Israel’s Genocide of Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank is erasing their civilization’s 5000-year history in real-time before our eyes.

“Every country was put on notice by the ICJ that there was a plausible risk of genocide in Gaza.. every country became obliged under the law.. not to speak fine words, to take action to prevent genocide.. that obligation was activated on 24th Jan 2024”

Chris Sidoti spells it out pic.twitter.com/ruzBoXHpac

— Saul Staniforth (@SaulStaniforth) September 16, 2025

End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture

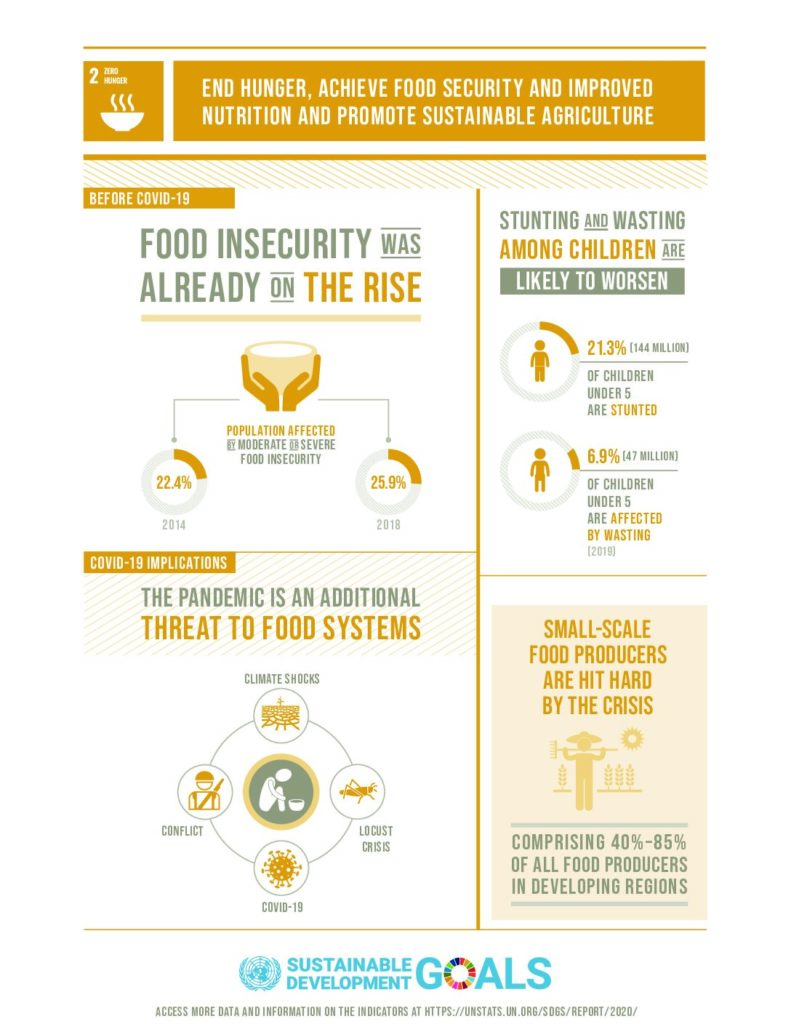

Global hunger has risen sharply since 2019 and remains persistently high. Nearly 1 in 11 people worldwide faced hunger in 2023, while more than 2 billion experienced moderate to severe food insecurity. Millions of children and women are affected by malnutrition. War is the primary driver of hunger; war may have always been, but now it is exacerbated by climate change and COVID-19.

The increasingly toxic nature of global geopolitics is evident in the triangular relationship among China, Russia, and the United States, and their respective allies (Smith 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021). This international context is not conducive to cooperation or conflict mediation.

Pressures on global food prices ease, but they remain triple pre-pandemic levels

In 2023, approximately 50 per cent of countries experienced moderately to abnormally high food prices; this is a moderate decline from 2022’s record of 60 per cent, but it is three times the 2015–2019 average of 16 per cent. This decrease was driven mainly by reductions in shipping costs and in fuel and fertilizer prices, particularly during the first half of 2023.

While most regions experienced price improvements, Eastern and South-Eastern Asia saw the proportion of countries with high food prices double in 2023, returning to 2020 levels. Rising rice prices fueled this amid weather-related production concerns, stockpiling, and trade restrictions. SIDS also saw food-price pressures worsen for a second consecutive year in 2023, driven by persistent inflation.

The number of countries in which food prices are moderately to abnormally high remains well above pre-pandemic levels. Getting progress on track with respect to Goal 2 requires urgent action to strengthen food systems, support small-scale producers, improve services, and ensure access to affordable, healthy diets. Transitioning food systems to be more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient will drive progress toward the Goals. The United Nations Food Systems Summit and its biennial stocktakes – the next of which is scheduled for July 2025 – have helped align global efforts with nationally defined priorities.

Target 2.1 – Hunger affected 9.1 per cent of the global population in 2023, up from 7.5 per cent in 2019 (between 713 million and 757 million people globally and one in five in Africa). Nearly 2.33 billion people, or almost 3 in 10, faced moderate or severe food insecurity in 2023, up by 383 million from 2019.

Target 2.2 – The global prevalence of stunting in children under the age of 5 declined from 26.4 per cent in 2012 to 23.2 per cent in 2024, but recent data indicate a potential reversal of the trend. More than 150 million children were stunted in 2024. The prevalence of overweight in children rose from 5.3 to 5.5 per cent between 2012 and 2024, though the number of overweight children declined from 36.3 million to 35.5 million. The prevalence of wasting in children declined from 7.4 per cent in 2012 to 6.6 per cent in 2024, and the number of children affected declined from 50.9 million to 42.8 million.

Some 34 per cent of children aged 6-23 months achieved minimum dietary diversity between 2015 and 2022, a slight improvement from 28 per cent in 2009–2016. Only 65 per cent of women of childbearing age achieved minimum dietary diversity between 2019 and 2023. 30.

Little improvement has been seen since 2012 with respect to anaemia, which affected one in three women between the ages of 15 and 49 years in 2023.

Target 2.3 – In most countries for which data are available, the annual income of small-scale producers from agriculture is $1,500 (constant 2017 purchasing power parity), which is often less than half of what larger producers earn. Target 2. a 32. Global public expenditures reached $38 trillion in 2023, or 36 per cent of global GDP, of which a record $701 billion was spent on agriculture. Nonetheless, agriculture represented only 1.85 per cent of total government expenditure.

Target 2.c – In 2023, the proportion of countries in which food prices were moderately to abnormally high declined to about 50 per cent. This was lower than the 61 per cent recorded in 2022 but still three times the average of 16 per cent for the period 2015 –2019.

First published on December 2, 2023. Updated December 2. 2024 and December 2. 2025.

Since 2011, Yemen has been in a state of political crisis, starting with street protests against poverty, unemployment, corruption, and President Saleh’s plan to amend Yemen’s constitution and eliminate the presidential term limit.[19]

The constitutionally stated capital and largest city is the city of Sanaa, which has been under Houthi rebel control since February 2015, as well as Aden, which is controlled by the Southern Transitional Council since 2018. Its executive administration resides in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. In 2019, the United Nations reported that Yemen is the country with the most people in need of humanitarian aid, about 24 million people, or 85% of its population.[36] As of 2020, the country is ranked highest in the Fragile State Index,[37] second-worst in the Global Hunger Index, surpassed only by the Central African Republic,[37] and has the lowest Human Development Index among non-African countries.

World Food Programme

Aiming to feed nearly 13 million of the most vulnerable people each month, WFP’s emergency response in Yemen is our largest anywhere in the world. The current level of hunger in Yemen is unprecedented and is causing severe hardship for millions of people. Despite ongoing humanitarian assistance, 16.2 million Yemenis are food insecure. Pockets of famine-like conditions have returned to Yemen for the first time in two years in Hajjah, Amran, and Al Jawf, where nearly 50,000 people are living in famine-like conditions. Over 5 million people in Yemen are on the brink of famine as the conflict and economic decline have left families struggling to find enough food to get through the day.

The rate of child malnutrition is one of the highest in the world, and the nutrition situation continues to deteriorate. A recent survey found that almost one-third of families have dietary gaps and rarely consume foods such as pulses, vegetables, fruit, dairy products, or meat. Malnutrition rates among women and children in Yemen remain among the highest in the world, with 1.2 million pregnant or breastfeeding women and 2.3 million children under 5 requiring treatment for acute malnutrition.

Total global military expenditure reached $2443 billion in 2023, an increase of 6.8 percent in real terms from 2022. This was the steepest year-on-year increase since 2009. The 10 largest spenders in 2023—led by the United States, China and Russia—all increased their military spending, according to new data on global military spending. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), available at www.sipri.org

Russian President Vladimir Putin approved budget plans that raise military spending for 2025 to record levels. Approximately 32.5% of the budget, posted on a government website on Sunday, has been allocated for national defense, amounting to 13.5 trillion rubles (over $145 billion). This is an increase from the reported 28.3% allocated this year, according to AP.

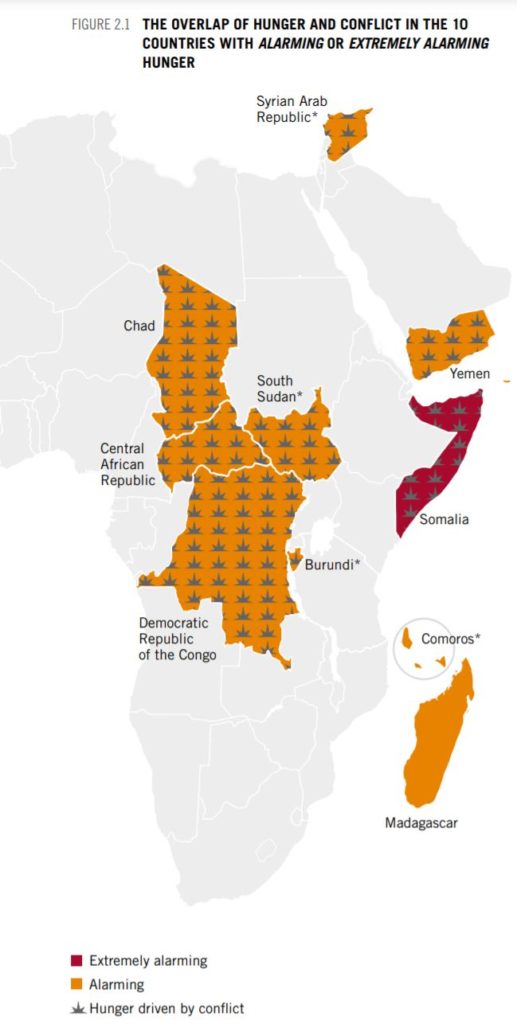

Hunger and food systems in conflict settings

Caroline Delgado and Dan Smith, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

- The number of active violent conflicts is on the rise. Violent conflict remains the main driver of hunger, exacerbated by climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Food systems in conflict-affected countries are often characterized by a high level of informality, structural weakness, and vulnerability to shocks.

- Without achieving food security, it will be difficult to build sustainable peace, and without peace the likelihood of ending global hunger is minimal.

- The two-way links between conflict and increased food insecurity and between peace and sustainable food security are unique to each case and often complex.

- The good news is that it is possible to begin to break the destructive links between conflict and hunger in the midst of ongoing conflict. Even where there is extreme vulnerability, it is possible to start building resilience.

- Breaking the links between conflict and hunger and harnessing the potential of food systems to contribute to peace will demand good contextual evidence, well-grounded knowledge of the setting, and cooperation between peace, humanitarian, and development actors.

- To integrate a peace-building lens into the creation of resilient food

systems and a food security lens into peacebuilding, we propose

four priorities:

- a flexible and agile approach that reflects local perceptions,

aspirations, and concerns; - an emphasis on working in partnerships that bring together local,

national and international actors, with their diverse knowledge; - integrative work through hubs that convene key actors and

build coalitions inclusive enough to advance peace and food

security; and - commitment by major donors to get funds out of separate siloes

and focus them on integrative work.

Violent conflict is increasing

As a general proposition, peace is more likely to be built and sustained if it is linked to secure livelihoods and food security, and vice versa (Vos et al. 2020). Yet current global, regional, and national trends are discouraging and threatening the achievement of Zero Hunger and other SDG ambitions by 2030.

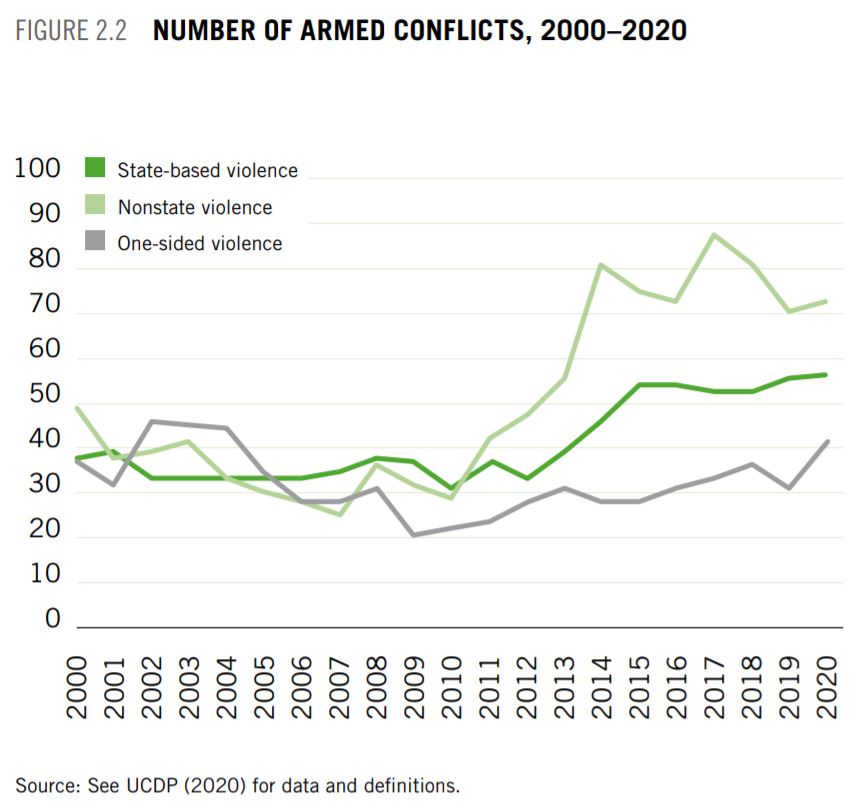

Global security has deteriorated significantly since 2010. In 2020, worldwide, there were 56 armed conflicts involving states, either in conflict with other states or with rebel forces; 72 violent conflicts in which states were not involved (nonstate); and a further 41 in which the state or a rebel force was the only actor and its opponents were unarmed (UCDP 2020; Figure 2.2).

All three forms of conflict have risen significantly in the past decade, with nonstate conflicts alone increasing by 148 percent. By 2020, military spending had risen to its highest level since before the end of the Cold War, as had the international trade in major weapons (Wezeman et al. 2020).

United Nations Global Goals for Sustainable Development

Goal 2 is about creating a world free of hunger by 2030. The global issue of hunger and food insecurity has shown an alarming increase since 2015, a trend exacerbated by a combination of factors, including the pandemic, conflict, climate change, and deepening inequalities.

By 2022, approximately 735 million people—or 9.2% of the world’s population—were in a state of chronic hunger, a staggering rise compared to 2019. This data underscores the severity of the situation, revealing a growing crisis.

In addition, an estimated 2.4 billion people faced moderate to severe food insecurity in 2022. This classification signifies their lack of access to sufficient nourishment. This number escalated by an alarming 391 million people compared to 2019.

The persistent surge in hunger and food insecurity, fueled by a complex interplay of factors, demands immediate attention and coordinated global efforts to alleviate this critical humanitarian challenge.

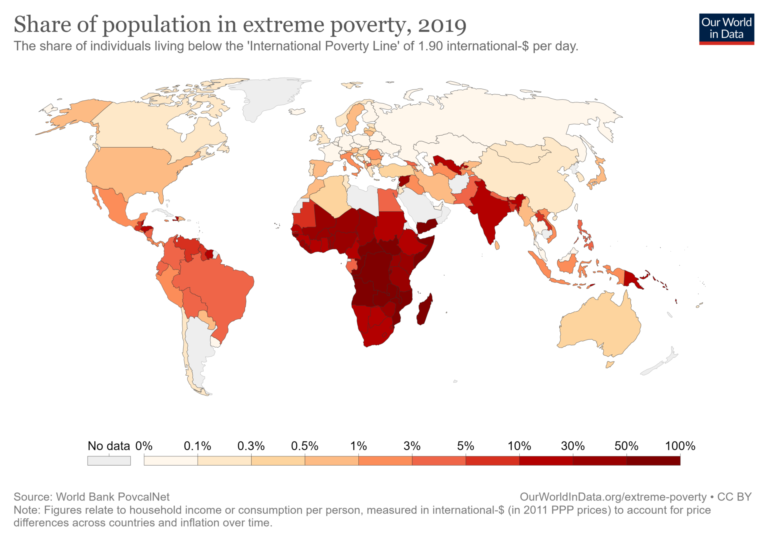

Extreme hunger and malnutrition remain a barrier to sustainable development and create a trap from which people cannot easily escape. Hunger and malnutrition mean less productive individuals, who are more prone to disease and thus often unable to earn more and improve their livelihoods.

2 billion people in the world do not regularly have access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food. In 2022, 148 million children had stunted growth, and 45 million children under the age of 5 were affected by wasting.

How many people are hungry?

It is projected that more than 600 million people worldwide will face hunger in 2030, highlighting the immense challenge of achieving the zero hunger target.

People experiencing moderate food insecurity are typically unable to eat a healthy, balanced diet regularly because of income or other resource constraints.

Why are there so many hungry people?

Shockingly, the world is back at the level of hunger that had not been seen since 2005, and food prices remain higher in more countries than in the period 2015–2019. Along with conflict, climate shocks, and rising cost of living, civil insecurity and declining food production have all contributed to food scarcity and high food prices.

Investment in the agriculture sector is critical for reducing hunger and poverty, improving food security, creating employment, and building resilience to disasters and shocks.

End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture

The UN explains: “It is time to rethink how we grow, share, and consume our food.

If done right, agriculture, forestry, and fisheries can provide nutritious food for all and generate decent incomes while supporting people-centered rural development and protecting the environment.

Our soils, freshwater, oceans, forests, and biodiversity are being rapidly degraded. Climate change is putting even more pressure on the resources we depend on, increasing risks associated with disasters such as droughts and floods. Many rural women and men can no longer make ends meet on their land, forcing them to migrate to cities for opportunities.

A profound change in the global food and agriculture system is needed to nourish today’s 815 million hungry people and the additional 2 billion expected by 2050.

The food and agriculture sector offers key development solutions and is central to eradicating hunger and poverty.”

COVID-19 response

The World Food Programme’s food assistance program provides a critical lifeline to 87 million vulnerable people worldwide. Their analysis of the pandemic’s economic and food security implications outlines the potential impact of COVID-19 on the world’s poorest people.

In light of the pandemic’s effects on the food and agricultural sector, prompt measures are needed to ensure that food supply chains are kept alive to mitigate the risk of large shocks that considerably impact everybody, especially the poor and the most vulnerable.

To address these risks, the Food and Agriculture Organization urges countries to:

- Meet the immediate food needs of their vulnerable populations,

- Boost social protection programs,

- Keep global food trade going,

- Keep the domestic supply chain gears moving, and

- Support smallholder farmers’ ability to increase food production.

The UN’s Global Humanitarian Response Plan lays out steps to fight the virus in the world’s poorest countries and address the needs of the most vulnerable people, including those facing food insecurity.

Facts and Figures

- Current estimates are that nearly 690 million people are hungry, or 8.9 percent of the world’s population—up by 10 million people in one year and by nearly 60 million in five years.

- The majority of the world’s undernourished – 381 million – are still found in Asia. More than 250 million live in Africa, where the number of undernourished is growing faster than anywhere in the world.

- In 2019, close to 750 million—or nearly one in ten people worldwide—were exposed to severe levels of food insecurity.

- In 2019, an estimated 2 billion people worldwide did not have regular access to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food.

- If recent trends continue, the number of people affected by hunger will surpass 840 million by 2030, or 9.8 percent of the global population.

- 144 million children under age 5 were affected by stunting in 2019, with three-quarters living in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

- In 2019, 6.9 percent (or 47 million) children under 5 were affected by wasting, or acute undernutrition, a condition caused by limited nutrient intake and infection.

Goal 2 Targets

2.1 By 2030, end hunger and ensure access by all people, particularly the poor and people in vulnerable situations, including infants, to safe, nutritious, and sufficient food all year round.

2.2 By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women, and older persons.

2.3 By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists, and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources, and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment.

2.4 By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, help maintain ecosystems, strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding, and other disasters, and progressively improve land and soil quality.

2.5 By 2020, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants, and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional, and international levels, and promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed.

2.A Increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development, and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular, least developed countries.

2.B Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets, including through the parallel elimination of all forms of agricultural export subsidies and all export measures with equivalent effect, in accordance with the mandate of the Doha Development Round.

2.C Adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and their derivatives and facilitate timely access to market information, including on food reserves, in order to help limit extreme food price volatility.

SDG INDICATOR 2.2.1 is the prevalence of stunting among children under 5 years of age

Stunting represents severe malnutrition as is apparent when a child has too low height-for-age. A child is stunted when their height-for-age is 2 or more standard deviations below the median of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards.

Goal: By 2030 end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age

.

The intermediate target is a reduction in the prevalence of stunting by 40% by 2025 (from 2012 levels).

Links

International Fund for Agricultural Development

Food and Agriculture Organization

Think.Eat.Save. Reduce your foodprint.

Comments are closed.