Scott Schieman, University of Toronto; Alexander Wilson, University of Toronto, and Jiarui Liang, University of Toronto

Nearly half of Canadian workers feel as though the economic conditions in Canada are “poor,” according to our survey of 2,500 Canadian workers in September of 2023. And another 38 percent said they believed economic conditions are “only fair.”

These findings are unsurprising, given the poor state of the Canadian economy and the growing pessimism among Canadians toward it. Inflation and interest rates remain high, and job openings are struggling to keep up with the growing labor force.

We have tracked perceived inequality since September 2019, when we launched the first in a series of national surveys with the help of the Angus Reid Group.

We subsequently fielded similar surveys each September from 2020 to 2023, with a total of 18,500 participants in our University of Toronto Canadian Quality of Work and Economic Life Study. One goal of our study is to track long-term trends in the economic life of Canadians.

Canadians’ view of inequality

Perceived inequality is difficult to measure, so we used a well-established method researchers have used for decades in the International Social Survey Programme’s Social Inequality Module.

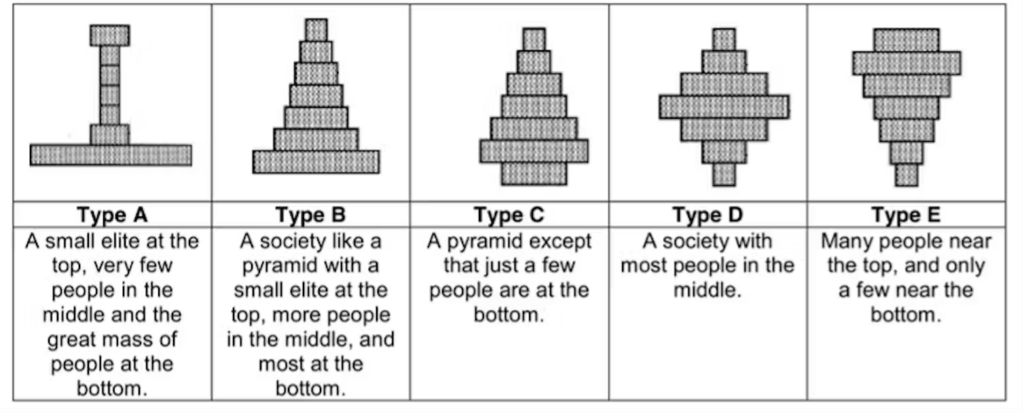

This method includes showing survey participants images and descriptions of five types of societies that each represent different levels of inequality and asking them which diagram they believe best represents their country.

In our survey, we showed respondents a diagram of the five types and asked them: “Which type of society is Canada today — which diagram comes closest?”

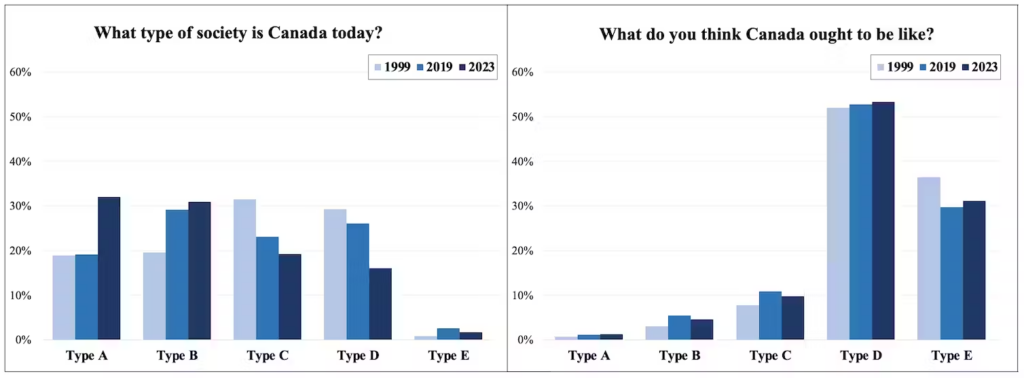

Type A represents the most extreme inequality, with a small elite at the top, few people in the middle, and most people at the bottom. Between 1999 and 2019, the International Social Survey found no change in the share of respondents — 19 percent — who believed Canada resembles Type A. But in our 2023 survey, 32 percent believed it did.

The share that saw Canada as a middle-class society (Type D) plummeted from 29 percent to 16 percent. There has been a dramatic shift in the perception of increasing inequality, with 64 percent seeing Canada as Type A or B.

When we asked participants what they think Canada should be like, 84 percent prefer a Type D or E society, where most of society are middle- or upper-class. The difference between the stability in this preferred level of inequality and the volatility of the perceived reality is noteworthy.

The cost of living and perceived inequality

The factors that shape perceived inequality are complex, but their relationship to the perceived cost of living stands out.

To measure this relationship, we asked participants: “How has your experience of the cost of living changed during the past few years?” The number of Canadian workers who said their experience was “much worse” jumped from 28 percent in 2019 to 49 percent in 2023.

“We’re so careful with our money,” a 31-year-old operations assistant told us. “Housing, food, utilities, and fuel are becoming too astronomical to handle — we shouldn’t be suffering!”

Anxiety over the cost of living can cause people to feel like economic inequality is worse than it actually is. In 2019, 27 percent of respondents who believed Canada’s cost of living was worsening viewed the country as a Type A society with a small elite at the top and most people at the bottom. Now, a whopping 41 percent do.

“Everyone I know has been cutting purchases,” a 59-year-old delivery worker said. “I haven’t purchased undergarments for five years, toiletries for three years, and I’m only able to eat one meal a day, not extras of anything.”

Canadians are disillusioned

Our discoveries support a recent report from Léger, a Canadian market research firm that found two-thirds of Canadians feel like “everything feels broken in this country right now.”

As a 37-year-old mortgage administrator said: “The country’s system is rigged in favor of the few at the expense of the many.” A 36-year-old photographer similarly said: “Our broken tax system allows folks at the top to exploit the system.”

The economy relies on worker productivity, and workers rely on the reciprocity of the economy. It’s an exchange relationship that seems increasingly compromised, as workers are being hit hardest by inflation.

Perceptions of extreme inequality undermine people’s belief that the economy is working for them. This, in turn, dampens their aspirations to improve their economic lot and weakens the hope that their efforts will translate into improved quality of life.

“Our leaders don’t do anything,” a 34-year-old personal trainer said. “I have zero faith in our political parties.” Similarly, a 47-year-old small farm owner said: “The elite of all parties rob, steal, and abuse power for personal benefit, leaving the working class to pay.”

Those in power should be concerned about the growing gap between perceived and preferred inequality. For instance, many Canadians have lost faith in the Liberal Party’s campaign promise to grow the middle class. This loss of confidence poses a threat to the Liberal Party’s chances of re-election.![]()

Scott Schieman, Professor of Sociology and Canada Research Chair, University of Toronto; Alexander Wilson, PhD Student, Department of Sociology, University of Toronto, and Jiarui Liang, Master’s Student, Department of Sociology, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.