We can say with great certainty that we have only seen the beginning of the climate crisis. The future will be worse. Far worse.

By Tore Furevik, Director of Nansen Environmental and Remote Sensing Center, first published in Norwegian on NRK.no on July 31. 2023.

It is impossible to predict how high the temperature will reach until we stabilize it. Ideally, the trend should be reversed because the chronicler writes that the climate is far from equilibrium even if the temperature stops rising.

Our emissions of greenhouse gases lead to an increasingly warmer climate. The heat waves, fires, and floods we have seen in recent years are not the new normal. It is the situation today. The future will be far worse.

Last year’s summer was the hottest ever recorded in Europe, almost half a degree above the record from the previous year. Heat waves, drought, and fires in Europe, North America, and China characterized the summer.

It is estimated that the heat waves led to over 60,000 extra deaths in Europe, and the annual global costs of heat waves as a result of man-made climate change are estimated to be 1000 billion dollars.

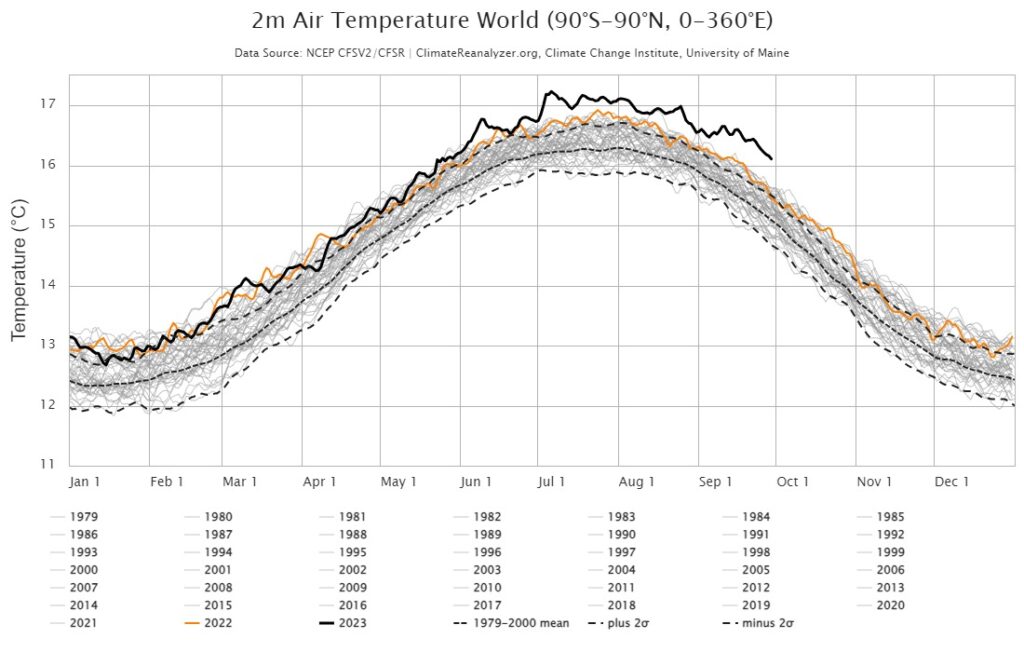

Those who had hoped that last year was the exception have been emphatically disappointed. It has gone from bad to worse. We have put several weeks behind us of the highest average temperatures ever measured on the planet, probably the highest in 125,000 years.

The sea surface has been record warm since March, and with an El Niño building up in the Pacific Ocean, there is every reason to believe that the heat will continue throughout the autumn and winter.

We know the result of all this heat. North America and China have had temperatures above 50 degrees, while Europe has settled for 48 degrees.

Tourists and permanent residents have had to escape from forest fires on Greek and Italian islands, and many places on the mainland on the north and south sides of the Mediterranean were burning and are still burning. According to the EU’s monitoring program Copernicus, the fire risk in the entire region is extreme or very extreme.

Warmer air can hold more moisture. A simple rule of thumb is a doubling for every 10 degrees. Heat waves, therefore, lead to more evaporation and drying of the soil but also to extreme amounts of precipitation and strong gusts of wind when the conditions are right for it. We see a growing tendency towards this here in Norway as well, although we are unlikely to see hail the size of tennis balls and wind gusts of over 200 km/h as northern Italy and Switzerland have experienced recently.

Perhaps the most serious consequences are likely to occur in the sea, where there are also heat waves. In parts of the Mediterranean, temperatures above 30 degrees are reported, and in the waters around Florida, up to 38 degrees [about 100 degrees Fahrenheit or the temperature most people would choose for a hot bathtub]. It is too early to say what effects this will have, but we know from the past that marine heat waves are a major threat to coral reefs and entire ecosystems in the sea.

A recent research group behind World Weather Attribution shows that this summer’s heat waves in North America and Europe would not have been possible without man-made global warming and that the heat wave that has hit China has been made 50 times more likely. As long as we continue to emit greenhouse gases, the warming will continue, and the consequences will worsen.

Our use of energy and land increases the amount of carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and other greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This causes the Earth to absorb more energy from the sun than it sends back into space.

Calculations made by NASA show that net added energy has more than doubled in recent decades. Almost 90 percent of the extra energy ends up in the sea, where one can measure that the heat content increases with each passing year.

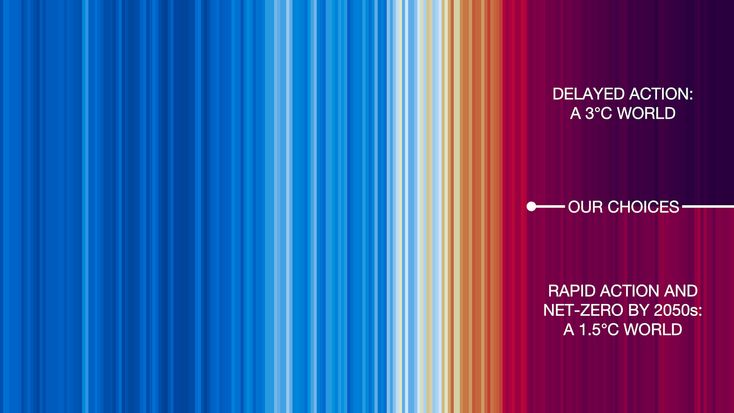

In the Paris Agreement from 2015, almost all the world’s countries have signed up to limit global warming to well below 2 °C and to strive to limit it to 1.5 °C, compared to pre-industrial times. If this goal is to be achieved, it will require emissions to go towards zero within just a few decades.

With the exception of the COVID year 2020, emissions have increased every single year since 2015, and there is very little indication that the trend can be reversed quickly enough to avoid 1.5°C or 2°C warming.

Nevertheless, positive things are happening around us. The world’s three largest economies, the US, China, and Europe, have all been hit by heat waves and droughts in recent years.

At the same time, they have put themselves in the driver’s seat when it comes to ambitious climate targets and measures to accelerate the transition to a renewable society. The price of solar and wind energy continues to fall as the pace of development increases, and there is reason to believe that we will soon have seen the emission peak in terms of greenhouse gases.

It is impossible to predict how high the temperature will reach until we stabilize it. Ideally, the trend should be reversed because the climate is far from equilibrium even if the temperature stops rising. Many things can get worse for a long time to come.

This applies, among other things, to the melting of the large ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland, warming of the sea, sea level rise, drying up of groundwater, desertification, and loss of biological diversity.

We can only say with great certainty that we have only seen the beginning of the climate crisis and that it is more urgent than ever to bring about a more sustainable social development.

This is the challenge for our politicians, who will soon be back from a well-deserved summer holiday.

Comments are closed.