Space tourism: rockets emit 100x more CO₂ per passenger than flights – imagine a whole industry

During the launch, rockets can emit between four and ten times more nitrogen oxides than Drax, the largest thermal power plant in the UK, over the same period. CO₂ emissions for the four or so tourists on a space flight will be between 50 and 100 times more than the one to three tonnes per passenger on a long-haul flight.

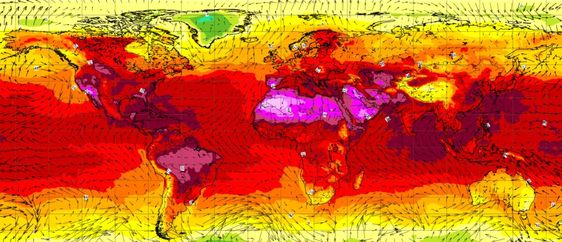

Ecocide? The aftermath of huge fires in Indonesia in 2019. Fully Handoko / EPA

Heather Alberro, Nottingham Trent University et Luigi Daniele, Nottingham Trent University

A movement of activists and legal scholars is seeking to make “ecocide” an international crime within the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC). The Stop Ecocide Foundation has put together a prestigious international panel of experts that has just proposed a new definition of the term:

If adopted by the ICC, the proposed definition would be a historic shift, paving the way for nature and other species to count legally as protected entities in their own right. However, it remains to be seen what forms of environmental destruction might still be justified if they yield sufficient social and economic benefits for humans.

An unofficial crime

The term “ecocide” was coined in 1970 by the American biologist, Arthur Galston, to designate the widespread harm caused by the US’s use of the toxic herbicide Agent Orange in the Vietnam War. Two years later, then Swedish prime minister Olof Palme described the “outrage of ecocide” in relation to the same war. But the first legal analysis and call to outlaw ecocide came from Richard Falk, a professor of international law, in 1973.

PJF Military Collection / Alamy

Yet ecocide has never been officially recognised. Indeed the Rome Statute, founding treaty of the International Criminal Court, mentions the environment just once, in relation to war crimes and only in situations legally qualifiable as armed conflicts. Beyond war crimes, the only other tool to protect the environment in the hands of the ICC is that of crimes against humanity. However, as the name suggests, this category remains deeply anthropocentric, requiring the environmental destruction to be “committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack” against a “civilian population”.

Even recent climate change litigation cases like the 2019 Urgenda case against the Dutch government frequently cite “human rights violations” in support. The movement behind the new definition, however, hopes to make ecocide its own thing – a crime of similar symbolic and normative force as genocide.

Environmental ethicist Philip Cafaro has referred to the human-induced sixth mass extinction as “interspecies genocide”. Legally, punishing genocide requires proving the perpetrator had the highest possible standard of special intent to destroy a protected human group. Ecocide, therefore, needs to be not just about protecting human groups, but protection of the biosphere.

Human-centred culture

Implementing ecocide as an international crime, therefore, would have to challenge longstanding particularly western attitudes of human separateness from, and superiority to, nature and nonhuman species, which continue to be seen as objects and resources. The concept of ecocide instead means considering nature and nonhuman species as entities with inherent value, with rights that should be respected.

Real Souls Photography / shutterstock

There are some promising developments. The groundbreaking Nonhuman Rights Project fights to secure the legal personhood and rights of nonhuman clients such as elephants, apes and dolphins across the US, while the UK government plans to introduce legislation which will recognise animals as legally sentient beings. And thanks to continued pressure from indigenous peoples, the “rights of nature” are enshrined in constitutions around the world – from India to New Zealand and Ecuador.

More clarity needed

The newly-proposed definition needs further clarification, however. For instance, it says ecocide implies “unlawful or wanton acts” very likely to cause “severe and either widespread or long-term damage” to the environment.

While “unlawful” suggests that the conduct needs to be already illegal under domestic law, it is specified that “wanton” means “reckless disregard for damage which would be clearly excessive in relation to the social and economic benefits anticipated [emphases added]”.

This implies that it is OK to damage the environment as long as the damage is not “clearly excessive” in relation to the anticipated benefits for humans. In doing so, the section reinforces the anthropocentrism that the definition itself hoped to overcome.

These benefits also include not only those of “social” character but also “economic benefits”, without explicitly excluding private profits from the equation. Finally, the test for the “wanton acts” seems to require the perpetrator, rather than the court, to judge whether or not the environmental harm was clearly disproportionate.

Towards interspecies justice

The ICC was originally set up to prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. If it adopts ecocide, could politicians and executives one day end up in the dock?

Perhaps. The new ecocide definition refers to “widespread damage” not only in a geographic sense but also damage suffered by “an entire ecosystem, species or a large group of humans”. We could potentially see action against top level executives from corporations accused of driving the mass deforestation of Indonesia to produce palm oil, threatening species like the orangutan, while leaders like Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, could potentially be prosecuted for the assault on the Amazon forest.

Prohibiting ecocide will require further mobilisations and global cooperation to ensure compliance from states not ratifying the relevant conventions, such as the US and China. Yet the movement marks a significant step towards stemming ecological and biological breakdown and establishing interspecies justice.![]()

Heather Alberro, Lecturer in Global Sustainable Development, Nottingham Trent University et Luigi Daniele, Senior Lecturer in International Humanitarian and Criminal Law, Nottingham Trent University

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.

4 Comments

Pingback: Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production - Bergensia

Pingback: bear archery

Pingback: รับทำเว็บไซต์

Pingback: เช่ารถตู้พร้อมคนขับ