their hands.

That’s not how coups are done today, writes Snyder.

What Mussolini took about ten years to accomplish in Italy, Hitler managed to do in a few months in 1933. When he became head of a bourgeois coalition government in Germany, he quickly implemented what the Nazis called a “Gleichschaltung.”

It was originally a technical term for rectification in electrical engineering, transforming alternating current into direct current, but was used to describe the standardization of the German civil service.

Formally, the German Nazis never abolished the Weimar Republic’s constitution of 1919, they suspended it – and made sure to bring all those who resisted to their knees. On March 31, 1933, the first Gleichschaltungsgesetz came into effect, dissolving the state parliaments, and on April 7, the second Gleichschaltungsgesetz followed, giving all states except Prussia a Nazi Reichsstatthalter.

In 2025, many wonder if it is the United States’ turn. The only thing that is predictable right now is that everything is unpredictable. But it is not without a plan. If you are going to be able to predict what might happen and make plans to prevent it, it is wise to learn from history. But you should also not stare blindly at it, hoping it will repeat itself. It does not. But sometimes it rhymes.

“Imagine if it happened like this,” writes historian Timothy Snyder this week.

“Ten Tesla cyber trucks, painted in camouflage colors with a giant X on the roof, drive through Washington, D.C. A couple of dozen young men jump out of the cars (…) After greeting each other with the Nazi salute, they pick up their weapons and run to one government department after another, while shouting slogans like ‘all power to the Supreme Leader Skibidi Hitler.’”

That’s not how coups are done today, Snyder writes. And if they did, we would recognize it for what it is.

Author and professor Timothy Snyder. Photo: Stephan Roehl/Flickr cc

But imagine this instead:

“A couple dozen young men go from government office to government office, dressed in civilian clothes and armed only with zip drives. Using technical jargon and vague references to orders from above, they gain access to all the basic computer systems of the federal government. Having done so, they give their top leader access to information and the power to start and stop all government payments.”

That’s what’s happening in the United States right now. As I write this, a coup d’état is underway, and I wonder if our understanding of history is preventing us from understanding it. Because the form is different, we don’t believe what we see with our own eyes or hope for the best. It’s not exactly like it was in 1925 or 1933.

If Americans are going to be able to do something about this before it’s too late, it’s urgent. In the meantime, the rest of us must prepare to work in solidarity with the country’s democratic forces.

They will need all the help and support they can get.

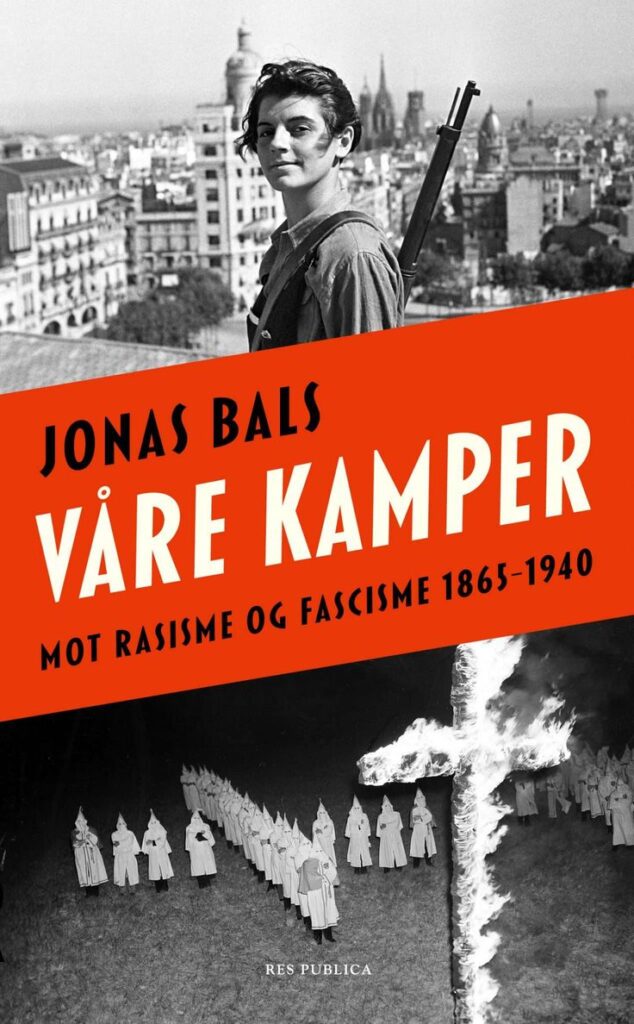

(This is an adapted excerpt from the book “Our Battles,” published by Res Publica. Agenda Magasin, which first published this article, and Res Publica are part of the same company.)

Elon Musk’s henchmen at DOGE who are actively participating in this coup include:

— Barbie Girl (@barbiegirl420.bsky.social) February 6, 2025 at 8:20 PM

• Josh Gruenbaum

• Russell “Rusty McGranahan

• Akash Bobba

• Marko Elez

• Luke Farritor

• Gautier Cole Killia

• Gavin Kliger

• Ethan Shaotran

• Nicole Hollander

• Branden Spikes

BREAKING: A government worker reports that fresh-faced 19, 20, and 21-year-olds from DOGE are running 15-minute kangaroo courts to decide if federal employees keep their jobs.

Bureaucracy just turned into an episode of Shark Tank, but with interns holding the gavel. pic.twitter.com/a608dzs8KG

— Brian Allen (@allenanalysis) February 8, 2025

5 Comments

Pingback: Elon Musk : Der Tesla-Mensch und sein Swasticar - Bergensia

Pingback: Toxic Wealth. When oligarchs want to remake society in their image, the far right is a natural tool - Bergensia

Pingback: IT'S A COUP - Bergensia

Pingback: What a strange world where Nazi salutes are pro-Israel and humanitarian law is antisemitic - Bergensia

Pingback: Trump banning ANTIFA what does that make him? - Bergensia