Most Ultra-Processed Food, it’s not food. It’s an industrially produced edible substance. – Fernanda Rauber

What makes ultra-processed food so irresistible? Chris van Tulleken reveals the secrets of the food industry.

from NRK texted in Norwegian

First Published on Bergensia January 16, 2025 – Updated July 27, 2025 with statistics on Norway from Fedon Lindberg: Kampen mot kreft

Why Do We All Eat Stuff That Isn’t Food… and Why Can’t We Stop?

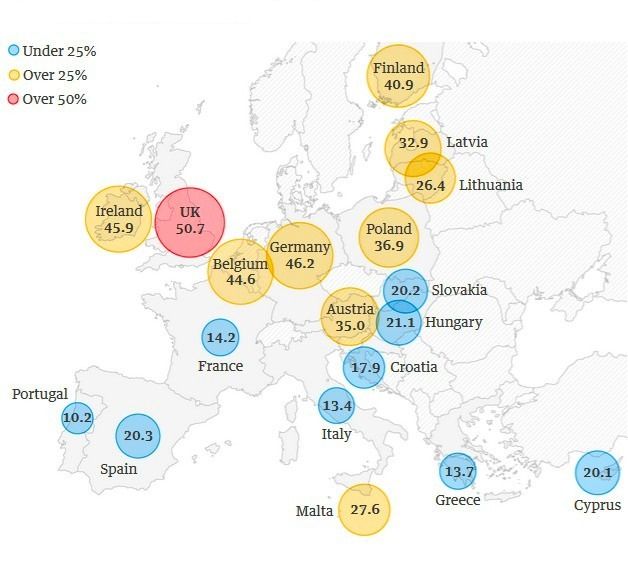

Ultra-Processed Food as a Share of Household Purchases by Country

In Norway, as early as 2013, ultra-processed foods accounted for 59% of the grocery products sold and represented nearly half of the grocery expenses.

[USA and UK is over 60% – teens often over 80%, 2020, Canada and Australia following close]

If the food is covered in plastic and there’s a label with an artificial sweetener, the word ‘flavoring,’ some health benefit, or an ingredient you don’t recognize or couldn’t find in your kitchen, it’s probably Ultra-Processed Food. When in doubt about if it’s Ultra-Processed Food, it’s undoubtedly not homemade food!

If you only read one diet or nutrition book in your life, make it this one.

– Bee Wilson

A devastating, witty and scholarly destruction of the shit food we eat and why.

– Adam Rutherford

Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: In a rigorously controlled clinical trial conducted by the National Institutes of Health in the United States, researchers compared what happened when a group of subjects followed a diet consisting of ultra-processed foods for two weeks and then a diet made from scratch. Both diets contained equal amounts of fat, sugar, sodium (salt), and fiber, and all subjects were allowed to eat until they were full. To the researchers’ surprise, people ate significantly more calories when given ultra-processed foods. On average, they consumed approximately 500 more calories per day. Over a year, that would amount to 182,500 extra calories and approximately 25 kg of extra body weight.

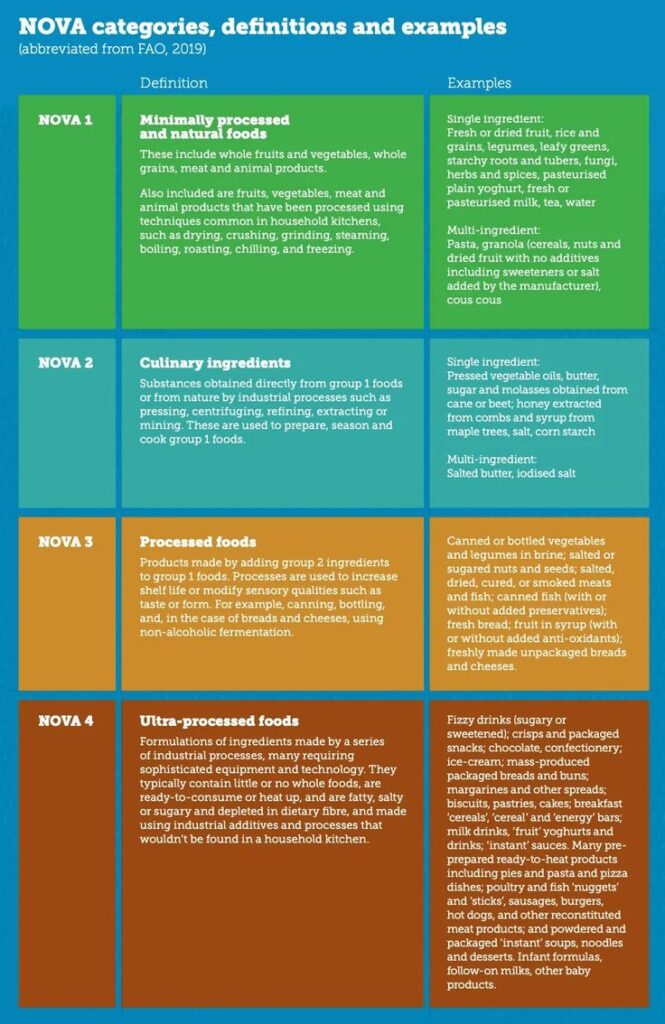

The term “ultra-processed food” was first coined and notably mentioned in the scientific literature in 2009 by Carlos Monteiro in the context of the NOVA food classification system. This system categorizes food based on the extent and purpose of industrial processing, with ultra-processed foods in category 4.

We have entered a new ‘age of eating’ in which most of our calories come from a novel set of substances called Ultra-Processed Food. These products are industrially processed, designed, and marketed to be addictive. But do we understand what they’re doing to our bodies?

Join Chris in this ground-breaking book as he lives on a diet of almost nothing but UPF while traveling through the worlds of food science, history, and economics. What’s happening in our bodies and brains when we eat UPF? What makes it the number one cause of diet-related diseases, including obesity and early death? How does it contribute to environmental destruction, and why is it nearly universal in our diets? You’ll learn what we can do about UPF and the companies that make it.

Ultra-Processed People exposes why we’ve lost an understanding of how weight gain works, why UPF should be looked at as an addictive substance, and why none of it is your fault. We have the right to know what we’re eating and the right to good, affordable food. So eat along with Chris as you read; as he did, you may find that the foods you’ve previously felt addicted to become less and less appealing.

The New Yorker by Dhruv Khullar January 6, 2025

Why Is the American Diet So Deadly?

A scientist tried to discredit the theory that ultra-processed foods are killing us. Instead, he overturned his own understanding of obesity.

In recent years, dozens of studies have linked ultra-processed fare to health problems such as high blood pressure and heart attacks, and also to some problems that one might not expect: cancer, anxiety, dementia, and early death.

“Even today, when people talk about what we need to eat more of, they talk about food,” she said, her voice rising. “But when they talk about what we need to eat less of, they switch to nutrients!”

Food scientists are investigating a possible cause of the obesity epidemic, which wasn’t named until the twenty-first century: ultra-processed foods.

Illustration by Allan Sanders

The harsh reality of ultra-processed food – with Chris Van Tulleken

Buy Chris’s book here: https://geni.us/YqqoR

00:00 Why we need to talk about our diets

03:40 We’re part of an experiment we didn’t sign up for

10:05 What is ultra processed food?

12:50 What Donald Trump got right about UPF

14:20 What Diet Coke does to your health

17:53 How ultra processed food is made

23:55 Why does ultra processed food cause obesity?

29:05 Doesn’t exercise burn calories?

35:37 What about willpower and diet?

38:18 What role do stress and genes play?

39:45 How does ultra processed food harm us?

47:33 How UPF affects the planet

50:41 Ultra processed food is addictive

52:25 The food system is financialised

54:28 What are the solutions?

This lecture was filmed at the Ri on 19 September 2023 through the generous support of Digital Science.

The industrialization and commercialization of food have transformed our diets, whereby most of our calories come from an entirely novel set of substances. Ultra Processed Food (UPF) now makes up 60% of the average diet in the UK and USA. It is highly processed, highly addictive, and largely unhealthy.

Join award-winning broadcaster, practicing NHS doctor, and leading academic Chris van Tulleken as he explores the invention of UPF and its impact on our health and weight – from altering metabolism and appetite to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and tooth decay. Chris uncovers the limitations of relying solely on exercise and willpower to combat the health risks of high UPF diets. Drawing on his own experiment of eating an 80% UPF diet for one month, he provides solutions for both individuals and policymakers to challenge this unregulated industry.

Chris van Tulleken is an infectious diseases doctor at UCLH and one of the UK’s leading science broadcasters. He has won two BAFTAs for his long-running CBBC series Operation Ouch, co-presented with his twin brother Xand, and hosted numerous programs across the BBC. Following his BBC One documentary ‘What Are We Feeding Our Kids?’ and the chart-topping podcast ‘A Thorough Examination – Addicted to Food,’ Chris has become the UK’s go-to expert on ultra-processed food. Chris trained at Oxford and has a PhD in molecular virology from University College London, where he is now an Associate Professor. His research focuses on how corporations affect human health, especially in the context of nutrition.

Where ‘you’ end and not ‘you’ begin is far from clear. You’re covered in microbes that keep you alive — they’re part of you as much as your liver is — but those same microbes can kill you if they get into the wrong area of your body. Our bodies are much more like societies than like mechanical entities, compromising billions of bacteria, viruses, and other microbial life forms, but just one primate. – Chris van Tulleken

Life has only two projects: reproduction and extracting energy to fuel that reproduction. Over billions of years, our bodies have superbly adapted to using a wide range of food.

But over the past 150 years, food has become … not food.

We’ve started eating substances constructed from novel molecules and using processes never previously encountered in our evolutionary history, substances that can’t even be called ‘food.’

Our calories increasingly come from modified starches, from invert sugars, hydrolyzed protein isolates, and seed oils that have been refined, bleached, deodorized, hydrogenated – and interesterified. And these calories have been assembled into concoctions using other molecules that our senses have never been exposed to either: synthetic emulsifiers, low-calorie sweeteners, stabilizing gums, humectants, flavor compounds, dyes, color stabilizers, carbonating agents and bulking – and anti-bulking – agents.

These substances entered the diet gradually at first, beginning in the last part of the nineteenth century. They gained pace from the 1950s onwards to the point that they now constitute the majority of what people eat in the UK and the USA and form a significant part of the diet of nearly every society on earth.

At the same time as we’ve entered this unfamiliar food environment, we’ve also moved into a new parallel ecosystem, one with its own arms races that are powered not by the flow of energy but by the flow of money. This is the new system of industrial food production. In this system, we are the prey, the source of money that powers the system. The competition for that money, which drives increasing complexity and innovation, occurs between an entire ecosystem of constantly evolving corporations, from giant transnational groups to thousands of smaller national companies. And their bait for extracting the money is called ultra-processed food, or UPF. These foods have been put through an evolutionary selection process over many decades, whereby the products that are purchased and eaten in the greatest quantities are the ones that survive best in the market. To achieve this, they have evolved to subvert the systems in the body that regulate weight and many other functions.

Utra-Processed Food now comprises as much as 60 percent of the average diet in the UK and the USA. Many children get most of their calories from these substances. UPF is our food culture, the stuff from which we construct our bodies. If you read this in Australia, Canada, the UK, or the USA, this is your national diet.

Ultra-Processed Food has a long, formal scientific definition, but it can be boiled down to this: if it’s wrapped in plastic and has at least one ingredient you wouldn’t usually find in a standard home kitchen, it’s UPF. Much of it will be familiar to you as ‘junk food’, but there’s plenty of organic, free-range, ‘ethical’ UPF too, which might be sold as healthy, nutritious, environmentally friendly, or useful for weight loss (it’s another rule of thumb that almost every food that comes with a health claim on the packet is a UPF).

The formal UPF definition was first drawn by a Brazilian team headed by epidemiologist Carlos Augusto Monteiro in 2010 when they introduced the NOVA classification. Biscuit consumption in Brazil grew by 400 percent between 1974 and 2003, and soft drink consumption also grew by 400 percent. The link between the popular products causing the problem was clear: they were all made from deconstructed, modified ingredients mixed with additives and frequently aggressively marketed.

Since then, a vast body of data has emerged in support of the hypothesis that UPF damages the human body and increases rates of cancer, metabolic disease, and mental illness, that it damages human societies by displacing food cultures and driving inequality, poverty, and early death, and that it damages the planet.

The Ultra-Processed food system is the leading cause of declining biodiversity and the second largest contributor to global emissions. UPF is thus causing a synergistic pandemic of climate change, malnutrition, and obesity. This last effect is the most studied, but UPF doesn’t cause heart disease, strokes, and early death simply because it causes obesity. The risks increase with the quantity of UPF consumed, irrespective of weight gain. Additionally, people who eat UPF and don’t gain weight have increased risks of dementia and inflammatory bowel disease.

US National Health surveys show that — in white, Black, and Hispanic men and women of all ages — there was a dramatic increase in obesity beginning in the 1970s. The idea that there has been a simultaneous collapse in personal responsibility in both men and women across age and ethnic groups is not plausible.

For the past thirty years, under the scrutiny of policymakers, scientists, doctors, and parents, obesity has grown at a staggering rate. Fourteen government strategies containing 689 wide-ranging policies have been published in England during this period. Still, among children leaving primary school, rates of obesity have increased by more than 700 percent and rates of severe obesity by 1600 percent.

Children in the UK and the USA, countries with the highest rates of UPF consumption, aren’t just heavier than their peers in nearly all other high-income Western countries; they’re shorter, too. This stunting goes hand in hand with obesity around the world, suggesting that this is a form of malnutrition rather than a disorder of excess.

Five-year-old children in the UK don’t just have some of the highest rates of obesity in Europe, they are also among the shortest by a very significant amount – more than five centimeters shorter than Danish and Dutch children of the same age, who by the way, also have some of the lowest rates of obesity.

In the UK, overweight now affects more than a quarter of children and half the adult population. Policies in the UK and almost every other country have failed to solve obesity because they don’t frame it as

a commerciogenic disease— that is, a disease caused by the marketing and consumption of addictive substances [like drugs and cigarettes].

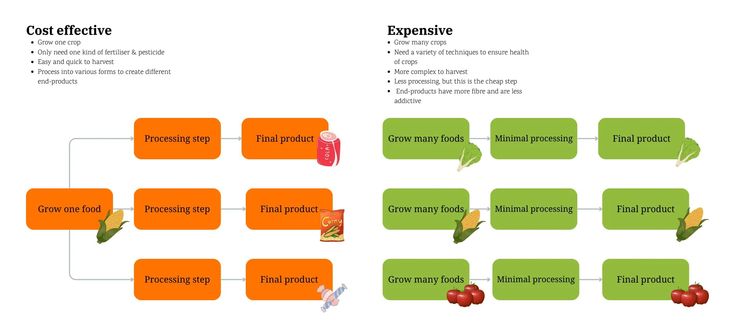

Ultra-Processed Food saves money

Even before the current cost-of-living crisis, British consumers spent only 8 percent of their household budget on food, lower than anywhere else except the USA, where people spend 6 percent. Germany, Norway, France, and Italy all spend 11 – 14 percent of their budget on food, and households in low-income countries spend 60 percent or more.

In the UK (and many other countries), housing, fuel, and transportation are fantastically expensive, squeezing that food budget. For rich people, this isn’t a problem. However, an analysis by the Food Foundation shows that the poorest 50 percent of households would have to spend almost 30 percent of their disposable income on food if they wanted to eat a diet that adheres to our national healthy eating guidelines. The poorest 10 percent of households by income would need to spend almost 75 percent.

For poor people, UPF provides a kinder egg solution: cheaper, quicker, and supposedly just as nutritious—if not more so—than foods and meals that need home preparation.

During Napoleon’s era, in 1869, his nephew organized a competition where a French chemist and pharmacist, Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès, came up with the first ultra-processed butter substitute from solid cow fat named Oleomargarine. By 1930, producing a solid margarine from liquid whale oil was possible. The spread melted at 30’ Celsius and would, therefore, melt in the mouth. By 1960, whale oil comprised 17 percent of the total fats used in margarine production. By 1907, the early Procter & Gamble Company (who would go on to make Pringles) had worked out how to turn cottonseed oil into solid edible fat.

In a chemical process known as RBD, oils are refined, bleached, and deodorized. This process is used to make soybean oil, palm oil, canola (rapeseed) oil, sunflower oil – four oils comprising 90 percent of the global market — and other non ‘virgin’ or ‘cold pressed’ oils.

Having solved the problems of cottonseed oil, P&G began a large campaign marketing the de-toxified oil as Crisco, an acronym for crystallized cottonseed oil. By 1920, the use of the product was widespread. Crisco shortening, essentially a fake lard, was possibly the first mass-produced UPF!

They can simply use whichever happens to have the cheapest market price. To avoid the cost of re-writing the packaging, they can stick to these Uncle Tom Cobley labels’ with all the different fats listed.’

The war in Ukraine caused sunflower oil prices to spike!

If you see any of these fats on a label that you wouldn’t use at home (like any modified palm fat, for example), then the product is UPF. In the race toward the bottom, chicken fat could end up in your ice cream burp!!

Nazi Germany invented the first synthetic food – ‘Speisefett’; it was white, tasteless, and waxy and still felt a long way from butter. But that was a trivial problem for a chemist like Arthur Imhausen. Buttery taste comes from a chemical called diacetyl, which is still used to flavor microwave popcorn. (Workers in the factories that manufacture popcorn get a disease that destroys their lungs, which is officially called bronchiolitis obliterans but also known as ‘popcorn workers’ lung.’ Diacetyl has also been detected at very low levels in some vape liquids.) Mixing the fat with diacetyl, water, salt, and a bit of beta-carotene for color allowed Imhausen to complete the transformation of German coal into ‘coal butter.’

Wilhelm Keppler, a politician and a key figure in linking German companies up with the Nazi regime and making Germany self-sufficient, was delighted and wanted to turn the achievement into confidence-bolstering propaganda. But there were two problems. First, Imhausen’s mother was Jewish. Back in 1937, when the Deutsche Fettsäure Werke was being put into operation, Keppler had written to leading Nazi Hermann Göring to ask whether he was sure he wanted to take part in the inauguration considering the fact that Imhausen was of ‘non-Aryan descent.’ Göring asked Hitler about it, who allegedly replied, ‘If the man really made the stuff, then we’ll make him an Aryan!’

And so it was that Göring wrote the following to Imhausen: ‘In view of the great merits you have rendered in the development of synthetic soap and synthetic cooking fat from coal, the Führer, at my suggestion, approved your recognition as a full Aryan.

So that was the first problem taken care of. The second problem was the coal butter’s safety: if it was going to be food for troops, it couldn’t impair their performance. In 1943, Imhausen authored an article in Colloid and Polymer Science with the title: ‘Fatty acid synthesis and its importance for securing the German fat supply.’ The article described in great detail the process for the manufacture of synthetic fat and made an oblique reference to the safety testing: ‘Thousands of tests, led by Director Prof Fr Flössner, confirmed the high value of synthetic cooking fat and made it the first synthetic food in the world to be approved for human consumption.

Otto Fl¨ssner was the chief of the Physiological Department of the Reich Working Group for Public Nutrition. And though it’s true that he did extensive testing on the synthetic fat, what is less well referenced is the context of the experiments, which were conducted on more than 6.000 prisoners in concentration camps.

There is an inexorable logic in all industrial food: to reduce the time workers require for a meal

While most studies focus on obesity, there is also evidence that increased Ultra-Processed Food intake is strongly associated with an increased risk of:

- death – so-called all-cause mortality

- reduced fertility (and, according to some experts, penile shrinkage) by plastics from the UPF packaging, especially when heated

- cardiovascular disease (strokes and heart attacks)

- cancers (all cancers overall, as well as breast cancer specifically)

- type 2 diabetes

- high blood pressure

- fatty liver disease

- inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohns disease)

- depression

- worse blood fat profile

- frailty (as measured by grip strength)

- irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia (indigestion)

- dental caries in school-aged children in industrialized countries

- dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

The last one may be most alarming for those with a family history of dementia. In 2022, a study published in the journal Neurology looked at data from 72.0000 people. Increasing intake of UPF by 10 percent was associated with a 25 percent increase in the risk of dementia and a 14 percent increase in the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

It is not about sugar or exercise

Amy Luke and Kara Ebersole of Loyola University showed no difference in total energy expenditure between a cohort of women in rural Nigeria and another in suburban Chicago [we burn about 2500 calories]. This pattern holds for all human populations ever studied. The same thing has been reported in non-human primates like monkeys and apes: captive populations burn the same number of calories as their counterparts in the wild.

In 2015, Coca-Cola published a ‘transparency’ list of experts and projects it funded but proved less than transparent. For every author Coke disclosed, there were another four whom they didn’t. Respectable health journals shouldn’t publish research funded by Coca-Cola any more than they should publish health research funded by the tobacco industry.

Food deserts and food swamps

These are places where shops don’t sell fresh food and healthy groceries, and only UPF is available. According to the US Department of Agriculture, there are over 6,500 food deserts in the USA. They’re found in areas with higher levels of poverty and higher percentages of ethnic minority populations. In the UK, over 3 million people do not have a shop selling raw ingredients by public transport within 15 minutes of their homes. This means it is challenging to source real food – let alone cook it.

Food swamps are similar to food desserts. Fresh food may be available, but it is submerged in a swamp of fast-food outlets selling UPF. Think of the British city Leichester.

Frozen meals and later TV dinners were, of course, invented in the USA. But now the UK population eats more of these ready meals than any other country, as almost 90 percent eat ready meals regularly. It’s rare to leave anything behind in UPF packaging.

Ultra-Processed Food is proprietary and thus made for growth and advertising

Turkey Twizzlers is a notorious product banned from school meals in the UK more than a decade ago because it seemed so unhealthy to food activists. The original version had up to forty ingredients — only a third of a Twizzler was actual turkey meat. The new version is still less than two-thirds turkey, and the manufacturers have managed to get it down to a mere thirty-seven ingredients.

Meals took on a uniformity: everything seemed similar, regardless of wether it was sweet or savory. I was never hungry, but I was also never satisfied. The food developed an uncanny aspect, like a doll that looks just the wrong degree of realistic and ends up seeming corpselike. – Chris van Tulleken, on a Ultra-Processed Food diet experiment

Ultra-Processed Food hacks our brains

Ultra-Processed Food seems more addictive for more people than many addictive drugs. Of course, many people are able to consume UPF in moderation, but that’s also true for cocaine, alcohol, and cigarettes. Compare the numbers. The transition from trying UPF to being unable to stop using it is extremely high: 40 percent of the US population lives with obesity, and we know that the majority of them will try to lose weight in a given year. Cessation rates are so low as to be non-existent. There is no other drug that, haven tried it, 40 percent of people will continue to use it regularly despite negative health consequences (a definition of addiction). For example, over 90 percent of people in the USA consume alcohol, but only 14 percent develop an alcohol-use disorder. Even with illicit drugs like cocaine, only 20 percent of users go on to become addicted.

Drugs of abuse and UPF share certain biological properties. Both are modified from natural states so that there is rapid delivery of the rewarding substance. The speed of delivery is strongly linked to addictive potential – cigarettes, snorted cocaine, and shots of alcohol. Drug addiction and food addiction share risk factors like a family history of addiction, trauma, and depression, indicating that UPF may be performing the same function as the drugs in those people.

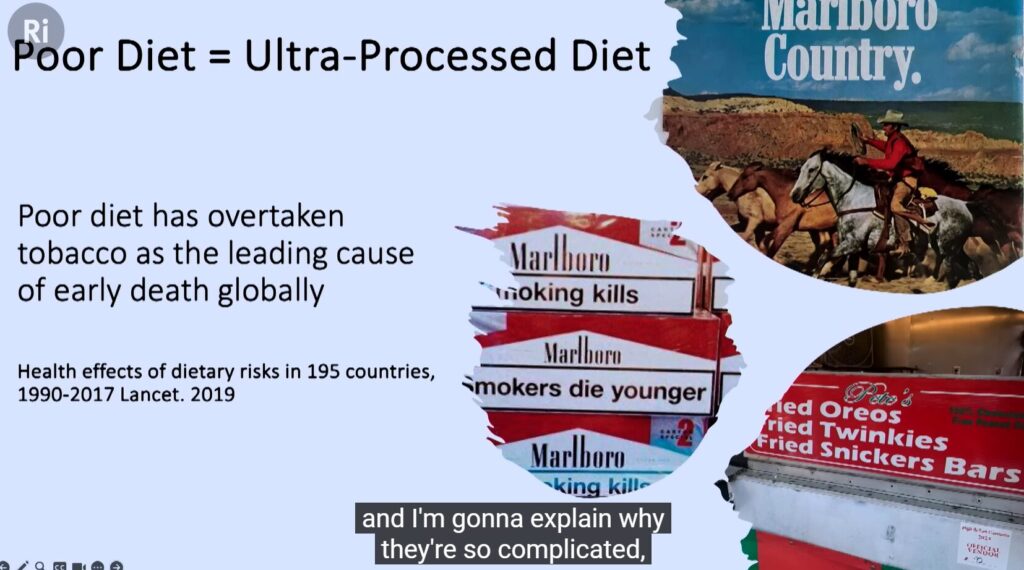

People report similar addiction symptoms with UPF and other addictive substances, including craving, repeated unsuccessful attempts to cut down, and continued use despite negative consequences. And those negative consequences are severe: a poor diet may have worse effects for many people than even very heavy smoking.

Neuroimaging has shown similar patterns of dysfunction in reward pathways for both food addiction and substance misuse. These foods also appear to engage brain regions related to reward and motivation, similar to addictive drugs.

Once you pop you can’t stop. Pringles slogan

You may find it hard to consider UPF as equivalent to cigarettes, but poor diet – a high UPF diet is linked to more deaths globally than tobacco, high blood pressure or any other health risk – 22 percent of all deaths. Since the risks are so high, there may be advantages to considering UPF as an addictive substance. It may help to reduce some of the stigma, guilt, and blame around obesity and excess consumption, just as campaigners achieved with smoking decades ago.

Will Ultra-Processed Food affect children’s IQ and their social performance? We don’t know what’s happening to children’s brains.

People living with overweight quitting Ultra-Processed Food think they are going to lose fat, but it may actually modify the brain in a very positive way that affects other areas of life. I suspect that we might see people’s concentration and memory improve, though we need to prove that.

– Professor Claudia Gandini Wheeler-Kingshott, UCL Institute of Neurology

UPF is pre-chewed

If you eat a whole apple, your stomach fills more and differently than from an apple smoothie or apple juice, even though the smoothie consists of the exact same ingredients: apple fiber 2,5% and apple juice 97,5%. Softness is one of the characteristics Kevin Hall identified as a near-universal quality of Ultra-Processed Food. The softness problem is backed up by evidence suggesting that Ultra-Processed Food is eaten far more quickly than whole or minimally processed food, meaning more calories can be consumed per minute.

In many places, honest craft bread that is not Ultra-Processed is hard to find as it only makes up 5% of the market, and if you can find it, it will be pretty expensive. The “healthy” branded ready-made baguette or sandwich you buy quickly on your way to or from work is probably Ultra-Processed to maintain an economical shelf life for more than a day.

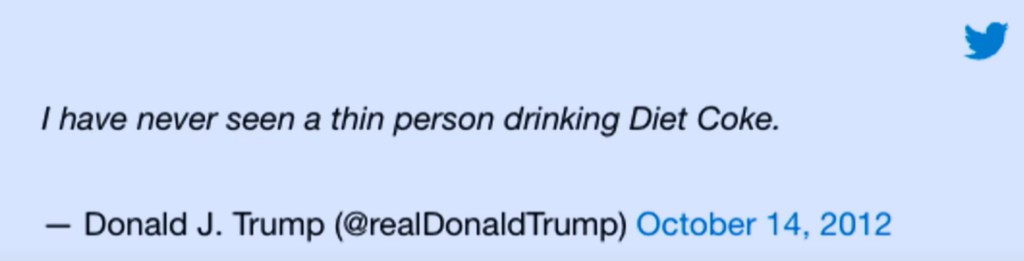

Even Trump knows a thing or two about Ultra-Processed Food

It is widely reported that Diet Coke gives higher cravings than real Coke.

It might seem obvious that as artificial sweeteners don’t contain calories, they can’t cause obesity.

But if you can understand why a zero-calorie drink could lead to weight gain and metabolic disease, then you will have understood one of the most fundamental ways that UPF seems to cause health problems. If food contains an artificial sweetener, it is, by definition, UPF. The most commonly consumed are cyclamate and saccharin – the cheapest and oldest – and the global market is worth around $2.2 billion a year. These artificially sweetened beverages are even more strongly linked to obesity and type 2 diabetes than their original sugar drinks. An alarming study indicates more severe effects when mixing sugar and artificial sweeteners.

Dysregulatory bodies – in the US the food industry is regulates itselves

Big Food like Nestlé replaces traditional diets with KitKats

Ultra-Processed Food Kills Biodiversity

The important question is not ‘What is the carbon footprint of a particular product?’ but ‘Which foods would we find in a food system that helped to resolve the climate and nature crisis?’

Of the thousands of different strains of plants and breeds of animals that have been cultivated since the birth of agriculture, just twelve plants and five animals now make up 75 percent of all the food eaten and thrown away.

Palm is the oil we now eat most, and increasingly well known for its environmental impact. The fires from clearing of forest to grow palm in Indonesia on several single days in 2015 emitted more carbon dioxide than the entire United States economy. Around three-quarters of the palm oil produced is used in Ultra-Processed Food. This shows how corrupted our food system has become, because these highly processed oils [RBD: refined, bleached and deodorised] still counts as simple kitchen ingredients or NOVA group 2. There is a separate discussion about their effect on human health that I won’t go into here.

The Nestlé Brand survived it’s Baby Formula Scandal and fully recovered facing George Clooney

[made with Grok 2] The Nestle Baby Formula scandal primarily unfolded in the 1970s, focusing on the company’s marketing practices for infant formula, particularly in developing countries. Here’s an overview:

- Marketing Tactics: Nestle was accused of aggressively marketing its baby formula by distributing free samples in maternity wards and using sales representatives dressed as nurses to convince new mothers that formula was superior to breastfeeding. This practice led to a significant drop in breastfeeding rates as mothers’ milk production diminished due to lack of demand, making formula a necessity even when it was not the best option.

- Health Implications: The scandal highlighted severe health risks associated with formula use in areas where clean water was scarce. Mixing formula with contaminated water led to malnutrition, diarrhoea, and deaths among infants. Additionally, many families could not afford continuous purchases of formula, leading to dilution of the product, which further exacerbated health problems.

- Public Outcry and Boycott: In 1977, a global boycott against Nestle was launched due to these unethical practices. This boycott was supported by various organizations like the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN) and Save the Children. It spread from the United States to Europe, severely impacting Nestle’s reputation.

- Legal and Ethical Responses: Nestle faced legal challenges, notably when it won a libel suit in Switzerland against claims that it was responsible for infant deaths, although the judge criticized their marketing methods. The controversy led to the adoption of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1981, aiming to regulate how infant formula is marketed to prevent similar issues.

- Long-term Impact: Even after the boycott ended in 1984 with Nestle agreeing to comply with the WHO code, criticisms of Nestle’s marketing practices continued, with reports into the 2000s and beyond showing that the company still engaged in practices that undermined breastfeeding in developing countries.

- Recent Developments: More recent investigations have revealed that Nestle continues to add sugar to baby products in some developing countries, contrasting with practices in Europe, where no sugar is added, highlighting ongoing ethical concerns about double standards in marketing and product formulation.

The Nestle Baby Formula scandal is a pivotal case in discussions about corporate ethics, marketing, public health, and the responsibilities of multinational corporations in global markets.

1 Comment

Pingback: Cancer: A Food-Borne Illness, a documentary by Grace Price - Bergensia