The UK government pursues laws and policies with little regard for their impact on human rights. The government cut social security affecting millions despite clear warnings it would increase food insecurity, debt, and homelessness. The response to increased migrant boat crossings across the English Channel was draft legislation and proposed pushbacks at odds with refugee and human rights law.

A landmark parliamentary oversight report found that existing social, economic, and health inequalities and failures in the UK government’s Covid-19 pandemic response led to disproportionately high death rates among people in institutions such as care homes, people with learning disabilities, and autism, and Black and ethnic minority people. The government again failed to take meaningful steps to tackle institutional racism. Although the UK government worked in coalition with partners to call out human rights abuses on key issues, when weighed against other interests, it did not always prioritize human rights in its foreign policy agenda.

The Rule of Law and Human Rights

In March, the government published an independent review of the power of courts to hold the executive to account. It recommended only modest changes to judicial review and while the legal profession remains cautious about the government’s intentions, its proposals for legislative change are more limited than initially feared.

A separate review into the Human Rights Act was expected to publish its findings in late 2021. Although the government says it intends to remain a party to the European Convention on Human Rights, the ruling Conservative party’s track record of hostility to the act and comments from the justice minister raised concerns that the review could be used to water down rights and other legal protections.

Asylum and Migration

The UK ratcheted up rhetoric and efforts to restrict arrivals of migrants and people seeking asylum crossing the English Channel from France in small boats, raising concerns for the rights and safety of people making the dangerous journey. By the end of September, an estimated 17,085 people had crossed the Channel in this way during 2021. After announcing plans to push back such boats into French territorial waters in September, UK border enforcement guards were filmed conducting drills in which they appeared to practice potentially dangerous techniques such as pushing and ramming boats with jet skis.

Measures proposed in a draft migration law in July would undermine international refugee and human rights obligations, including further criminalizing people seeking asylum (increasing the sentence for “illegal entry,” penalizing people based on their mode of arrival, and broadening the definition of “assisting unlawful immigration”); allowing offshore processing and detention of asylum-seekers; creating a discriminatory, two-tier system of protection based on how a person sought safety in the UK; increasing maritime pushback powers; and providing immunity to border guards from civil or criminal proceedings arising from engaging in maritime pushbacks.

The Nationality and Borders Bill was widely criticized by the UN refugee agency and domestic civil society groups. At the time of writing, the bill was being examined by the parliamentary human rights committee.

UK authorities pledged to resettle 5,000 Afghan refugees in 2021 and a further 15,000 within five years following the Taliban’s seizure of power and the NATO troop withdrawal, in addition to facilitating the evacuation of nationals and Afghans who are eligible under the UK’s Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy.

A Home Office scheme, set up in 2019 to compensate a group of Black British citizens, known as the “Windrush generation,” wrongly threatened with deportation or deported from the UK, continued its work but faced criticism from victims and a parliamentary oversight committee for being too slow. Two men, aged 55 and 67, from the Windrush generation began litigation in September seeking greater transparency on the process for expediting urgent claims.

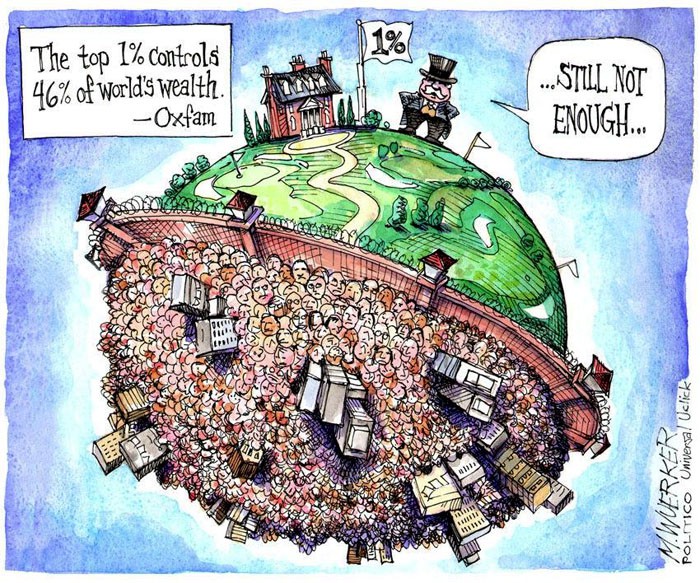

Rights to Social Security, Adequate Standard of Living

In October, the government cut up to £1,040 (US$1,439) per year from social security support to people on the Universal Credit system, despite widespread warnings that doing so would further exacerbate poverty. The government argued it was ending a temporary Covid-19 relief measure, but failed to disclose its impact assessment of the cut on approximately 6 million people. Domestic civil society groups and frontline professionals predicted the step would increase food insecurity, debt, and homelessness and harm physical and mental health. The UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty warned that the cut did not comply with the UK’s socio-economic rights obligations.

Rights groups raised concerns about people with disabilities receiving inadequate social security support, including an estimated 2 million people, many of them people with disabilities or long-term health conditions, on “legacy” benefits which predated the Universal Credit system, who never received the additional £1,040 per year.

Right to Food

Official data published in March, but collected prior to the pandemic, showed 43 percent of households receiving Universal Credit were experiencing food insecurity. The data showed the disproportionate impact of food insecurity on families headed by a single adult (predominantly women) or a Black person, families living on less than £200 ($276) per week, and people with disabilities.

Demand for food banks grew as the number of Universal Credit claimants increased to 6 million by March, doubling since the onset of the pandemic.

The country’s largest food bank network reported that it had given out 2.5 million emergency food aid packages between April 2020 and March 2021, up 33 percent compared to the prior year, and its data showed lack of income and inadequate social security support as the main drivers.

In July, the National Food Strategy, an independent review into the country’s food systems, recommended removing obstacles for families seeking free school meals for children; ensuring long-term food provision for children during school vacations; and extending an existing food subsidy program for pregnant people and families with young children.

Children’s Rights

In March, Scotland’s parliament passed a law incorporating the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child into Scottish law. In October, the UK Supreme Court ruled, following a constitutional challenge by the UK government, that the Scottish legislature had acted beyond its powers and asked for the legislation to be revised.

In July, the Supreme Court rejected a human rights challenge to the “two-child limit” welfare policy, which caps payments to families with more than two children born after April 2017. Although the court accepted that the policy disproportionately affected women and children, it found it objectively justifiable. Official statistics published later that month estimated that the policy affected 1.1 million children in Great Britain.

In an important case about access to health care for trans young people, the Court of Appeal affirmed in September that children under 16 are capable of consent to treatment and that clinicians rather than courts can determine if they have exercised it.

The number of people living in “temporary accommodation” or housing or hostel places provided by local government for homeless families increased by 75 percent over the prior decade. Official data published in September estimated that 30,700 households with children were living in temporary accommodation in London alone and growing up in substandard conditions, due to a lack of suitable affordable permanent alternatives. Children faced a severe impact on their rights to an adequate standard of living and education.

Abortion

In July, the UK government, using new powers, directed Northern Ireland authorities to fund and make available abortion services by March 2022. Access to abortion in Northern Ireland is limited, with one medical trust unwilling to perform abortions and others underfunded. In October, the Northern Ireland High Court ruled that the UK government had failed to act “expeditiously” to ensure access to abortion services.

Gender-Based Violence

The Domestic Abuse Act, which entered into force in April, introduced positive changes, including a statutory definition of “domestic abuse,” new offenses, better protection in family courts, and enhanced duties for local authorities to support survivors. However, women’s rights organizations criticized the bill’s failure to protect migrant women adequately. The UK has not ratified the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (known as the Istanbul Convention), which requires states to ensure such protection. At the time of writing, the UK had also not ratified the Violence and Harassment at Work Convention of the International Labour Organization (ILO).

Following the government-commissioned Rape Review’s report in June, ministers apologized for failing rape victims and committed to reversing a downward trend in rape prosecutions and convictions despite increased reports to police. In July, official criminal justice statistics showed a further drop in proportions of suspects charged with rape or domestic abuse during 2020-21, despite a documented increase in domestic violence during the Covid-19 lockdowns.

At the time of writing, 112 women had been killed in the UK in 2021, according to Counting Dead Women. They include men killing women walking in public such as Sabina Nessa killed by a man five minutes from her home in September, and Sarah Everard, who was kidnapped, raped, and killed by a serving police officer in March. Everard’s killing prompted protests and widespread concern that police are not serious about tackling violence against women, including by police officers. Revelations during the prosecution of Everard’s killer in addition to reports from former and serving female police officers raised alarms about ongoing sexism and misogyny within the police force.

In October, an employment tribunal in Scotland found that a female firearms officer had been victimized by sexist workplace culture. Women’s rights activists oppose a policing bill that would not address police failures to tackle violence against women and would curb other freedoms, including the freedom to protest.

In September, the Investigatory Powers Tribunal ruled that police had violated multiple human rights of an environmental activist when a male police officer formed an intimate relationship with her between 2003 and 2005 as part of undercover policing practice. The activist, Kate Wilson, is one of several women who have come forward to report institutionally sexist practices in covert policing. A broader public inquiry into undercover policing remains ongoing and is expected to report back in 2023.

Racial and Ethnic Discrimination

A government-appointed commission to review racial disparities received widespread criticism for finding in April that “institutional racism” had largely disappeared. The Windrush scandal, multiple government-commissioned reports, and official data indicated that, to the contrary, racial and ethnic disparities continue, including in employment, criminal justice, and health.

A draft policing law proposed in July drew widespread criticism, including for planned curbs to protest rights, and the likely impacts of wider police search powers on people from ethnic minorities, especially Black people, and wider anti-trespass powers on Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller people living in informal settlements. The government’s equalities impact assessment acknowledged the disproportionate discriminatory impact of the search and trespass powers but argued that such discrimination was indirect and justifiable.

Impunity for Conflict-Related Abuses

In April, the Overseas Operations Act became law, creating a presumption against prosecution for some crimes committed by UK forces overseas. Following widespread criticism, the government removed the worst provisions of the law, which would have effectively created immunity for genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes.

In July, the government proposed a statute of limitations on prosecutions relating to over three decades of political violence in Northern Ireland. Family members of people killed by security forces, and the region’s lawyers’ association, opposed the plan, seeing it as a de facto amnesty. In September, the Council of Europe’s human rights commissioner criticized the proposals.

Grenfell Tower Fire and Right to Safe Housing

An inquiry into the June 2017 Grenfell Tower fire that killed 71 people continued, hearing evidence of a catalog of failures, including listening to the concerns of residents, many of migrant or ethnic minority background, whose warnings of fire risk were ignored. In February, the government announced a £3.5 billion ($4.85 billion) fund for low-interest loans to apartment owners in private high-rise buildings needing to replace dangerous cladding similar to that in Grenfell. Fire safety legislation passed in April began translating some of the inquiry’s first recommendations into law.

Terrorism and Counterterrorism

In February, in a case relating to withdrawing citizenship from UK nationals who travel to join armed groups abroad, the Supreme Court ruled that Shamima Begum did not have the right to return to the UK from northeast Syria to participate in court proceedings to challenge the UK’s revocation of her citizenship after she joined the extremist armed group Islamic State (also known as ISIS) in Syria. The citizenship revocation left Begum, who joined ISIS when she was a child, effectively stateless. More than 50 UK women and children previously linked to armed groups remain in camps in northeast Syria.

Climate Policy and Impacts

The United Kingdom is among the top 20 emitters of the greenhouse gases responsible for the climate crisis taking a growing toll on human rights around the globe. Prior to hosting the 2021 UN climate conference in October, it embraced ambitious emissions reduction targets—first through its national climate plan commitment to reduce emissions by 68 percent by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and in June 2021 through a legislated target to reach a 78 percent reduction by 2035 compared to 1990 levels. According to the Climate Action Tracker, the UK’s 2030 target is aligned with the country’s aim to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, and with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. However, the UK is not on track to fulfill these commitments. Indeed, the UK continues to expand fossil fuel production and channels billions in domestic support to fossil fuels despite its commitment to phase out fossil fuel subsidies.

According to the UK’s climate advisory body, the UK’s climate adaptation efforts have not kept pace with the country’s increasing climate risks, including risks of heat-related health impacts, and climate impacts on infrastructure and food security.

In November, a regulation was adopted to restrict imports of agricultural commodities linked to illegal deforestation or the violations of laws pertaining to the ownership or use of land, as defined by the commodity’s country of origin laws. Many of the essential aspects of the legislation, including the enforcement mechanisms and the commodities that are covered, are to be defined by the secretary of state. The government should have shown greater ambition by defining land rights along with international human rights standards.

Foreign Policy

Since its departure from the European Union, the UK has proven its commitment to some key issues related to working closely with partners to call out and pressure certain states that fail to comply with their human rights obligations. However, when weighed against other interests, the UK did not always prioritize human rights in its foreign policy agenda.

The Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office continued to work to develop an Open Societies Strategy. The strategy, part of the work of a new Open Societies and Human Rights Directorate, represents an important potential opportunity to mainstream and prioritize human rights in UK foreign policy.

However, during 2021, the government significantly cut its foreign aid budget, which supports human rights and civil society globally. There were also signs that the UK would prioritize trade over human rights, including reinstating trade preferences for Cambodia that had been withdrawn by the EU for human rights violations, while at the same time opposing effective parliamentary oversight over any new trade deals.

The UK refused to impose mandatory human rights due diligence on UK businesses and continued to license the export of billions of pounds of arms sales to countries such as Saudi Arabia where they are used in the war in Yemen.

The UK took more concrete steps in response to China’s ongoing human rights violations in Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Tibet. The UK imposed human rights sanctions on Chinese officials (to date only in relation to Xinjiang), supported a joint statement at the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC), and made a further statement that called for an HRC resolution on China—the first time a state has publicly called for this.

The UK took robust action in response to the military coup and related human rights violations in Myanmar. It imposed sanctions on a number of key individuals and entities and suspended all support involving the government directly or indirectly other than for exceptional humanitarian reasons. However, as a penholder on Myanmar at the UN Security Council, the UK failed to push for any meaningful action. The UK co-led a Special Session of the HRC in February in response to the coup, and while the text was weakened to maintain consensus, it supported a relatively strong resolution at the ensuing March HRC session. As president of the G7, the UK led three strongly worded G7 statements on Myanmar.

The UK played a largely positive role at the HRC with some stark exceptions. The UK sponsored and successfully advocated for the renewal and strengthening of a resolution to advance accountability in Sri Lanka, supported the creation of a special rapporteur on climate change and Afghanistan, and joined statements denouncing widespread human rights violations by Egypt, Russia, and China.

The UK also voted in favor of the resolution, which recognizes the right to a safe, clean, healthy, and sustainable environment. However, it voted against a commission of inquiry into the root causes of recurrent tensions, instability, and protraction of conflict in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and Israel, despite unanimously supporting every HRC resolution creating a UN inquiry over the past decade (except those on Israel/Palestine).

This was coupled with the publication in April of a letter by the prime minister to an internal party group, which asserted that the UK strongly opposed the International Criminal Court’s Palestine Investigation and suggested that the UK would seek to interfere with the independence of the court to further this end. The UK also sought to weaken an African Group resolution on systemic racism and police violence, expressing concern at references to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) transformative agenda to combat structural racism, as well as to reparations and the legacies of colonialism. Ultimately the UK supported the resolution.

The prime minister appointed a special envoy on the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people, tasked with championing LGBT equality at home and abroad.

1 Comment

Pingback: Rights are anti-democratic in nature - that's why we have them, as Counterpower - Bergensia