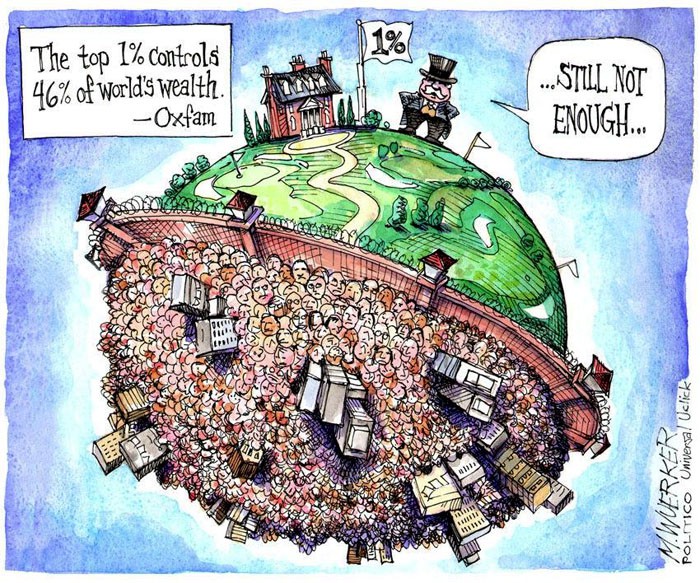

Our world’s deepest pockets — “ultra-high net worth individuals” — hold an astoundingly disproportionate share of global wealth.

Inequality has been on the rise across the globe for several decades. Some countries have reduced the number of people living in extreme poverty. But economic gaps have continued to grow as the very richest amass unprecedented levels of wealth. Among industrial nations, the United States is by far the most top-heavy, with much greater shares of national wealth and income going to the richest 1 percent than any other country.

Covid-19 and Global Inequality

Global Wealth Inequality

Global Income Inequality

U.S. Wealth Concentration Versus Other Countries

I tilfelle nokon lurar på kva gruppe dei tilhøyrer: Dei 1% rikaste eig meir enn 1 mill USD, dei 10% rikaste meir enn 100 000 USD, og dei 50% rikaste meir enn 10 000 USD. Kvar av oss “eig” i dag 260 000 USD i Statens pensjonsfond utland (oljefondet). https://t.co/I4hM2osuxu https://t.co/KAyQLt3x5G

— Tore Furevik (@ToreFurevik) November 10, 2021

Covid-19 and Global Inequality

The vaccine rollout around the globe has been rife with inequality. According to research by the Agence France-Presse, high-income nations — such as the United States and members of the European Union — have been getting much more than their fair share of vaccine doses. Despite making up only 16 percent of the global population, people in high-income nations have gotten 47 percent of all vaccine doses. That is in contrast to people in lower-income nations, who have gotten just 0.2 percent of all vaccine doses, despite making up 9 percent of the world’s population. Extreme pandemic disparities are not unique to the United States. Oxfam reports that from March 18 to the end of 2020, global billionaire wealth increased by $3.9 trillion. By contrast, global workers’ combined earnings fell by $3.7 trillion, according to the International Labour Organization, as millions lost their jobs around the world.

Global Wealth Inequality

According to the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report, the world’s richest 1 percent, those with more than $1 million, own 43.4 percent of the world’s wealth. Their data also shows that adults with less than $10,000 in wealth make up 53.6 percent of the world’s population but hold just 1.4 percent of global wealth. Individuals owning over $100,000 in assets make up 12.4 percent of the global population but own 83.9 percent of global wealth. Credit Suisse defines “wealth” as the value of a household’s financial assets plus real assets (principally housing), minus their debts.

“Ultra-high net worth individuals” — the wealth management industry’s term for people worth more than $30 million — hold an astoundingly disproportionate share of global wealth. These wealth owners held 6.2 percent of total global wealth, yet represent only a tiny fraction (0.002%) of the world population, based on Institute for Policy Studies analysis of Capgemini and Credit Suisse wealth data and Census Bureau population estimates.

The world’s 10 richest billionaires, according to Forbes, own an astonishing $1.144 trillion in combined wealth, a sum greater than the total goods and services most nations produce on an annual basis, according to the World Bank. The globe is home to 2,755 billionaires, according to the 2021 Forbes ranking.

Those with extreme wealth have often accumulated their fortunes on the backs of people around the world who work for poor wages and under dangerous conditions. According to Oxfam, the wealth divide between the global billionaires and the bottom half of humanity is steadily growing. Between 2009 and 2018, the number of billionaires it took to equal the wealth of the world’s poorest 50 percent fell from 380 to 26.

Capgemini defines a “high net worth individual” as someone with at least $1 million in investment assets (not including their primary residence and consumer goods). The total number of high net worth individuals was more than 19 million in 2019. The vast bulk of them holds less than $5 million in assets. The Capgemini annual report shows that the top tier of these wealthy individuals, those with at least $30 million, expanded significantly in 2019 after they dipped slightly in 2018 because of a downturn in equity markets.

The Capgemini World Wealth Report shows that individuals with between $1 million and $5 million in investment assets make up the largest share of world millionaires. But those with more than $5 million hold a large majority (56.2 percent) of world millionaire wealth.

Global Income Inequality

Since 1980, the World Inequality Report data shows that the share of national income going to the richest 1 percent has increased rapidly in North America (defined here as the United States and Canada), China, India, and Russia, and more moderately in Europe. World Inequality Lab researchers note that this period coincides with the rollback in these countries and regions of various post-World War II policies aimed at narrowing economic divides. By contrast, they point out, countries and regions that did not experience a post-war egalitarian regime, such as the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and Brazil, have had relatively stable, but extremely high levels of inequality.

Rapid economic growth in Asia (particularly China and India) has lifted many people out of extreme poverty. But the global richest 1 percent has reaped a much greater share of the economic gains, according to the World Inequality Report. Although their share of global income has declined somewhat since the 2008 financial crisis, at more than 20 percent it is still much higher than their 16 percent share in 1980.

U.S. Wealth Concentration Versus Other Countries

OECD statistics show that the top 1 percent in the United States holds 42.5 percent of national wealth, a far greater share than in other OECD countries. In no other industrial nation does the richest 1 percent own more than 28 percent of their country’s wealth.KKK

The United States dominates the global population of high net worth individuals, with over 5.9 million individuals owning at least $1 million in financial assets (not including their primary residence or consumer goods), as calculated in Capgemini’s World Wealth Report.

China has had the most rapid growth in the share of world millionaires, nearly doubling from 5 percent of the global total in 2017 to 9.5 percent in 2019. But 62 percent of the world’s millionaires continue to reside in Europe or North America, with almost 40 percent of these millionaires calling the United States home, according to the Global Wealth Report.

The United States is home to more than twice as many adults with at least $50 million in assets as the next five nations with the most super-rich combined. China is rising rapidly up the ranks, with the number of individuals in the $50 million club rising from 9,555 to 21,087 between 2017 and 2020, as Global Wealth Report data shows.

The United States has more wealth than any other nation. But America’s top-heavy distribution of wealth leaves typical American adults with far less wealth than their counterparts in other industrial nations, according to the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report.

Updated December 10.2024 & December 10. 2023 (originally published December 10. 2021)

United Nations Global Goals for Sustainable Development

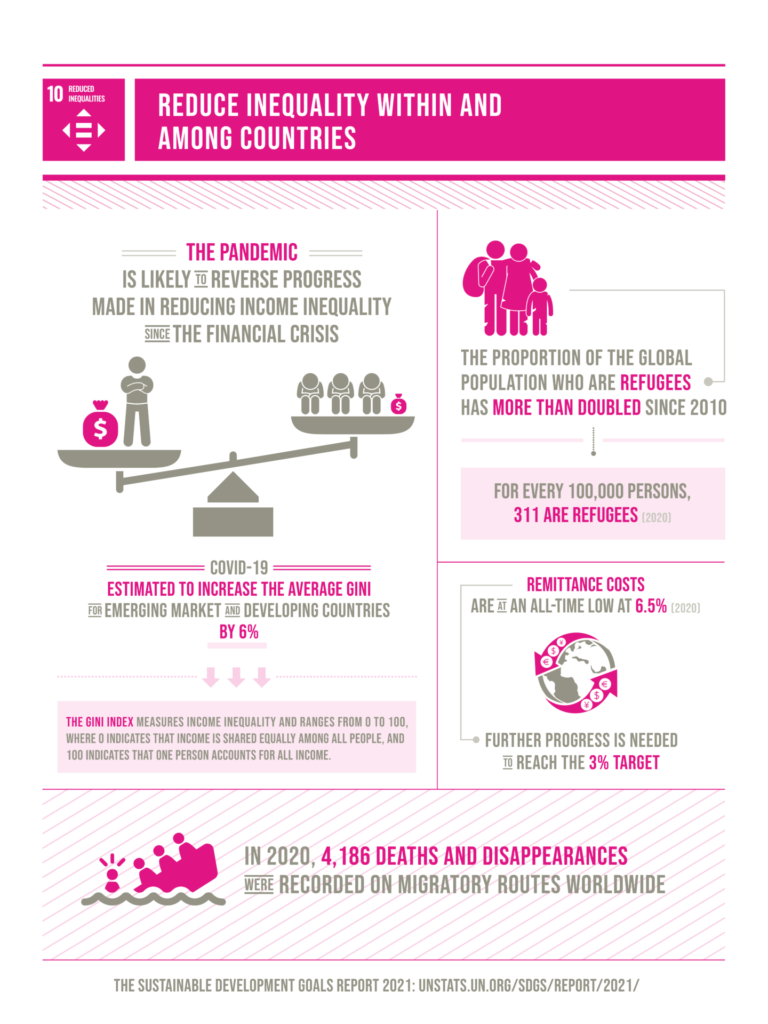

Goal 10: Reduce inequality within and among countries

Inequality threatens long-term social and economic development, harms poverty reduction, and destroys people’s sense of fulfillment and self-worth.

In most countries, the incomes of the poorest 40 percent of the population have been growing faster than the national average. However, emerging yet inconclusive evidence suggests that COVID-19 may have dented this positive trend of falling within-country inequality.

The pandemic has caused the most significant rise in between-country inequality in three decades. Reducing both within- and between-country inequality requires equitable resource distribution, investing in education and skills development, implementing social protection measures, combating discrimination, supporting marginalized groups, and fostering international cooperation for fair trade and financial systems.

Why do we need to reduce inequalities?

Inequalities based on income, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, race, class, ethnicity, religion, and opportunity continue to persist across the world. Inequality threatens long-term social and economic development, harms poverty reduction, and destroys people’s sense of fulfillment and self-worth. This, in turn, can breed crime, disease, and environmental degradation.

We cannot achieve sustainable development and make the planet better for all if people are excluded from the chance for a better life.

What are some examples of inequality?

Women and children with a lack of access to healthcare die each day from preventable diseases such as measles and tuberculosis or in childbirth. Older persons, migrants, and refugees face a lack of opportunities and discrimination – an issue that affects every country in the world. One in five persons reported being discriminated against on at least one ground of discrimination prohibited by international human rights law.

One in six people worldwide has experienced discrimination in some form, with women and people with disabilities disproportionately affected.

Discrimination has many intersecting forms, from religion and ethnicity to gender and sexual preference, pointing to the urgent need for measures to tackle any discriminatory practices and hate speech.

COVID-19 has deepened existing inequalities, hardest hitting the poorest and most vulnerable communities. It has spotlighted economic inequalities and fragile social safety nets that leave vulnerable communities to bear the brunt of the crisis. At the same time, social, political, and economic inequalities have amplified the impacts of the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly increased global unemployment and dramatically slashed workers’ incomes. COVID-19 also puts at risk the limited progress that has been made on gender equality and women’s rights over the past decades. Across every sphere, from health to the economy, security to social protection, the impacts of COVID-19 are exacerbated for women and girls simply by their sex.

Inequalities also deepen for vulnerable populations in countries with weaker health systems and those facing existing humanitarian crises. Refugees and migrants, as well as indigenous peoples, older persons, people with disabilities, and children, are particularly at risk of being left behind. And hate speech targeting vulnerable groups is rising.

COVID-19 response

COVID-19 is challenging global health systems and testing our common humanity. The UN Secretary-General called for solidarity with the world’s poorest and most vulnerable, who need urgent support in responding to the worst economic and social crisis in generations. “Now is the time to stand by our commitment to leave no one behind,” the Secretary-General said.

To ensure that people everywhere have access to essential services and social protection, the UN has called for an extraordinary scale-up of international support and political commitment, including funding through the UN COVID-19 Response and Recovery Fund, which aims to support low—and middle-income countries and vulnerable groups that are disproportionately bearing the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic.

This crisis must also be used as an opportunity to invest in policies and institutions that can turn the tide on inequality. Leveraging a moment when policies and social norms may be more malleable than during normal times, bold steps that address the inequalities that this crisis has exposed can steer the world back on track towards the Sustainable Development Goals.

Facts and Figures

- Evidence from developing countries shows that children in the poorest 20 percent of the population are still up to three times more likely to die before their fifth birthday than children in the wealthiest quintiles.

- Social protection has been significantly extended globally, yet persons with disabilities are up to five times more likely than average to incur catastrophic health expenditures.

- Despite overall declines in maternal mortality in most developing countries, women in rural areas are still up to three times more likely to die while giving birth than women living in urban centers.

- Up to 30 percent of income inequality is due to inequality within households, including between women and men. Women are also more likely than men to live below 50 percent of the median income.

- Of the one billion population of persons with disabilities, 80 percent live in developing countries.

- One in ten children is a child with a disability.

- Only 28 percent of persons with significant disabilities have access to disability benefits globally, and only 1per cent in low-income countries.

Goal 10 Targets

10.1 By 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 percent of the population at a rate higher than the national average

10.2 By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic, and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion, or economic or other status

10.3 Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies, and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies, and action in this regard

10.4 Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage, and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality

10.5 Improve the regulation and monitoring of global financial markets and institutions and strengthen the implementation of such regulations

10.6 Ensure enhanced representation and voice for developing countries in decision-making in global international economic and financial institutions in order to deliver more effective, credible, accountable, and legitimate institutions

10.7 Facilitate orderly, safe, regular, and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies

10.A Implement the principle of special and differential treatment for developing countries, in particular, least developed countries, in accordance with World Trade Organization agreements

10.B Encourage official development assistance and financial flows, including foreign direct investment, to States where the need is greatest, in particular, least developed countries, African countries, small island developing States, and landlocked developing countries, in accordance with their national plans and programs

10.C By 2030, reduce to less than 3 percent the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 percent

Links

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs

Comments are closed.