Alfons Weersink, University of Guelph and Michael von Massow, University of Guelph

Even before the Russian army crossed into Ukraine, food prices had been on the rise for the past year. But the world has seen large jumps in the cost of food over the the last two months.

Globally, food is 20 percent more expensive now than it was a year ago, with prices rising four percent since January this year. In Canada, the annual food inflation rate hit 6.5 percent in January, the highest in more than a decade.

A variety of factors have caused these price increases, including rising transportation costs, supply chain disruptions and rising commodity prices, such as corn and wheat.

The war in Ukraine will continue to push up food prices as the supply from the “Breadbasket of Europe” is cut in the short term and, possibly, the long term depending on how the conflict plays out.

War and wheat prices

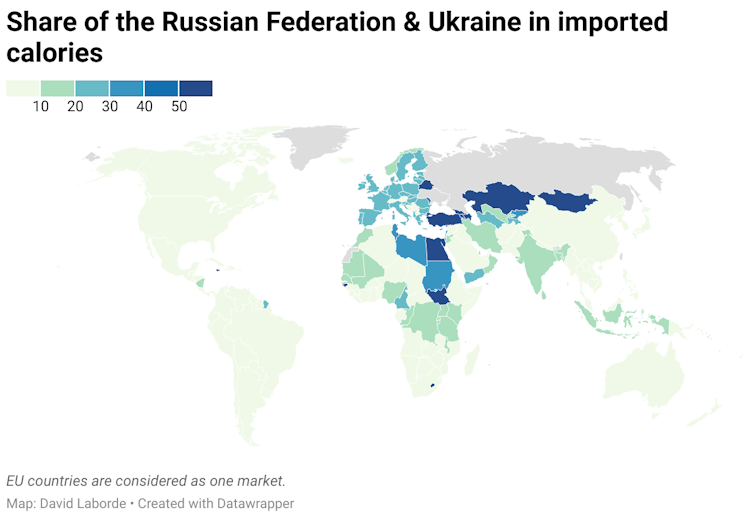

Ukraine and Russia represent around 10 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively, of global wheat production, and nearly 30 per cent of all wheat exports come from these two countries. Most of this wheat is imported by countries in the Middle East and North Africa.

For example, Lebanon and Tunisia, two countries with vulnerable economies, import more than half of their wheat from Ukraine. Consequently, production from Ukraine, or lack thereof, influences global food security. While Ukraine has been a consistent supplier in the past, we’ve seen global shortages impact food security before.

The wheat export supply chains from Ukraine have been disrupted by the conflict. Port facilities in Ukraine have suspended commercial operations, preventing the outflow of the wheat crop harvested in 2021.

While the 2022 wheat crop was planted last fall, other crops need to be planted soon. Final production for all crops in Ukraine depends on farmers being in their fields, not fighting a war, to fertilize, harvest and move the crop, if the supply chain is sturdy enough.

Since Russia invaded the Ukraine, concerns about supply disruptions have pushed up wheat prices on the Chicago Board of Trade by over 50 per cent to nearly US$13 per bushel. Prices rose by the maximum possible allowed by the board for the first five trading days of March — an unprecedented increase.

Domestic and international impacts

Higher wheat prices will translate into higher food prices for all. But the impact will depend on the farmer share of their food dollar, and the percentage of an individual’s income spent on food.

A significant increase in the price of wheat won’t mean an equally large increase in the price of bread in Canada and the United States. This is because the average farmer’s share for every dollar spent on a loaf of bread is four cents (four per cent). For flour, which is less processed than bread, the farmer’s share is 19 cents (19 per cent).

Overall, the farmer share of the food dollar in the U.S. is approximately 15 per cent, and it’s slightly higher in Canada. The greater degree of value added to the product beyond the farm gate, the lower the farm share.

In contrast, there is a strong correlation between wheat price and bread price in developing countries, where the farmer share of the food dollar can be close to 50 per cent. Wheat price increases will have a significant impact on the price paid for wheat-based products.

Income matters too

The relative effect of any food price increase will also depend on the share of income spent on food. This share declines with the wealth of the nation or consumer, as summarized by Engel’s Law.

The average Canadian household spends less that 10 percent of its income on food. An increase in the cost of food can be absorbed, although it will lower the amount of disposable income for other goods and services. Food price increases take away income for things like leisure activities.

In less-developed countries — and for poorer households domestically — the share of income spent on food can be above 40 percent. For example, Lebanon and Yemen will need to import wheat at a higher cost than what they were paying for wheat from Ukraine, in a tight market. The large price increase will force a corresponding large increase in the price of bread, given the higher farmer share of the food dollar.

Egyptian traditional ‘baladi’ flatbread, at a bakery, in el-Sharabia, Shubra district, Cairo. The war in Ukraine has stopped shipments of wheat and other staples to North Africa and elsewhere. (AP Photo/Nariman El-Mofty)

The financial consequences for those consumers will be large given the relatively high percentage of income spent on food, and bread in particular. With less room to divert income from other expenditures, food security may be compromised. Low-income Canadians who are also facing rent increases will be similarly squeezed.

Another factor influencing the distributional impact of an increase in wheat price is whether the household or region is a wheat producer or consumer. Developing countries with a large share of poor households in urban areas are especially vulnerable to the financial hit of an increase in wheat price.

A decade ago, when crop prices last rose significantly, food riots broke out in countries with a high concentration of poor consumers in urban areas, including Egypt, Mexico and Pakistan. In contrast, other developing countries with a high proportion of small farms can sell some of their crop into the market. These farmers benefit from a commodity price increase and the benefits also accrue to the broader economy as these small farmers have a bit more money to spend.

The compounding factor of energy prices

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has also shocked energy markets. Russia produces 23 percent of the world’s natural gas, and about 40 percent of the European Union’s natural gas comes from Russia. Russia is also a major exporter of oil.

Sanctions have helped pushed up Brent crude oil prices by more than 60 percent since the beginning of the year, although they are not the only reason the price of oil is high.

In developed countries, including Canada, the increase in energy prices is the major driver of food inflation. The food supply chain from the production at the farm level to the transportation, processing, storing and eventually selling at retail, relies heavily on energy. In developing countries, the increase in energy prices does not have the same relative impact but it will further exacerbate the increase in food prices.

The impacts felt most by the most vulnerable

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has set off a series of direct and indirect supply shocks to commodity markets. The impacts of these shocks will vary with the degree of reliance on wheat and energy from these countries.

The most vulnerable are net importing food countries that are dependent on Ukraine. The risk to global food security in these regions can be mitigated to a degree by allowing food trade to continue. One means is to avoid sanctioning Russian food exports, and the other as advocated by G7 agricultural ministers, is for other countries to not use export bans that would restrict movement of food out of their country.

However, the only way to ultimately reduce the impact is stop the conflict in Ukraine and get wheat flowing again.![]()

Alfons Weersink, Professor, Dept of Food, Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Guelph and Michael von Massow, Associate Professor, Food Economics, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

13 Comments

Pingback: Russian losses in Ukraina "special military operation" - Bergensia

Pingback: bossa nova music

Pingback: lotto77

Pingback: หวยหุ้น อินเดีย คืออะไร

Pingback: นำเข้าสินค้าจากจีน

Pingback: เว็บปั้มวิว

Pingback: แทงบอลสเต็ป 2 คู่ ไปกับ เว็บตรง LSM99

Pingback: fk brno 7.5

Pingback: best disposable vape

Pingback: Israeli Genocide in Gaza resumes, water and food are weaponized - Bergensia

Pingback: Happyluke ใช้งานง่าย

Pingback: ดูบอลสด66

Pingback: massage Bangkok