#Wall Trump Is Never Going To Be Reagan (he campaigned to be the next Reagan).

Ronald Reagan helping in tearing down the Berlin Wall, November 9, 1989.

Ronald Reagan and Mikail Gorbachev (Perestroika and Glasnost) made this historic event happen.

#onthisday Presidential Proclamation Addressing Mass Migration Through the Southern Border of the United States

while walls of flames destroy Paradise forcing 27,000 residents to flee their homes.

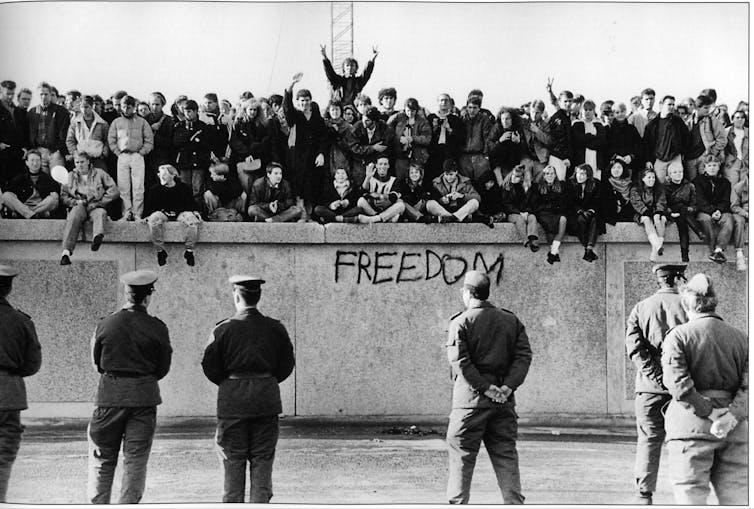

Berlin Wall, 1988. The fall of the Berlin Wall signifies the end of the Cold War and the victory of liberal democratic values. Shutterstock

Andrew Bonnell, The University of Queensland

This article is part of our series of explainers on key moments in the past 100 years of world political history. In it, our authors examine how and why an event unfolded, its impact at the time, and its relevance to politics today.

Nearly 30 years ago, in the night of November 9-10, 1989, East German border police opened the gates at crossing points in the Berlin Wall, allowing masses of East Berliners to stream through them unhindered.

This started a night of unbridled celebrations as people crossed freely back and forth through the Cold War barrier, climbed on it, and even danced and partied on it.

The signal for the mass breach of the previously heavily guarded wall was a fumbled announcement in a press conference by the Socialist Unity Party (SED) Party chief of Berlin, Günter Schabowski.

His announcement that travel restrictions for East German citizens would be lifted led to the Wall’s transit points being mobbed by thousands of East Germans as they interpreted the announcement to mean immediate freedom of movement to the West.

US Department of Defense

What happened?

The opening of the Berlin Wall triggered a series of events that led to an unexpectedly rapid unification of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG or West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (GDR, or East Germany) on October 3, 1990.

But to really understand this moment, we need to look at when and why the Berlin Wall was erected in the first place. Following Germany’s defeat in the second world war, the country was split between the victors – the Western Allies’ occupation zones became the Federal Republic in 1949, while the Soviet zone was reconstituted as the German Democratic Republic shortly thereafter.

Germany’s capital, Berlin, was also split down the middle. The wall was erected by the East German leadership in August 1961 to stop the flow of citizens from East to West, completing a sealed border that elsewhere ran along the frontier between the two German states.

The Wall’s opening was the product of two processes that had gathered momentum throughout the second half of 1989: the peaceful demonstrations and protest marches of a number of newly constituted East German civil rights organisations, and the growing number of East German citizens leaving from the GDR’s side doors.

The latter mostly happened through Hungary, which opened its border with Austria in May. Large numbers of East Germans on holidays in Hungary took advantage of the opportunity to migrate to West Germany. By November 1989, the trickle of East Germans leaving had become a flood, with thousands a day going to the West by the week the wall was opened.

Furthermore, the East German SED leadership had been increasingly on the back foot since peaceful demonstrations started, following manipulated local government elections in May 1989.

University of Minnesota Institute of Advanced Studies

By the start of October, there were regular Monday night protest marches through Leipzig and other East German cities. Initially, there were fears that the SED leadership might suppress these protests with violence.

The Tiananmen Square protests and subsequent mass killings in Beijing in June 1989 were fresh in the minds of many. But after a large-scale Monday night demonstration in Leipzig was allowed to proceed without armed opposition from the police and security services on October 9, the opposition gained courage and momentum.

A few days before the opening of the Wall, an estimated half a million protesters gathered in East Berlin’s Alexanderplatz, calling for democratic reform of East Germany.

There was, of course, a wider context for these events. By 1989, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, had become convinced of the need to carry out economic reform measures in the Soviet Union. He considered disarmament and a winding down of Cold War confrontation in Europe as necessary preconditions for such reforms.

Unlike previous Soviet leaders, Gorbachev signalled a tolerant attitude to reforms in the member states of the Warsaw Pact, including relaxation of censorship and central control of economic matters.

Indeed, Gorbachev even began to encourage the replacement of older generation communist hardliners with younger reformist leaders. When Gorbachev visited East Berlin for the official 40th anniversary celebrations of the founding of the GDR on October 7, 1989, he was rapturously welcomed by young demonstrators. They saw his visit as promising reforms that had hitherto been resisted by the ageing SED leadership under Erich Honecker.

On October 18, Honecker was obliged to step down in favour of his younger protégé Egon Krenz. However, in the following weeks, despite the almost inadvertent opening of the Berlin Wall, Krenz failed to keep up with escalating popular pressure for change.

The impact of the fall of the Berlin Wall

The new openness to reform in what was still known as the “Soviet bloc” had already seen contested elections in Poland in May 1989, and political and economic reforms in Hungary. These were catalysts for the changes in East Germany (especially events like Hungary’s opening of its western border).

In the weeks after the opening of the Berlin Wall, there was a peaceful transition to democratic government in Czechoslovakia, and less peaceful changes of régime in Romania and Bulgaria, as it became clear the Soviet Union was no longer prepared to support hard line Communist governments in Eastern Europe.

Contemporary relevance

US Department of Defense

The lasting consequences of the fall of the Berlin Wall were momentous.

Despite the presence of hundreds of thousands of Soviet army troops in the former Cold War front line state of East Germany, Gorbachev agreed in negotiations with the United States President George H. W. Bush and West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl to permit a swift unification of the two German states. This occurred almost entirely on West German terms.

The speedy collapse of the East German economy in mid-1990 left East German leaders, now democratically elected, with little leverage. Once the West German currency, the Deutsche Mark, was introduced into the East in a currency union in July 1990, East German firms, already exposed by the disintegration of the Soviet bloc, were drastically unequipped to compete.

For two centuries, modern European history had largely revolved around the “German Question”: what external borders would a German state have, and what political order would prevail in this pivotal Central European state? The peaceful and democratic unification of 1990 seemed to provide a definitive answer.

Providing real unity between West and East Germans required massive financial transfers from West to East. The transformation of the Eastern states in practise caused significant economic and social dislocation. As East Germans made enormous adjustments in their lives, their Western cousins were also paying slightly higher taxes to cover the costs of unification.

More globally, the fall of the Berlin Wall marked the symbolic end of the Cold War. Berlin had long been a cockpit of Cold War confrontation – now it was the victors’ trophy. One US policy analyst prematurely proclaimed the “end of history”, in so far as history was a clash between major political orders, and Western democracy and capitalism had won.

But since 1989, many disappointments have followed the initial euphoria. The “peace dividend” hoped for by millions, and Gorbachev’s sunny but characteristically vague formula of peaceful coexistence in a “common European home”, have not eventuated. Instead, a triumphant NATO has pitched its tents inside the borders of the old USSR, and a surly and resentful Russia has responded with brinkmanship and confrontation.

Following the end of the Cold War, neoconservative US administrations sought to put their stamp on the world, and the “blowback” has resulted in chaos in much of the Middle East and think tank predictions of a “clash between civilizations”.

Economically, turbocharged neoliberal capitalism has come under question, especially following the 2008 global financial crisis. But, what is significant to note is that since the collapse of state socialism, symbolised by the fall of the Wall, the contours of an alternative social order have become almost impossible to discern.![]()

Andrew Bonnell, Associate Professor of History, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

24 Comments

Pingback: ซิเดกร้า

Pingback: หวยแม่โขง

Pingback: เลสิค

Pingback: บัตร psn

Pingback: บริษัทกำจัดปลวก

Pingback: https://www.greatbistro.hu/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/19914.html

Pingback: slot gacor hari ini

Pingback: Event venue phuket

Pingback: https://hitclub.blue

Pingback: บาคาร่า สด แทงฟินทุกค่ายเล่นได้ 24 ชม.

Pingback: happyluke

Pingback: ทางเข้าpg

Pingback: สล็อตค่ายนอกแตกดี ลิขสิทธิ์แท้

Pingback: Huaylike VS LSM99 แทงหวยออนไลน์

Pingback: ทางเข้าpg168

Pingback: คลินิกเสริมความงาม

Pingback: นักสืบ

Pingback: ตรวจหวยย้อนหลัง LSM99

Pingback: โอลี่แฟน

Pingback: Mostbet

Pingback: som777 อะไรให้เล่นอีกบ้าง ?

Pingback: fortune ox

Pingback: เกม Y8

Pingback: หวยลาว