Exposing the secret history of the making of the climate crisis should change everything about how we act to stop it.

by Julia Steinberger, Immigrant, Swiss-American-UK ecological economist at the University of Lausanne. Research focus on living well within planetary limits. Original published by the author on Medium.

An upheaval in 10 chapters:

- The cause. We know the climate crisis is brought to us by highly unequal and undemocratic economic systems.

- The rise. The recent history of these economic systems in the Americas and Eurasia is dominated by the ascendance of neoliberal ideology.

- The threat. Neoliberal ideology is antidemocratic at its very core. Its aim is to give free-reign over our societies to corporations, not citizens.

- The promoters. The fossil fuel industry is a long-time promoter, as well as beneficiary, of the neoliberal takeover of our societies.

- The coordination. The organisation of this takeover is not haphazard: it is coordinated through think tanks, lobby groups, public relations, and legal firms. These, in turn, are coordinated internationally, for instance, via the Atlas Network, which is involved in more than 500 think tanks worldwide.

- The buildup. These think tanks train their cadres internally and promote them to places of influence in policy and communication.

- The message. These think tanks replicate their materials and strategies worldwide. Their poisoning of our public sphere runs the gamut from advocating brutally unequal neoliberal economic policies to promoting climate science denial. They also dabble in divisive culture war topics, on gender (equal rights for women, queer & trans rights), race or migration, for instance.

- The influence. One core goal of these organizations is to replace university research expertise with their own materials, influencing the influencers, with journalists and teachers identified as prized targets.

- The implication. To counter such centralised and coordinated actors, the climate movement (and indeed all movements attacked by neoliberalism) should change radically, both in orientation and strategy.

- The direction. Democracy, the fearsome foe of neoliberalism, should be at the heart of our new direction.

A couple of disclaimers to start.

- This essay will be short (compared to its scope) to enable as many people as possible to read it. This is not a scholarly treatment but a bar-room pitch. Inaccuracies are inevitable.

- However, I am going to link and cite the main works and ideas I draw upon so people can look up, verify, and correct my main claims.

- I am not an expert in most topics here. My pledge is to make this a living document: if & when I need to correct it, I will make tracked updates.

Let’s go.

Chapter 1. The cause.

The climate crisis is brought to us by highly unequal and undemocratic economic systems.

This has been covered and evidenced over and over, so I will just restate the main points: the climate crisis is a crisis of wealth accumulation. The wealthiest emit the lion’s share of global CO2 emissions, while owning and benefiting from the fossil fuel industry and its allies.

In this economic system, economic growth accrues to the wealthiest, exacerbating both climate and social crises of inequality. The wealthiest grow ever more wealthy and powerful: powerful enough to constrain our economies into continued fossil fuel dependence, despite the social, economic, health and planetary harm this dependence causes. Fossil fuel dependence is imposed upon us by diverse undemocratic mechanisms, ranging from enforcing car-dependency through segregated and inefficient urban planning, all the way to international trade treaties protecting fossil fuel profits (like the Energy Charter Treaty). This unequal and antidemocratic interference of the fossil fuel industry in our societies is more than a century old, dating all the way back to Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, now ExxonMobil.

Chapter 2. The rise.

The recent history of these economic systems, in the Americas and Eurasia, is dominated by the ascendance of neoliberal ideology.

Neoliberalism was the brainchild of the Mont Pélerin Society, a clique of economists intent on beating back the (relatively) egalitarian stability of Keynesian economics. In the 1950s, they came together, led by Friedrich Hayek, to devise the contours of an economic program where corporations would be freed from the tyranny of basic social responsibilities.

Although neoliberalism cloaked itself publicly under a mantle of “market freedom as underpinning other freedoms”, it is really important to understand that the freedom it promotes is freedom for producers (i.e. private firms and capital owners) only, not for any other economic actors. Not for workers, not for consumers, not for citizens, not for communities. The goal is full power and range of action for producers, while curtailing the ability of other actors to come together to make any kinds of economic demands or changes.

Chapter 3. The threat.

Neoliberal ideology is antidemocratic at its very core. Its aim is to give free-reign over our societies to corporations, not citizens.

This is probably the part of this essay that will be the most counter-intuitive. Many people, including those politically active in liberal or neoliberal spheres, consider themselves to be pro-democracy, while upholding market freedoms. And many on the left, including myself, considered neoliberalism to be obsessed with free markets, to the detriment of democracy. But that understanding gets neoliberal cause and effect backwards.

As Wendy Brown masterfully tells the story, in her epic “In the Ruins of Neoliberalism,” Hayek’s neoliberal edifice starts, at its foundation, with a determination to destroy society, and democracy, understood as the ability of people to make common claims about their goals and aspirations. The imposition of market absolutism is a merely a means to an end: the goal is the destruction of democracy. Again, I understand if this seems strange, but it is true. In Hayek’s own words, quoted by Brown:

The more dependent the position of the individuals or groups is seen to become on the actions of government, the more they will insist that the governments aim at some recognizable scheme of distributive justice; and the more governments try to realize some preconceived pattern of desirable distribution, the more they must subject the position of the different individuals and groups to their control. So long as the belief in “social justice” governs political action, this process must progressively approach nearer and nearer to a totalitarian system.

In Hayek’s world-view, democracy leads inevitably to a collective claim towards “distributive justice”, some form of universal need satisfaction. And this collective claim, rather than being understood as a reasonable collective goal that we should indeed be capable of realising, by working together and for each other in our economies, gets turned, in the fevered mind of this Austrian aristocrat, into a most fearsome foe, to be quashed and eliminated at all costs.

In Hayek’s mind, democratic aspirations of universal need satisfaction tend inevitably towards totalitarianism, absolute and terrifying lack of freedom. This makes very little sense on its face: indeed, lack of human need satisfaction is arguably the main root cause of massive unfreedom around the world. When people’s human needs are not satisfied, they are not in a position to make or realise any kinds of life plans (see Doyal and Gough’s “A Theory of Human Need,” Amartya Sen & Martha Nussbaum’s work on capabilities and Sen’s book “Development as Freedom,” for starters). So what kind of freedom is Hayek talking about here?

Democracy as lack of freedom for producers.

Hayek, and the other neoliberals, are taking the opposite view of Doyal, Gough, Sen and Nussbaum. They view freedom not from the perspective of human beings who require a decent minimum from the economy, in order to life full lives and realise their human potential. They view freedom from the perspective of producers in the economy, who should be utterly free to act without any social or democratic claims or curbs on their range of action. From this perspective, the perspective of producers, democracy is the high road to “totalitarian” claims, where collective organisation (in this case, seen solely as a centralised state, which itself is reductive and wrong, but understandable given the historical context of Soviet central government) poses an existential risk to the freedom of producers to run the economic show.

Enter market fundamentalism.

Hayek and his neoliberal colleagues now needed another, antidemocratic way, to organise society. They didn’t want democracy, but they wanted some kind of self-maintaining organisation — by which they meant hierarchy. Organisation was supposed to be supplied by the market, and hierarchy by competition within markets. (It’s worth noting that neoliberals in the 1950s did not, although they should have, predict that unfettered markets lead to concentrations in monopolies or cartels. They would arguably disapprove of the vast corporations running our current economies, even though their market-above-democracy policies predictably brought them into being.)

Thus the neoliberal project has always been, and continues to be, antidemocratic at its very core. It is designed to prevent us from collectively debating and deciding how we want our economies, our work, to be organised. And it has succeeded so wildly in the past 40 or so years that the very idea that we could decide together how to work, and how to contribute to each other’s need satisfaction and well-being, seems a distant fever dream. Even though it has never been closer within our reach. Who has been stopping, and is still, stopping us?

Chapter 4. The promoters.

The fossil fuel industry is a long-time promoter, as well as beneficiary, of the neoliberal takeover of our societies.

Let’s face it: the Mont Pélerin Society, as a small clique of higher crust fringe economists and philosophers, would have had a hard time, on their own, taking over the world. But almost from the start, they had powerful and wealthy backers. The intertwined history of the fossil fuel industry and the neoliberal economic-political agenda goes way back. Already in the 1950s, the fossil fuel industry was infiltrating economics teaching in the USA, aiming to “subtly deliver the message that American freedom is the product of extractive capitalism.”

Worse, the dominance of fossil fuel industries in our economies is not a tragic historical accident, but fundamental to the DNA of our economic systems. As Jason Moore, Andreas Malm, Jeremy Walker and Amitav Ghosh have described, global plunder, extraction and exploitation are at the root of the massive profit accumulations that made modern capitalism possible. The fossil fuel industry is not incidental to our economies, it is part of its very structure. And the fossil fuel industry has for decades been painfully aware of its dependence on a cut-throat, producer-dominated economic system, see Naomi Klein’s “This Changes Everything”.

The fossil fuel corporations, and the billionaires they created, in the US and Europe, were convinced of two interconnected ideas. First, that they needed a certain kind of free market capitalism to stay in existence, free of state interference or democratic scrutiny of their operations. Second, that they could gain legitimacy through upholding capitalist economies, by presenting themselves as the grubby Atlas holding up shiny and exponentially growing capitalist wealth. This story is told in far more historic detail and nuance in Jeremy Walker’s epic “More Heat Than Life,” as well as through Amy Westervelt’s extraordinary podcast Drilled.

By the time the 1970s and 1980s rolled around, both the neoliberal intellectuals and their fossil fuel backers had had plenty of time to fall in long term love with each other. The neoliberal thinkers provided the ideas, the fossil fuel industry provided the money to spread those ideas all over the world.

And now, we live in the monstrous offspring of this marriage of conviction and convenience.

Chapter 5. The coordination.

The organisation of the neoliberal takeover is not half-hazard: it is coordinated through think tanks, lobby groups, public relations and legal firms. These in turn are coordinated internationally, for instance via the Atlas Network, which is involved in more than 500 think tanks worldwide.

Neoliberalism at gunpoint …

The first big success of neoliberalism was openly antidemocratic: the 1973 US-backed coup of General Pinochet against the democratically elected government of Salvatore Allende was celebrated as an opportunity by the Mont Pélerin Society. Its luminaries, from Hayek to Milton Friedman, did not hesitate to rush to reshape Chilean society in their ruthless image. The juxtaposition of “liberal” and brutal military dictatorship (Pinochet tortured, murdered and disappeared tens of thousands of leftists, an entire generation) might seem strange to some, but it makes complete sense when we remember that the only freedom of interest to neoliberalism is producer freedom: freedom of corporations to extract, exploit and profit. Allende’s deadly democratic sin, for which he paid the ultimate price, murdered in the Presidential Palace by Pinochet’s men, was the plan to nationalise Chilean copper. How dare a country democratically decide to control its own ressources and wealth. Death, torture and harsh economic policies were the US-backed neoliberal answer to such impudence.

… and at the ballot box.

The next major success of neoliberalism was an even greater prize, when the United Kingdom elected Margaret Thatcher in 1979. No longer would neoliberalism have to be imposed at gunpoint: the Mont Pélerin Society and their industrial backers had found a way to crack the code, and damage democratic societies so badly that they would now choose their own undoing at the ballot box. But how? Two words: think tanks. Jeremy Walker summarises the story in “More Heat Than Life”:

Hayek’s insistence that egalitarian democracy would bring ruin was never likely to win widespread approval by a democratic citizenry on the basis of its reflection upon Hayek’s corpus of ‘scientific’ publications. (…) Hayek understood that protecting the market mechanism from excess democracy would require the engineering of consent, through the intentional construction of an agnotological political machine mass-marketing ‘business propaganda’.

The task of setting up this parallel machinery for mass communication (and the recruitment and training of neoliberal activists) was taken up by the English businessman Anthony Fisher, a devotee of Hayek. In 1955, Fisher founded the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), which later launched the Thatcher revolution from the far right of the Conservative Party. In a letter to Fisher after her 1979 election victory, Margaret Thatcher wrote that the IEA had created ‘the climate of opinion which made our victory possible.’

The stunning success of Thatcher inspired Anthony Fisher to create the Atlas Network: a international federation of think tanks, built on the model of his own Institute for Economic Affairs, who would manufacture ‘the climate of opinion’ enabling neoliberal business propaganda to take over as many countries as possible. This funding of the network is not transparent, but quite a bit of it, if not all, comes from the wealth of extractive industries, first and foremost the fossil fuel industry. The Atlas Network now boasts over 500 affiliates, all over the world (you can learn more and search the ones closest to you here).

Chapter 6. The buildup.

These think tanks train their cadres internally, and promote them to places of influence in policy and communication.

Researchers like Jeremy Walker and reporters with DeSmog have tracked the career pathways of Atlas Network protégés. I am not a specialist here, but in my understanding, the process goes something like this. The think tanks run recruitment courses (summer schools, ‘executive masters’, …) to identify and train their cadres. They employ performance metrics linked to ability to communicate and spread the neoliberal gospel in the public sphere (number of op-eds or letters to the editor published, TV appearances, policy briefs or materials that make it into policy or school curricula …).

They then continue to support their most promising recruits, via think tank positions, but also by trying to place them within media or political parties, with the result that many of the people most vocal and active in right-wing politics have been influenced by Atlas Network ideology, and rely upon it for their professional support network.

Chapter 7. The message.

The Atlas Network think tanks replicate their materials and strategies worldwide. Their poisoning of our public sphere runs the gamut from advocating brutally unequal neoliberal economic policies to promoting climate science denial. They also dabble in divisive culture war topics, on gender (against equal rights for women, queer & trans people), race or migration, for instance.

The topics covered by Atlas Network think tanks are quite diverse, even sometimes contradictory, as a quick visit to their websites and publications reveals. However, they have two core constants. The first is the promotion of business-friendly neoliberal economic policies, disguised and massaged to appear democracy-compatible under Hayek’s mantle of ‘market freedom as the basis for all other freedoms.’ The second is climate denial and delay.

In fact, the Atlas Network think tanks have arguably been the largest conduit and support for promoting climate denial-delay all over the world.

Some Atlas Network think tanks will now have moved on, and present themselves as accepting of climate science, even promoting climate action. It would be best not to be fooled by this superficial change of heart. The core purpose of the Atlas Network is to protect businesses, especially extractive businesses like the fossil fuel industry, who are after all among their most lavish funders and backers, from any kind of democratic government regulation. Even when Atlas Network think tanks pretend to accept the reality of climate change, it will be to delay necessary action via other propaganda, like the promotion of voluntary-only business measures, techno-optimistic dreams of negative carbon technologies, or even the absurd arguments that fossil fuels are necessary for humanity and climate action.

Atlas Network think tanks also dabble in any topics that can cause social division, undermine democratic functioning, and attract more followers to their cause. These include conservative family values, which were a core tenet of Hayek’s planned organisation of society alongside market fundamentalism (see Wendy Brown’s “In the Ruins of Neoliberalism” for more details on this apparent paradox). They also include discussions of feminism, gender & queer rights, and migration. Here it is important to note that neoliberal think tanks will often argue on opposing sides of these issues, some more conservative, some more liberal.

The constant thread, if there is any, will be to push-back against democratically-mandated state intervention. For example, in the image above, we see Swiss neoliberal magazine “Regard Libre” advocating for women’s rights (left) and against gender-queer rights (right). The consistency is not so hard to find: women’s rights are only worthy because they are argued to arise alongside industrial capitalism, i.e. producer-dominated economics. Gender-queer rights are opposed because they are requesting collective, democratically-mandated protection via state recognition.

This is a really important point for pro-democracy advocates, on economy, climate, gender, social justice or any other target of neoliberalism to understand. The communicators of the neoliberal agenda do not care about the fundamental values or reality they are commenting. They don’t care about the specific topic of discussion. At all. They care about the strategic outcome of creating the discussion in the first place. This point is particularly hard for leftists and scientists to understand, since they do care about fundamental values and reality.

The strategic goal of neoliberal communicators is always twofold: to create distrust in democratic, publicly-oriented or funded processes, and to create confusion sufficient to disorient and disable democratic decision-making.

Indeed, the second goal of neoliberal outlets covering all sides of culture war topics, to put it in Steve Bannon’s crude but accurate expression, is to ‘flood the zone with shit.’ This means to amplify a cacophony of divisive topics, in order to undermine reasoned and compassionate collective discussion, and ultimately destroy the capacity for reasoned democratic decision-making.

Chapter 8. The influence.

One core goal of these organisations is to replace university research expertise with their own materials, influencing the influencers, with journalists and teachers identified as prized targets.

The tactic of climate denial organisations to replace university expertise in the public sphere has been amply documented by scholars such as Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway (see their definitive book “Merchants Of Doubt”). This is done via many known tactics. For example, the think tanks produce fake reports, often deceptively formatted to look just like reports from legitimate sources, like the IPCC, to confuse policy-makers and journalists. They present themselves as fake experts, pretending relevant research knowledge where they have none. They organise fake conferences and events, they lobby media editors to give equal coverage to their fake science, and so on and so forth.

What is less known is that a core goal of the Atlas Network is to replace public service expertise, the kind which is publicly funded, in universities or government research institutes, with their own corporate-friendly brand of disinformation. It is worth repeating: the Atlas Network, and its corporate backers, are engaged in a full-on war against universities and public-service knowledge generation and communication. To quote the great Jeremy Walker again (emphasis my own):

Thus the (…) work of the libertarian (…) intellectuals and political insiders seeking to capture the policy planning powers of the state must be complemented with a permanent programme of mass communication to counter and under-mine the sources of the ‘wrong’ sets of beliefs — public universities, public servants, public broadcasters, public scientific institutes — and to coax, confuse or intimidate the citizenry into accepting their submission to a market order in which all public knowledge, assets and services are, in the long game, to be fully privatised.

The Atlas Network’s war on public-service information (defined as any information coming from sources that are not directly funded by industry) should be understood as a core part of its war on democracy. Democracy, self-rule by the people, is impossible without a sound basis of information upon which to make decisions. By undermining and replacing public-interest experts in the communicative sphere, the Atlas Network’s organisations seek to deprive us of the foundations that democratic decision-making processes rely upon: a good understanding of reality itself.

This is not to say that academics, public-sector broadcasters or civil servants are universally correct or above reproach. They can be biased and get things wrong, which is normal, and only to be expected. Indeed, each Atlas Network think tank relies on some ideologically-aligned university professor (usually economists or philosophers, for some reason?) to be on their advisory board, and teach at their summer school or executive masters. However, unlike the industry-paid, snake-oil-salesmen of the Atlas Network, public-sector experts are ultimately accountable to the public: they are publicly, transparently, accountable for their errors, because of their public-sector roles.

No such rules of accountability apply to Atlas think tanks. Their goal is to flood the zone with pro-industry, pro-wealth, anti-democratic shit, reality be damned, until any possibility of reality-based democratic decision making is a remote dream. And in many places, in many communities, they have already succeeded.

Chapter 9. The implication.

To counter such centralised and coordinated actors, the climate movement (and indeed all movements attacked by neoliberalism) should change radically, both in orientation and strategy.

I first heard of the Atlas Network last year, despite having been active in social justice movements pretty much my whole life, and trying to understand why we kept losing (or at the very least winning far too slowly) my whole life. I cannot express how deeply unsettling it is to be a university researcher, an international expert on climate social science, and recognise so recently, so very late in the game, what we are up against. I believe the awareness and knowledge brought by recent research, cited in this essay, should cause us to rethink how we organise to counter it. I am not a political or communication strategist, so these are just some thoughts for starters. This is work we must do, as swiftly as possible, together.

- We need to communicate about what we are up against. The climate strike generation needs to be aware that their societies failed to react, not because democracy is incompatible with climate justice, but because our democracies have been attacked for decades by the very same actors destroying the climate. We need to spread awareness and knowledge of the Atlas Network, its funders and allies, so our movements understand who we really are up against.

- We need to research and keep track of Atlas Network affiliate actors and outlets (as well as other dark money orgs). This is huge work, and because of recent attention, they are starting to cover their tracks, at least on the internet. If you are a researcher, join the Climate Social Science Network, and start collaborating to gather as much information on the shadowy network as possible. Scrape internet archives, ask for funding records and formal organisation records. And publish your results.

- We need to band together as pro-democracy, pro-equality, pro-human rights, pro-social justice movements. We might not have full awareness of each other’s issues (or even be convinced of their validity), but we are facing the same centralised enemy. At least at the strategic level, we need to share information about their operations, and strategise on how best to counter them.

- We need to counter the neoliberal takeover of our world not issue by issue, but at a strategic level. Remember Chapter 7, and the two goals of neoliberal communication? Debating them on the content is a long-term losing strategy, see decades of climate denial. Sure, we should be doing debunking on a factual level, but we should focus the main part of our energy on the goal of the disinformation: collective inaction, leaving the field open for rule of industry and billionaires. They are trying to stop democratic capacity for action, and we need to debate them on this field, where they are weakest.

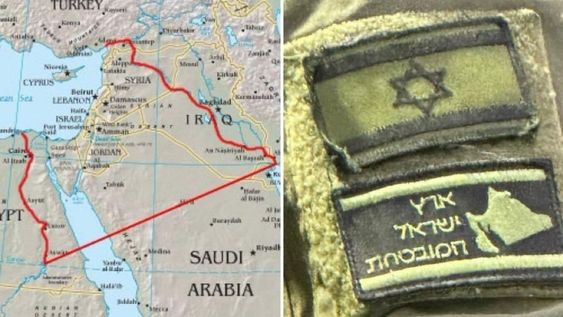

- Movement activism, protest and civil disobedience cannot be victorious in this context. This is the hardest one to write, because it is where so many of us have focused our energy, for decades. I am not denying the huge victories of the climate strikes or Extinction Rebellion in raising the topic of the climate emergency to the fore, or the successes of Black Lives Matter and Palestinian liberation movements (the most important of our times) in raising the uncompromising demand for universal freedom, emancipation and human rights. But let’s face it: decades into an accelerating climate crisis, with white supremacy and Palestinian genocide triumphing, these movements are not winning. My argument here is that this is because their targets and tactics did not (and still do not) take into account the deliberate takeover of our societies by neoliberal actors, orchestrated internationally by the Atlas Network. The horrifying fact is that we are not citizens in democracies, addressing our governments to redress injustice. If that were the case, we would have won a long time ago. We are disenfranchised people, facing governments taken over by industry actors, who welcome inequality and suffering as part of their ideology and business models. They were never going to respond to legitimate grievances, positive proposals, or democratic demands of any shape or form — on principle. The question then becomes: what can we do that would have a better chance of working?

- Use their own tools against them, but more effectively. Of course, we don’t have the funding levels of the billionaire-bankrolled Atlas Network, but we have lots of advantages: reality is on our side, as well as immensely popular values of democracy and rights for all. And we have research capacity as well as real popular movements. One thing we need to do is counter them at their own game: producing op-eds, newspaper letters, TV appearances, school curriculum oriented materials, and so on, and so forth. We have to flood the zone with good stuff. This means doing things differently: training activists and academics to become excellent, prolific public communicators, including understanding appearances and discourses that are most appealing to vast masses of undecided. Perhaps it means wearing suits & ties, perhaps it means speaking to the languages and values of different social classes, and integrating them fully into our movements. After all, if a bunch of neoliberal anti-democracy con-men could take over the world by looking slick on TV, just think of what we could do for a reality-based prosperity-for-all pro-democracy agenda with a nicer haircut and some ironed clothes. All of this is well outside of my comfort zone (especially the haircut and the ironing, lol), but it’s essential. And remember to communicate at the strategic level!

- Bring the fight off the streets. Don’t get me wrong: mass protest, and even civil disobedience, are absolutely necessary to keep spurring action. But we need to take our goals and messages to many other arenas, and bring the battle against neoliberal influence into meeting rooms ranging from municipal deliberations to corporate board-rooms. This is easier said than done, of course, and many will argue that we have been doing just that, with climate activists disrupting shareholder meetings and so on. However, I am talking not just about disruption here: I am talking about exposing & countering the neoliberal agenda wherever it is taking hold, and building internal strength to resist it. We are only as strong as our collective organisation, and we need to insist on our capacity to self-organise, rooted in reality-based analysis, to every institution in our societies.

- Start believing in humans again. Quite simply, the fault is not in ourselves, but in the wild success of the organisational tactics of a few destructive and wealthy ideologues. The state & trajectory of our current societies do not reflect the aspirations, potential or desires of the vast majority of our fellow humans. It is true the neoliberal revolution did its worst to reshape humanity in its image: isolated, selfish, cut-throat competitive. But homo-neoliberal is not, and was never who we are. More and more research is coming to the fore, showing humans to be among the most cooperative and communicative animals. Indigenous scholars remind us that human societies creating cultures of long-term equity and stability within their environment have existed for millennia before capitalism. Graeber and Wengrow “Dawn of Everything” demonstrated clearly how suited humans are to inventing and reinventing governance systems, how capable (even desirous) we are of democratic and equitable social arrangements, even if these are always threatened by power grabs. This means that the frequently-found misanthropy on the left and in environmental circles is utterly unfounded, and totally counter-productive. It is time to put forward the vision of homo (or better, femina!) oikologica, the humans democratically taking care of each other and their environment (drawing on the greek concept of oikos: household, economy and environment). This is who we were, and who we can become again. It is time to encourage ourselves and our fellow humans to believe in our collective capacity to change things, work & care for each other’s prosperity, and kick the neoliberal monsters devouring our societies out of our history.

- Turn anger and knowledge into revolution. The hour is late, both in terms of the triumph of neoliberal economics and its tag-along fascism, the acceleration of irreversible climate change. The betrayal of the promise and potential of our societies is immense. But there are two emotions that can energise even the most depressed and defeated: anger & hope. There has never been more objective reason for anger, learning this new evidence about the destruction of our societies and our worlds. And there has never been more objective reason for hope, given the new possibilities for alternative energy production, away from fossil fuels, and sufficient and efficient ways of using it. For the first time perhaps ever, ecologically safe universal human prosperity is within reach. There is a lot to be angry about, and even more to fight for. Onwards.

Chapter 10. The direction.

Democracy, the fearsome foe of neoliberalism, should be at the heart of our new direction.

The biggest revelation from all this for me was that neoliberalism was born of a fundamental fear of democracy, and desire to eradicate it. Markets as the preferred hierarchical organisation of society were secondary to the necessity to destroy democracy. In Hayek’s mind, democracy would lead immediately to collective discussion & organisation, with the outcome of shared decisions to realise human potential through universal need satisfaction. And for Hayek, this was unacceptable, because it would be an imposition upon producers, the wealthy owners of capital. For Hayek, democratic demands for universal need satisfaction translated automatically to tyrannical state authoritarianism, where a faceless, nameless bureaucracy would impose production & consumption quotas, and freedom of all kinds would be eliminated. Of course, no one particularly likes tyrannical state bureaucracies (except of course when they happen to improve and save your life through welfare programs, from education to health to housing, which happens quite frequently, truth be told). But Hayek was wrong: democracy does not mean tyrannical state centralisation and overreach. At least not automatically. Democracy, in the fundamental sense of the term, means self-organisation and self-determination. It means autonomy and emancipation. It means people coming together within their societies to make their conditions better and safer. In short, democracy is the decision-making process for organising generalised mutual aid.

Rather than the faceless, nameless central state bureaucracies dreaded by Hayek, we can advocate for generalised democracy, throughout our communities and economies. Part of our work as citizens should be in the organisation of the life of our communities. Rather than allow nameless faceless mega corporations to make predatory & destructive decisions, we should work together and trust each other to come up with better plans. This is true for every organisation, public or private, at any scale. We have a hugely diverse palette of democratic structures and processes to draw upon, from citizen assemblies to worker-user cooperatives. Researchers and practitioners have created fantastic toolkits, helping us to understand the pitfalls and strengths of these. We should reapropriate our ability to learn and enact diverse forms of democratic governance, learning from successes and mistakes alike. As we learn how to work together and create different structures through our decision-making, we will learn to threaten the neoliberal hegemons and their power grip on our societies, including the capture and corruption of our states.

Democratic decision-making can only happen under two core conditions. The first is the respect of vulnerable minorities (of all kinds, via disability, indigenous, gender, work, migration, age etc status), and their specific perspectives and needs. The second is the acknowledgement of scientific reality. This second one means that democratic decision-making should always work hand in hand with public service research and information. This is not to say that scientists should determine decisions, but rather that research should be oriented to support democratic deliberation and decision-making, and that citizens should be trained to understand the domains of validity of research results. The consideration of scientific results, alongside the fostering of a culture of care and reciprocal work, is what will enable our decisions to bring us back within planetary boundaries, while protecting the most vulnerable from the harms already upon us.

That was a rather technical point to end this essay on, and sadly it wasn’t short, as promised. It ended up being quite long. I hope it helps and inspires you, and your organisations, to turn your attention towards the very real monsters burning up our world, and create the new democracy to build better and safer societies.

Chapter 11: Epilogue.

Important stuff that deserves its own treatment.

There are a bunch of things I didn’t get to in this essay that deserve their own treatment in relation to neoliberalism and its influence on our economies and politics.

- The rise of fascism. Neoliberal ideologues align perfectly with brutal far-right dictatorships, see Pinochet for just one example. But even in democracies, neoliberal policies constribute to the rise, even triumph, of far-right fascist movements. As the great Karl Polanyi describes in his epic economic history “The Great Transformation,” the rise of Nazism was greatly aided by economic crisis and insecurity in Germany after WWI. Neoliberal policies have much the same effect: they make the poor and middle class poorer, of course, but they also fragilise welfare safety nets, which is after all one of their main goals. The resulting economic insecurity and generalised stress, something Ajay Singh Chaudhary characterises as ‘exhaustion’ creates fertile ground for the growth of the easy false problem, false solution proposals of fascism. The results are clear to see, from Europe to Americas. Even the rise of the oligarchs and Putin in Russia is best understood as the logical historical outcome of the harsh neoliberal policies imposed by the West after the fall of the Soviet Union.

- A full critique of limited democracy. This essay did not go into any detail regarding the limitations of representative liberal democracy, which are legion. Suffice it to say that some democracy is better than none, and democratic means should always be used to their fullest by popular movements. However, we need broader and deeper democratic practices throughout our societies, and especially we need to bring democratic decision-making into our economies, into practices of production and consumption.

- State authoritarianism, from Saudi Arabia to China. The topics treated in this essay are most relevant to the recent history of Europe, the Americas and parts of Asia. In other parts of the world, state authoritarianism dominates, and democracy is not just limited, but non-existent. These areas are massive, and also some of the most populous and fossil-fuel rich in the world. Any kind of program for human equality, democracy and climate action has to consider these seriously as well. In some ways, these countries, with their state-run fossil fuel enterprises, are surprisingly compatible with the neoliberal vision. In the case of state-run fossil fuel industries, in fossil-fuel rich countries, it is quite often the case that the industry runs the state, rather than the other way around. These countries can thus be seen as the extreme case of producer freedom: just for the biggest, baddest producers around. The fossil fuel companies and their oligarch billionaires are not suffering under the authoritarian rule of the state: they are the state. Sure, market freedom and competition are absent, but that is really so different from the current era of neoliberalism, dominated by a few massive conglomerates which are most adept at capturing state policy and eliminating competition? In any case, the consideration of authoritarian states has to be done carefully and accurately. One sure way to fragilise the power of these governments is to drastically reduce dependency on fossil fuels and unnecessary consumption, as well as building up local renewable energy production and manufacturing-recycling capacity. So in resource use or climate mitigation terms, there is no contradiction. In geopolitical terms, preventing these countries from imposing fossil fuel dependency on Africa, their next identified prize, will require massive solidarity with African scholars and activists.

- Transhumanism, e/acc, long-termism & Co. The tech billionaires alongside some academic collaborators are developing a new ideology, and enabling its spread at the highest levels of government and industry. I am not an expert: Emile Torres, Alice Crary and a few others are. This ideology promotes the development of information technologies above all other human endeavours. In its most extreme version, this ideology argues that technological development, fueled by economic growth, is worth completely destroying planet Earth, since the technological progress will somehow spread to space. The deaths of billions of human beings are justified for a future of technological space prosperity. Indeed, the technology will come to replace human beings, since according to transhumanism, the destiny of humanity is not a stable and prosperous life on planet Earth, but simply a stepping stone to more evolved technical forms of intelligence. This sounds bonkers, and it should. No serious astrophysist or biologist or anyone, really, takes it seriously. Transhumanism and e-acc can be understood as neoliberalism on Silicon Valley steroids: all freedom, ressources and range of action for tech producers, none for humanity or even life on the planet. It is extremely dangerous, and should be studied and opposed as such.

- Decolonisation and the recognition of indigenous social organisation and scholarship. The rise of the economic thinking, structures and fortunes accompanying the formation of neoliberalism all have their roots in colonial domination and exploitation. Jeremy Walker’s “More Heat Than Life” does a great job of covering some of this history, so does Jason Moore’s work. Moreover, the welfare states that neoliberalism set out to destroy were arguably also only possible, and built upon, colonial theft. Colonial practices of exploitation and unequal exchange, in human, ecological and economic terms, continue to this day. The question of which kinds of geopolitical, economic and social organisation would undo this centuries-long crime should be a core concern of democratic societies, as well as the question of preventing the rise of predatory & violent empires, whether dominated by the US, Europe, Russia or China. Reparations for colonial oppression and centering of indigenous knowledges will both be central elements here, but this discussion requires far more expansive treatment as well.

- Specific action plans for climate, biodiversity, equality, prosperity. Since this text was devoted to mapping out the history of the opposition, it did not spend much time on the practical world we need to be working towards. In brief, we now have technologies which would enable us to live well within planetary boundaries, but only if we invest our work in the most efficient ways of using resources (insulated housing, efficient household appliances, public transit & biking, plant-based diets, etc) AND sufficient consumption levels. Sufficiency means no deprivation, but also no major excess. If we move our economies and societies towards these measures, we could easily, within a couple of decades or even less, achieve prosperity and, yes, freedom, for all, within planetary boundaries, realising what George Monbiot has called ‘private frugality and public luxury.’ We could have beautiful, lush, safe living spaces, lower working time, more time for family, friends and community care, with greater autonomy and emancipation. This is possible, and it is certainly worth working for.

Main references (used throughout)

Wendy Brown (2019). In the ruins of neoliberalism: The rise of antidemocratic politics in the West. Columbia University Press.

Jeremy Walker. “More Heat than Life: The Tangled Roots of Ecology, Energy, and Economics”. 2020. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-981-15-3936-7

Amy Westervelt’s Drilled Podcast https://drilled.media/podcasts/drilled

George Monbiot and Peter Hutchison (2024) “The Invisible Doctrine”

I haven’t read these but Céline Keller says I really should

Quinn Slobodian (2018). Globalists: The end of empire and the birth of neoliberalism. Harvard University Press. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.4159/9780674919808/html

Quinn Slobodian (2023). Crack-up capitalism: Market radicals and the dream of a world without democracy. Random House. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250753892/crackupcapitalism

Comments are closed.