By Ken Grady at The Upside News

I don’t really want to review this film.

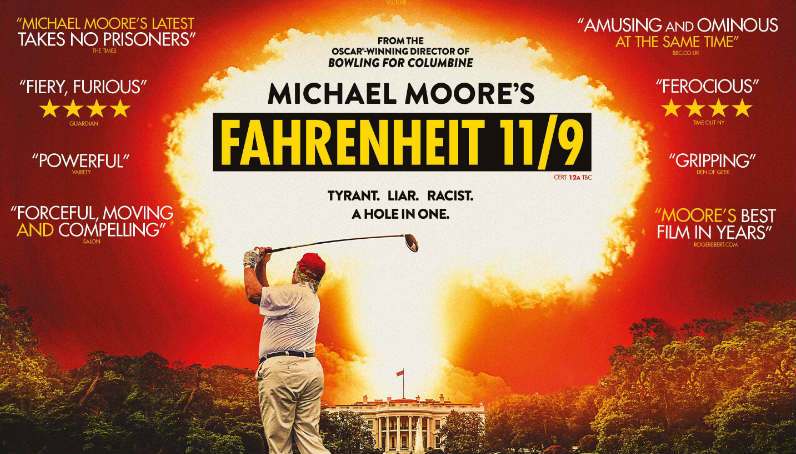

Not because this film isn’t another engrossing Michael Moore documentary, because it is. But because, after viewing it, I have to face up to the fact that my worst fears are more than likely an underestimation of the current bleak state of play in American and world politics.

The conclusion that this film draws is that, for the foreseeable future, at least, we are all right royally (or should that be ‘presidentially?) screwed.

Moore’s film is wide-ranging in its selection of examples from American life that have been utilised to expose the depth of the problem. Moore is also upfront in declaring his intention to emotionally manipulate his audience in order to encourage our action over our complacency. It is, Moore clearly asserts, obviously a matter of some urgency that we act to bring about change. There is no time left for subtlety.

Donald Trump’s son in law, Jared Kushner, in a clip used in the film, states: ‘[You] might not always agree with his politics, but Moore’s a good film-maker. He really knows how to build and convey a compelling argument.’ The quality of Moore’s earlier films undoubtedly suggests that Kushner’s assessment is hard to refute.

But Moore’s skill in constructing an argument, however, is stretched to its limit in his latest film. He tries to simultaneously cover so many of the spot fires burning in America, that he struggles to successfully draw everything together with any sense of satisfactory cohesion by the film’s end. This does, perhaps, from one perspective serve to suggest that it is getting harder and harder to keep any sense of clear perspective on these events as they continue to escalate and multiply.

And this, however, may be Moore’s point – that he is showing us all, and his fellow Americans specifically, that the time for action is now. Nothing can neatly be kept under control any longer, as the way of life we have all blindly defended for generations is exponentially fragmenting and decaying at a faster and faster rate while we procrastinate.

No-one else can be called upon to come to our rescue. We must all do something to bring about a sudden and necessary change ourselves – and, as Moore continually strives to show us, we must do it now.

More than anything this film seems to be a thinly veiled call to revolution.

Moore does, at times, fall back on some old tried and true ‘comic’ tricks here, such as trying to unsuccessfully affect a house arrest of the Governor Of Michigan, Rick Snyder, for poisoning the entire population of the city of Flint, but the familiarity of his approach does not diminish the seriousness of the point he makes about this tragedy in any way.

Moore, in his films, often plays to what we already know – primarily, things are, despite what we are being told, really bad – but here he deftly builds an even more depressingly clear picture of the extent of corruption in our political world. And most tellingly, he powerfully strips away all those too easily accepted lies that continue to constantly reinforce America’s depiction as being a ‘democracy’ and the ‘land of the free’.

We may have already been aware of a lot of the broad strokes of his central argument, but it is the detail here, in the graphic depiction of the human cost of these biased policies of greed that legislate actions so far removed from any right-minded person’s moral outlook would tolerate, that will shock viewers the most.

No former President, or Presidential candidate, is spared Moore’s flaying. Not even Barack Obama who has been held up as the current President’s polar moral opposite so often in recent times.

Drawing together decisions made by former Presidents from both major parties during their terms in power, Moore has made it easy for us to see how such an aberration as Donald Trump is elevated to the Oval Office.

We are shown the cumulative effect of the equivocations and betrayals perpetrated by former leaders and how these became the catalyst for disillusioned would-be voters to turn away from the ballot boxes, subsequently creating a vicious cycle of worsening outcomes for the non-privileged.

Those righteously angry non-voters, shown to be representatives of a process that keeps happening across the States time and again, who, in their intended protest through withdrawing their vote, have inadvertently invited a line of ever more narcissistic, otherwise indifferent, power addicts into the White House through the vacuum their absent votes has created for them to crawl through.

Moore does try to inculcate some degree of hope in the face of this scenario by showing us many idealistic young people who are concerned enough to act in opposition to the dominant power clique, pointedly skewing his chosen cross-section of ideologues to show that it is largely women who are now mobilising against the patriarchal ruling elite. This hope is only depicted as being faint, however, as he also seems to assert that the system, structurally, is virtually infallible and that these brave moral insurgents are doomed to be ineffectual in their efforts to bring about any realistic level of change from within it.

Fahrenheit 11/9 is an unsettling viewing experience. Hopefully, it won’t simply send all right-minded people into a deep black depression, but will instead encourage its audience to channel their anger into joining in with a collective call for change or take grassroots action to steer our world back from the brink of entering an even darker period of political insanity.

by Nathan J. Robinson at Current Affairs

Moore talks about James Comey and Vladimir Putin for about 10 seconds. His film is far more focused on issues that seem, on the surface, only tangentially related to Trump, such as the Flint water crisis and the West Virginia teachers’ strike. For Moore, the United States’ problem is not just that a morally repugnant man occupies the Oval Office. It is that the country’s political process itself has become so dysfunctional and useless that it is incapable of solving the most basic problems in ordinary people’s lives. We don’t just need to get rid of Trump. We need a politics that actually delivers for people.

The Flint water crisis is returned to repeatedly throughout the film. Here, the main villain is not Donald Trump but Michigan’s ex-CEO governor Rick Snyder. Moore draws a connection between Snyder’s promise to run the state like a business and his indifference to the contamination of a poor population’s water supply. Flint’s experience is a parable about inequality: GM managed to escape the crisis after Flint’s contaminated water was found to be corroding engine parts. The company arranged to get clean water from elsewhere, while the residents of Flint were still drinking and bathing from bottles. Moore speaks to an Iraq veteran in Flint who says that conditions in her town are worse than she saw on her tour of duty.

Viewers might wonder what the extended detour into Flint’s troubles has to do with Donald Trump. Everything, Moore says. In Michigan, Trump won by only 10,000 votes. Yet there were 80,000 people who actually showed up to cast ballots in 2016 yet left the line for president blank. There were far more who didn’t vote at all. Moore suggests that neglect has led to disenchantment, and disenchantment has made room for the rise of Trump. Moore thinks we are trapped in a downward spiral: As inequality has worsened, people have lost faith in government, and the disengagement of neglected voters in places like Flint will allow the further consolidation of power in the hands of Trumpian rich elites.

For this, Barack Obama and the Democratic Party receive a good portion of the blame. Moore singles out Obama’s handling of the Flint crisis as particularly pitiful. Obama flew into town, took a small sip of the local water, gave a speech filled with his usual reassuring platitudes, and flew out of town again.

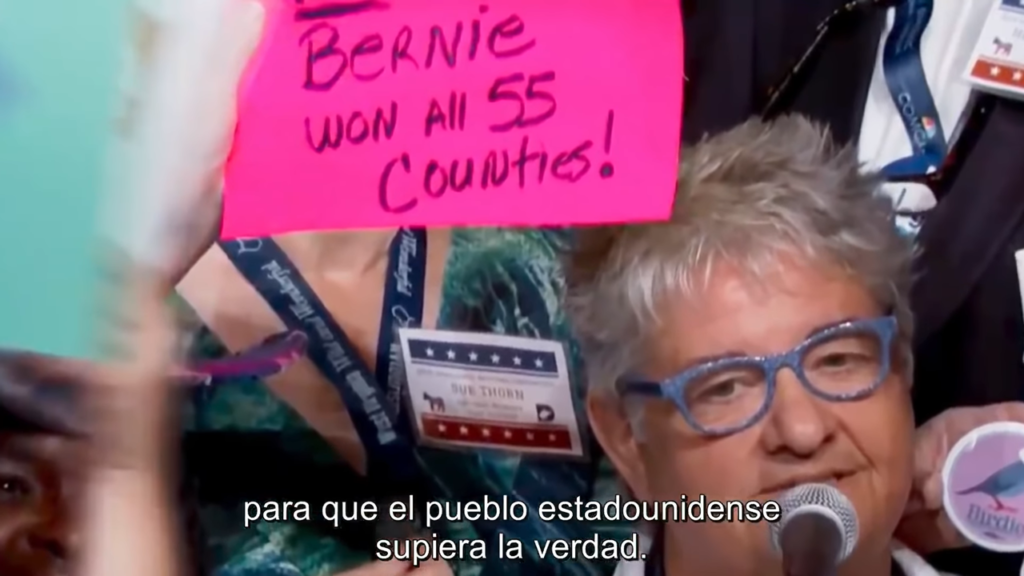

To Moore, Obama’s presidency showed the flaws in liberal politics that paved the way for Trump: Obama spoke upliftingly but failed to fight entrenched interests, taking Wall Street’s money and dithering for nearly two years before finally declaring a state of emergency in Flint. Obama’s Defense Department even used Flint, without warning, as a training ground for urban warfare exercises terrifying the residents with explosions and helicopters. Moore is scathingly critical of the way Democrats have showed contempt for the interests and preferences of working people. He points out the perversity of the “superdelegate” system in the presidential primary, which meant that in West Virginia, Hillary Clinton was awarded more delegates than Bernie Sanders even though Sanders won every single county in the state. As millennial voters have become increasingly critical of capitalism, Democratic leaders have dismissed them, worsening the prospects for a strong left opposition to austerity policies.

One of Moore’s most important points is that if the majority’s preferences were reflected in political policy, the United States would be a firmly leftist country. Most Americans support single-payer healthcare, tuition-free college, paid family leave, legalized marijuana, a path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants, and a host of other policies that have somehow been pushed to the fringes in Washington, D.C. itself. Moore points out that Democrats control almost no state governments and none of the three branches of the federal government, even though they have won the popular vote in nearly every presidential election for the past 30 years. (Funnily, the Wall Street Journal’s reviewer, who hated the film, seems to have stepped out for popcorn during this segment, since he writes “Mr. Moore is going to castigate Mrs. Clinton for her various electoral missteps—among them, devoting insufficient attention to Mr. Moore’s beloved upper Midwest—shouldn’t he mention that despite losing in the Electoral College she still won the popular vote by 3 million?”) Moore asks Democrats to face up to the obvious: They have been losing because they haven’t been doing what people want them to do, namely fight hard for left policies that will make people’s lives better. He shows a hilarious montage of Democratic Party bigwigs saying the word “compromise,” which sometimes seems to have become the party’s central policy plank.

Despite the digressions, the film is bookended with discussions of Donald Trump. At the beginning, Moore recaps Trump’s long history of bigotry, cruelty, and creepiness. He recounts familiar but still-disturbing episodes like Trump’s involvement in the Central Park Five case (in which he took out a newspaper ad calling for innocent black teenagers to be executed). Moore features a montage of Trump’s suggestive remarks about his own daughter, though weirdly he declines to remind us about Trump’s documented history of sexual assault (which seems, to me, far more damning than unfounded speculations about his relationship with a woman who has shown him full public support). Moore shows how media figures underestimated the threat he posed, and were happy to help fuel his rise if it served their ratings. (“It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” as the now-disgraced Les Moonves said.) Moore does not exempt himself here, and shows icky clips of his own friendly encounters with Trump, Jared Kushner, and Kellyanne Conway. Everyone who laughed at Trump as he became increasingly powerful, though, bears blame.

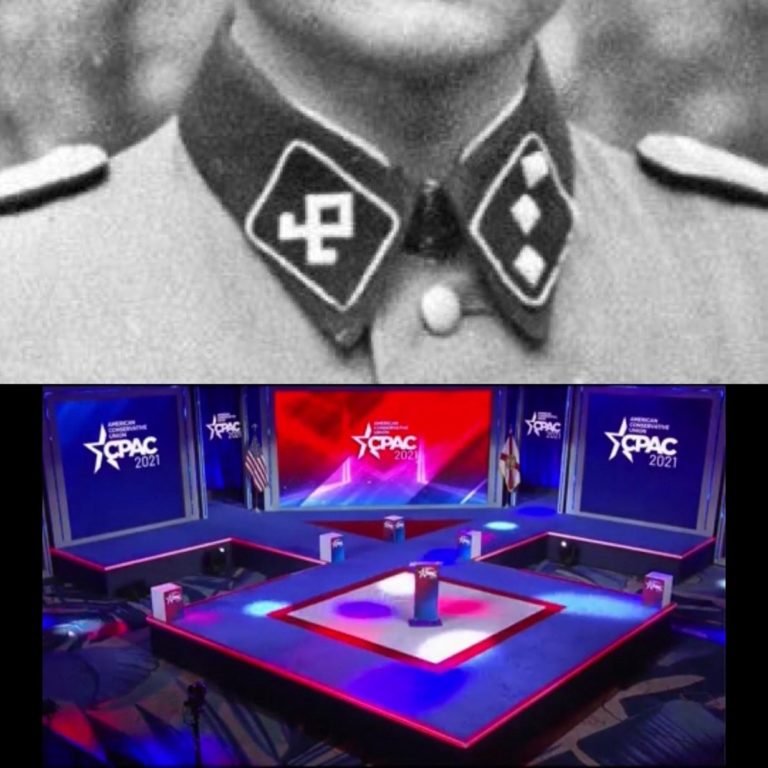

All of this has led, in Moore’s view, to a perilous political moment. Moore does not shy away from Hitler comparisons. It is not, in his view, that Trump is currently acting like Hitler at his most murderous. It is that Trump has laid the groundwork. Moore suggests that we are “one emergency away” from a dictatorship. Trump has publicly joked about becoming president for life, but Moore says these kinds of ideas, once pushed into the discourse, can become very real very fast. He does not think Trump will surrender power willingly, and worries about a “Reichstag fire” situation, in which a terrorist emergency is used as an excuse to put the country under martial law. Again, he is not saying that this is happening. He is saying that there is little to stop it from happening. Moore even cites a Jewish newspaper of the 1930s, which reassured people that Hitler was not as menacing as he seems, and repeated the familiar liberal faith that the “constitution” would ensure dictatorship never came to Germany. They were naive then, Moore says. Let’s learn the lesson. Movingly, he speaks to the last surviving Nuremberg prosecutor, who is not shy himself about drawing parallels.

To make the “Reichstag fire” situation that much more conceivable, Moore ends his film with January’s false missile alert in Hawaii. After a moving sequence showing everyone from striking teachers to Colin Kaepernick fighting back, Moore shows how it could all come unraveled in a second. BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND… THIS IS NOT A DRILL was the text received all over the state at 8:07 AM. People panicked. They jumped in holes, they ran around aimlessly, they said teary goodbyes to friends and family. The text was a mistake; there was no missile inbound. But, Moore says, what if it did happen? We live in a world where the major powers are pointing thousands of nuclear weapons at each other at all times. A slip in human judgment, a bout of insanity, could cause a calamity. And what then? In moments of crisis, when nobody quite knows what to do, power can be seized by opportunists. If you don’t fix the political system before the next moment of opportunity, Moore says, nobody knows what horror awaits. It’s an absolutely chilling ending.

As I say, I disagree with some parts of Fahrenheit 11/9’s analysis, and you wouldn’t be wrong to call it polemical, hyperbolic, and at times unclear. Some connections between events are made emotionally rather than rationally (the connection between the gun control debate and economic inequality, for instance), and Moore does not do nuance. But the film is a discussion-starter: It highlights the genuinely important topics, from the deeper causes of Trump’s rise to the neglect of poor Americans by both political parties. It is nonpartisan, and nobody can accuse Moore of shilling for the Democratic Party. It is urgent, provocative, and funny. It will probably leave you angry, and despite Moore’s general fear and hopelessness, it will also likely leave you inspired by some of the extraordinary people he has profiled. I recommend that everyone see it, think about it, and argue about it.

17 Comments

Pingback: GUILTY! GUILTY! GUILTY! GUILTY! - Bergensia

Pingback: Japanese tattoo Khao Lak

Pingback: โหลด โปรแกรมสูตร บา คา ร่า sa gaming ฟรี

Pingback: ccaps.net

Pingback: โซล่าเซลล์

Pingback: เสือมังกร lsm99

Pingback: bonanza178

Pingback: Fun88

Pingback: psychedelic mushrooms

Pingback: how to make magic mushroom tea

Pingback: ปีนผาจำลอง

Pingback: ส่งsms

Pingback: รับทำ SEO

Pingback: หอพัก

Pingback: ทรรศนะบอล

Pingback: scam site: beware do not send money or do business with this site. 100% scam!

Pingback: เว็บปั้มไลค์