Mikhail Khodorkovsky (English) @mbk_center

A leaked letter from the Russian Finance Ministry says that as of 28.8., 361.4 billion rubles have been paid to the families of the deceased

For each fallen soldier,it’s 7.4 million rubles

‼️ In total,this gives 48,759 confirmed dead

Missing and DPR + LLR soldiers are not counted pic.twitter.com/QCEuXOMFrG— Mikhail Khodorkovsky (English) (@mbk_center) September 9, 2022

2️⃣2️⃣7️⃣ days of full-scale Russia’s war on #Ukraine.

Information on #Russian invasion.

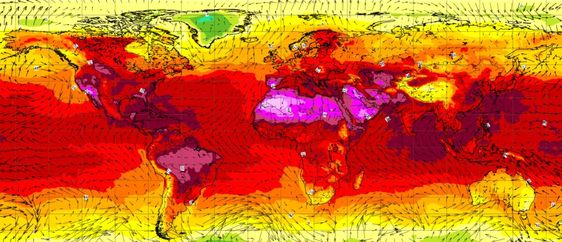

Losses of #Russia’s armed forces in Ukraine, October 8. pic.twitter.com/THjntACIyP— MFA of Ukraine 🇺🇦 (@MFA_Ukraine) October 8, 2022

Jonathan Este, The Conversation

Once it became clear – which it did early on in this conflict – that Ukraine’s defenders would not wilt before the onslaught of Vladimir Putin’s war machine, analysts predicted a long and drawn-out war of attrition, particularly in the east of the country where Russia already controlled a fair bit of territory.

And so it has proved. More than six months in, Russia controls only a fraction of the country and, close observers excepted, if you were to look at the war maps we have been publishing in these updates over the weeks, it was hard to discern much movement in the lines of occupation.

But now reports coming out of Ukraine are of sudden rapid advances by the Ukrainian army in the Kharkiv region in the north-east, where Kyiv has begun a counteroffensive that has taken the rest of the world by surprise, coming hot on the heels of the launch of a push in the Kherson region in the south. Analysts are speculating that one of the reasons Ukrainian troops are meeting less resistance around Kharkiv is that the Russian military command moved troops and equipment south to the Kherson region. We’ll have more on that next week.

The Ukraine general staff announced that more than 50,000 Russian troops had been killed since the conflict began in February. That’s a lot of grieving families. But Vladimir Putin appears to retain the support of a majority of Russians if opinion polls are to be believed.

Alexander Hill, a professor of military history at the University of Calgary, writes that the Russian leader has the support of almost all of the country’s news media (unsurprising, as he controls almost all of it). So ordinary citizens have been fed a non-stop diet of propaganda since before the invasion was launched. Meanwhile, thanks to oil and gas revenues, the economy is in reasonable shape still. And, Hill asserts, people may just be too scared to admit their opposition to the war.

Supporters of Russia are not faring so well in Ukraine’s occupied territories. According to Stephen Hall, who researches Russian politics at the University of Bath, Ukrainians who turned coats to become pro-Russian officials in Kherson and other areas under Russian control have been the targets of assassination plots, many of them successful.

Nuclear threat

There is fierce fighting in the Zaporizhzhia region, where Ukraine built Europe’s largest nuclear power plant. Recently, the power cables to the plant have been cut, leaving the plant disconnected from the electricity grid and relying on backup power to keep cooling systems operating.

There have been calls for a safety and security zone around the plant in south-eastern Ukraine to avoid a nuclear disaster. Ross Peel of King’s College, London, who specializes in nuclear safety and security, says this sort of intervention would be unprecedented – nuclear plants that have been attacked in the past have not been operational. It would also be very dangerous and legally difficult.

But, in this fascinating Q&A published by our colleagues in the US, Najmedin Meshkati, professor of engineering and international relations at the University of Southern California, explains the risks involved.

Echoes of the second world war

There is also increasing concern (and a fair bit of international outrage) at evidence suggesting that Moscow has authorized the mass deportation of Ukrainian citizens to unknown destinations in Russia. These are not prisoners of war, but perhaps as many as 1.6 million men, women, and children who – according to US secretary of state, Anthony Blinken, are being “interrogated, detained, and forcibly deported … from their homes to Russia – often to isolated regions in the far east”.

Christoph Bluth, professor of international relations and security at the University of Bradford, says this has long been a tactic used by Russia and previously by the Soviet Union before the second world war.

Bluth says this is in direct contravention of the 1949 Geneva Convention, which clearly rules mass deportations or forced relocations as a war crime.

Finally, Tim Luckhurst, a former BBC war reporter, now dean of South College at Durham University, specializes in journalism’s history and is interested in how the British press covered the second world war. He has delved into the archives to give us a flavor of how Fleet Street covered the plucky Ukrainian resistance in the face of the Nazi invasion and occupation between 1941 and 1945.

Interestingly, while the daily newspapers were happy to follow the government briefings slavishly, weekly magazines such as the Economist gave a more nuanced account in which some Ukrainian nationalists sided with the German invaders.

Jonathan Este, Associate Editor, International Affairs Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

9 Comments

Pingback: Russian losses in Ukraina "special military operation" - Bergensia

Pingback: healing meditation

Pingback: site

Pingback: astro dab pen

Pingback: Firearms For Sale

Pingback: สล็อตออนไลน์ lsm99

Pingback: caluanie muelear oxidize used for

Pingback: Banana Cream Pie Cookies for sales,

Pingback: รับเหมาไฟฟ้า