Bumble Dee/Shutterstock.com

John Broich, Case Western Reserve University

Since U.S. troops left their region, roughly 180,000 Kurds of northeastern Syria have been displaced, and over 200 have been killed.

Those Kurds, soldiers who’d battled the Islamic State and families, had hoped to secure a future Kurdistan state in areas now targeted by Turkish warplanes and patrolled by Russian mercenaries.

This is only the latest reversal for the Kurds, a group of around 40 million who identify with a regional homeland and common historical background, but are now divided between four countries. Despite their many attempts, there’ve never won and kept a Kurdish nation.

Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection at The University of Texas at Austin

Drawing borders after WWI

The most decisive reversal came at the end of the first World War. That’s when the Allies, victors over Germany and the Ottoman Empire, divided their geographical spoils of war.

In a series of conferences in a succession of European palaces, Prime Minister David Lloyd George, Georges Clemenceau of France, Woodrow Wilson and dozens of other leaders conspired, harangued and horse-traded from 1919 to 1921. Under clouds of cigar smoke, between servings of foie gras and champagne, they redrew a large swath of the globe’s map.

Besides doling out spoils to themselves, such as far-flung German imperial holdings, their aims were to replace the Austro-Hungarian Empire, punish Germany in Europe and – the biggest task – fill the vacuum left by the demise of the sprawling Ottoman Empire, which before the war covered territory from the edge of Bulgaria to Yemen.

Their guiding principle for redrawing the map, at least in most cases, was the reigning concept of race nationalism, what’s often called today ethno-nationalism.

Simply put, the Allies’ delegates assumed that nation states should be composed as much as possible by single “races,” single ethnic and linguistic populations. So, they defined, in some ways created, new races – like, for example, Hungarians or Austrians – and drew borders around them.

Who should receive an ethno-state?

What to do in the big, central zone of the defeated Ottoman Empire, stretching between the Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf?

Should there be one big, Greater Arabia or Arab federation, as some British officials promised their Arab allies who revolted against the Ottomans? Should there be many little nations, with borders around Christian Arabs, Muslim Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Kurds? (Following their race-nation instinct, the British did support what they called a new “National Home for the Jewish people” in former Ottoman Palestine.)

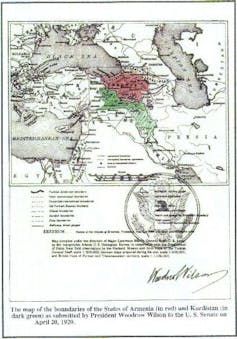

That, too, is what President Woodrow Wilson’s call for self-determination dictated. Wilson himself was explicit in calling for a new, broadly encompassing Kurdistan.

Ara Papian/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

They took for granted that Kurds were a race and that Kurdistan was a place. In fact, it was already depicted in pre-WWI atlases. The problem of drawing its borders fell, British Parliamentarians told themselves, to them in immediate postwar years. And it’s what some powerful people in British officialdom assumed would happen.

Not only did it fit British race thinking to create Kurdistan – to be heavily staffed by British “advisers” like the other new states, of course – but they believed the Kurds truculent and independent, unlikely to accede to domination by a neighbor.

They would “never accept an Arab ruler,” in the words of one British Colonial Office official, if they were embedded in an Arab nation.

A missed opportunity

But the Allies and the League of Nations never created Kurdistan. Why not?

British imperial self-interest in this case overruled ethnonational thinking. By the terms of the Sykes-Picot agreement, the secret French and British understanding of roughly who would get what after the war, the French claimed dominance of the northern Levant, what’s today Lebanon and Syria.

The British wanted a big geographical bloc in the region to match that of the French, to act as a counterweight. They formalized this by inventing a large country soon dubbed “Iraq.”

The line dividing Sykes-Picot’s French sphere and British sphere already cut straight through Kurdish areas. That partition was part of the reason why the British could not simply carve out a new, large Kurdistan (that they’d dominate like Iraq).

Mahmoud Abu Rumieleh, Webmaster/Wikimedia, CC BY

For another, British colonial officials, like the famous writer-turned-colonial administrator Gertrude Bell, wanted a Kurdish population retained in the new Iraq as a counterbalance to its large Shiite population, which was deemed seditious.

This represented classic British imperial thinking long employed in places like India: divide and conquer. The Kurds might not be particularly docile or loyal to the British, but they could be counted on not to unite with the Arabs or Assyrians, either, and throw off British meddling.

The British, too, suspected there were large oilfields under the important Kurdish capital of Mosul. Better to keep the Mosul region securely within Iraq, some leaders judged.

That colonial-era behavior had a recent analog, when President Donald Trump said that the Kurds could be allowed to remain near oilfields in far eastern Syria to protect them against the Islamic State. They’re still useful, it seems, for maintaining order above oil.

The roots of the trouble with Turkey

The Allies’ last, half-hearted attempt to create at least a small Kurdistan took place during yet another conference of the Allies in the Paris suburb of Sèvres in 1920.

Planned for eastern Anatolia, or Asia Minor, squeezed into borders to which the Kurds objected as too little, this Kurdistan came to naught. The new, revolutionary nationalists in Turkey wanted their own race-nation of Turks. And they did not want Anatolia chopped up for the sake of Kurds or Armenians. They’d simply have to become Turks, too, or face the consequences.

From 1920, the new Turkish Army occupied what was to become the little Kurdistan, and the Allies had no will to challenge them. The last hope that WWI’s victors would create even a fractional Kurdistan disappeared without fanfare.

But the Kurds didn’t stop – have never stopped – resisting. When the British lumped them into their invented country of Iraq, the Kurds naturally revolted in 1919. When a delegation of British colonial authorities arrived to parley with the Kurdish leader, Sheikh Mahmoud Barzinji, the man calmly quoted Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, with its call for the “autonomous development” of the peoples formerly dominated by the Ottoman Empire. The British responded with two brigades.

Now, as then, it seems world powers support Kurd’s self-determination only until it’s no longer expedient.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

John Broich, Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.