by agreement with the author @NGOSceptic

originally published at Karma Colonialism

It was coffee break at the annual conference for the NGO I worked for. My colleague M– and I, both from Kenya, were talking as we took in the beach at the seaside resort where we were staying. The annual conference brings together program staff from different countries and our donors. During this time of the year, the program teams review the past year, share experiences among different country programs, and plan for the new year. A little away from us, talking animatedly amongst themselves, was a group of colleagues and donor representatives. So, there was the country director of the host country where we were congregating this year, the program Director for our program, some other program officers from our head office, the program officer from our donor, and the donor program officer’s boss. They were in deep discussion about what needed to be done. What did the group have in common? They were all foreigners, actually ‘Mzungu’ (White person in Kiswahili) from various parts of the globe: the USA, Sweden, Kenya, and England.

I looked at M– and realized that she was also looking at them too. ‘M–, what is wrong with that picture?’ I asked, pointing at the group, African style with my lips so that it is not so obvious that we are referring to them in case anyone was watching. M– looked back at me with a knowing look. She replied, ‘I know, I know S–, foreigners discussing how to solve our problems.’ ‘I did not realize that it had occurred to you too,’ I responded. ‘It occurred to me many years ago just how we who are affected by the challenges of development seem to be excluded from high-level solutions of our challenges.’ ‘That is the reality so get used to it!’ she added. Discussion closed!

That is reality, the sad reality. Perhaps M– was right. I should just accept it, do my bit, earn a living, and advance my career. But something bothers me and I cannot help but wonder. I have a master’s degree in my field, with a deep knowledge of the issues surrounding it in my own country. (I’m sorry, I can’t identify the field now.) My boss, the program director, is not a specialist in this field. Actually, he is from an unrelated background; and yes, now he’s managing a multi-million dollar program in East Africa. Just where am I in what M– refers to as the ‘big boys club’ that is discussing how to run programs for my country, using all the knowledge that they pick from my brain?

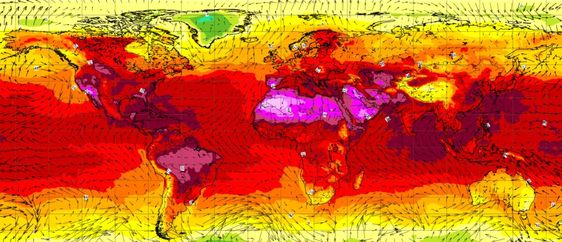

The picture above is reminiscent of what happens in the world of development. Outsiders, and quite frankly, some wet behind the ears, are the ones trying to tackle complex problems of the South, without the real participation of its professionals. Do they know enough?

“Sometimes I feel like a signboard that points in the right direction but never gets to the destination.”

The professionals in the South often play the role of guide, educator, and source of information. You see, when many development workers, also known as the ‘expatriates,’ come from the North to the South, especially for the first time, they hardly know the local situation. They depend on the local professional for guidance. Sometimes I feel like a signboard that points in the right direction but never gets to the destination. Armed with this information, the expat can develop project proposals, win big grants, and move to the South to solve my problems. They make me do the work (I am not lazy by the way) then report to donors and international forums essentially becoming the go-to expert on matters in the Southern hemisphere.

There is also another peculiar thing that bothers me too. There just seems to be this glass ceiling for the Southern professional, who is not able to rise beyond a certain level. There are occasional exceptions, but this is the general rule. This often is driven by the origin of both the funding and nationality. (I am being polite here; one day I will tell it as it is.) Look at the organizational structure of any INGO and tell me where the Southern professional is.

The local professional is at the frontline implementing program activities, creating awareness and buy-in from local communities, governments, and stakeholders. Sometimes the local professional may not even believe in what he or she is promoting; the strategies have been developed elsewhere, with pictures painted to endear donors and not grounded in the local situation. Government is often all too happy to have people bring in resources to help with solving problems (save for civil problems), which it does not have resources to solve, no matter how relevant, irrelevant, duplicating, excluding, or whatever. After all, the NGO Sector in Kenya is estimated to bring in Ksh130b ($130m) annually which is bigger than our coffee subsector and about the size of the tea subsector. We all need money!

“…the NGOs will convince the government to allow the expat to work the country to pass on skills to the locals. In most cases, this is often forgotten once the authorization to work is provided.”

Sometimes the local professional provides justification for the expat to be around. In Kenya for example, the NGOs will convince the government to allow the expat to work in the country to pass on skills to the locals. In most cases, this is often forgotten once the authorization to work is provided. The end justifies the means, I step on your shoulders to get to where I want to go. I am reminded about Joash, who works in the community health awareness unit, was nominated as an understudy for one of the expats in the organization. I asked him about whether he was ever trained or mentored in any way. He placed his finger on the skin under one of his eyes and pulled open (this is African for “Never, no, I only saw it on the paper it was written on, never happened”). Often once the expat leaves, they are replaced by another and the whole story starts all over again.

On the flip side, the local professional does have a job, otherwise, they would be unemployed. My earnings place me right in the middle class — or it is a middle-class wannabe? I can afford a car, take my children to a private school, and afford the occasional holiday among other luxuries. Should I be talking?

Since I cannot stop wondering, I wonder about the person at the bottom of the pyramid in whose name the donor funds are raised? How do they benefit? All too often, the money benefits the few at top of the pyramid and benefits diminish as the pyramids widen. It is all upside down.

The author: This was submitted to us by someone working at an NGO in Kenya who has asked to remain anonymous. It was written a few years ago, when the author worked at a different NGO, about his/her experiences there. While we would prefer that the author be identified, the author’s reasons for preferring anonymity are explain in the story. We invite others, who work for NGOs in the South, to comment below about whether their own experiences are similar. The author is on Twitter at @NGOSceptic.

Comments from Twitter

We announced this story on Twitter, where readers made these comments:

Bally, @Erastus___: The stereotype and racism in those guys is deep, most of them feel we Africans cannot do it as they can. I mean it’s our natural habitat, we know the problem more than they do. I hate it. Those NGOs really need to be honest with their intentions.

Stephen Cutler, @cutleri4c: USAID has been doing projects in the Philippines for 50+ years. Still US companies as contractors abs usually a US chief, with almost all local staff. Apparently not much real development in 50 years.

C.E.O., @MrsCemmo: While on that. One day I’ll bring this up in ‘DETAIL’. How come compensation differs for people of different Nationalities, yet… the western governments selling point is ‘EQUALITY’!!???

Blen, @hamezene: I can tell you, people who can do the job better than the foreign stuff get paid 1/4 of the salary, the foreign stuff gets housing and a car with a driver, which drives rent and house prices high and make life miserable for the locals

Lindiwe Ngwenya, @lin_ngwenya: It’s not the non-commitment to mentoring that bothers me. It’s how those with unrelated qualifications and work experience are leading those with in-depth country or regional experience accompanied by the relevant qualification. Yet the latter group has no career progression.

Osman, @inboorling_: Check out how ngo expats live in those third world countries, I think that says more than enough…

First of my kind.., @Jojoleedynasty: White people coming to work in Africa are called expatriates while black people working in the white man’s land are called immigrants.

1 Comment

Pingback: best therapist website design