Brexit and other populist shocks are a sign that our conception of equality is broken. We need to remake it.

The UK parliament just rejected *eight* different paths forward when it comes to Brexit, including a no deal Brexit, a second referendum (rejected by a narrow margin) and a Norway+ deal with the EU. So that’s ‘no’ to Theresa May’s deal, and ‘no’ to pretty much any possible alternative to the deal.

How did we get into this mess?

I wrote this piece about how the roots of Brexit, and the populist turn more broadly, lie partly in a two-fold break in our conception of equality. Like anything I (or anyone else) writes about Brexit, I’m sure it will generate some vehement disagreement. But hey, welcome to 2019.

Author: David Mattin

Nearly three years after the June 2016 referendum, Britain’s mission to wrench itself out of the EU is finally coming to a head.

It’s been three years of political stasis and confusion. Meanwhile, every reputable forecast suggests the UK will be poorer once the mission is complete. The British government’s own forecast says that 15 years after Brexit the economy will have shrunk by between 2.5% and 9.3%. For context, the 2009 financial crisis shrunk the British economy by 6.25%.

Now, Theresa May’s failure to get her deal with the EU past parliament means Britain is weeks away from a chaotic ‘no deal’ exit: the kind that will push the country towards the economic worst case scenario. Think a sharp drop in the value of the pound, a spike in unemployment, and rocketing inflation. Searing economic pain, in other words.

But in a YouGov poll published on 22 March, 88% of those who voted Leave in June 2016 say they would do so again.

Mainstream economic theory says that should not happen. People shouldn’t choose to become materially worse off.

But those who are surprised by the resilience of support for Brexit are making a key analytical mistake. While the material conditions of the British people naturally played a key role in the Brexit vote, the underlying cause was something that runs even deeper. The vote was an angry, dysfunctional cry for the human dignity that so many in Britain feel has been denied them.

And underlying that cry is an idea at the heart of modernity. One that’s fundamental to the way we moderns relate to one another and the societies in which we live. That is, the idea that all human beings are of equal value.

The idea that all people are of equal value runs deep in contemporary liberal democracies. Indeed, the idea is now so commonplace that its easy to forget that it’s a relatively new one. Many in 19th-century slave-owning Britain thought that some human beings are inherently more valuable than others, and that idea has prevailed in almost every society in every place and time until recently. Today, however often we fail to live up to the ideal in practice, only a fringe, nano-minority would disagree with the statement, ‘all human beings are inherently of equal value’.

But in Britain, as across much of the western world, our conception of equality has become broken in two crucial ways. Both of them are relevant to the Brexit vote. They’re also relevant to much else that defines the current crisis of the liberal democratic west, including the rise of populisms across Europe and north America.

First, there is the problem of elite hypocrisy. This is a problem to do with the way we practice equality.

For 30 years, the UK’s top 10% — even more so its top 1%, even more so its top 0.1% — have hoarded the gains from economic growth. What’s more, they’ve done that while paying lip service to liberal paeans about equality, meritocracy and the rise of a ‘classless society’. Search in vain for a member of the British elites — left or right, civil servant or banker, entrepreneur or academic — who will disagree with statements such as ‘people should advance according to their merit’: you won’t find one. But very few have proven prepared to see themselves or their children live according to those principles.

It’s one thing to live in a society with wide economic inequality: that has been the fate of most people in human history. It’s another to live in such a society while its elites congratulate each other for being enlightened, virtuous meritocrats. That breeds a special kind of anger. The kind that will cause millions to want to kick their elites in the teeth, no matter the consequences.

Second, there is the problem of points of view. This is a problem to do with the way we think about equality.

One of the most profound, far-reaching changes across the western world since WWII has been the end of deference. In the decades after 1945, rising affluence, new educational opportunities and the ascent of pop culture all helped sweep away the last vestiges of traditional social structures that saw people defer to their social superiors. This change was a good thing; one that unlocked vast stores of human potential, brought us much great art, and made our societies more productive and just.

Decades on, that shift helped make the Brexit vote possible. It was, after all, a vote that saw over 17 million Britons vote for a constitutional change against the explicit recommendation of pretty much the entire British elite: government, civil service, media, business leaders, bankers and more.

But somewhere along the way, the idea that underpinned the decline of deference — that is, the idea that all people are of equal value — has mutated. The Brexit vote and its aftermath has made clear that not only do millions believe that all human beings are of equal value, they also believe that all viewpoints are of equal value.

In fact, all human beings are of equal value, but all viewpoints are not. Some viewpoints are informed, and some are not. Some are intelligent, and some are not. Some are true, and some are not.

That is a reality that has become difficult — perhaps impossible — to utter in 2019. Today, to hold the viewpoint of one person above that of another is to risk being accused of elitism, snobbery, or condescension. Instead, it sometimes feels we’ve come to believe that to perfect our democracy means to allow perfectly equal weight to the viewpoint of each citizen. The logic that underpins that sentiment is, ‘I am a person just as valuable as you, and therefore my opinion is just as valuable as yours’. But this is a broken logic, and it has bedevilled the national debate on Brexit: a debate in which points of view based on superior knowledge, experience or personal wisdom have often been treated with disdain by the court of popular opinion. (That has been true of people on both sides of the argument. But yes, the most striking example has been the unwillingness of some Leave voters to countenance informed argument on why leaving the EU is unlikely, in the end, to make them feel they’ve reclaimed dignity in the way they hope.)

This is no small problem. Indeed, it’s a problem that runs to the very heart of representative democracy, which is a system based on the idea that some viewpoints are better than others. In a representative democracy, citizens are supposed to elect people whose knowledge, experience and judgement they believe to be superior, and then allow those representatives to use that superior judgement on their behalf. When a society comes to believe that no one person’s judgement can better than another’s — indeed, that the very idea of a ‘superior judgement’ is an affront to natural human equality — then the idea that animates representative democracy starts to break down. That’s where we are at now. Witness the near-pathological contempt that many in Britain and across western democracies have for their elected representatives. It’s fuelled by an anger that screams: ‘who are you to tell me anything?’

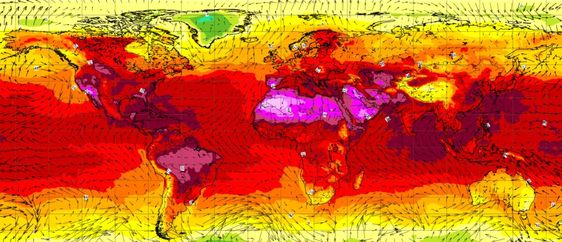

Of course, in 2019 our conception of equality is broken in other ways too: along gender lines, along racial lines, and others. But these two problems in particular — the problems of elite hypocrisy, and the problem of points of view — are central to the vote for Brexit that shocked Britain in 2016. More broadly, they’re central to the rise of populisms across Europe and north America. And to the way that western liberal democracies are dealing with (that is mostly failing to deal with) other complex issues, such as climate change and the overreach of Big Tech.

In the end, this all comes down to a set of deep and vexed questions. What is the true nature of human equality? Given that perfect economic equality is incompatible with a society in which people live freely, what duties do the economic elite owe to those who are less well off? Even more vexed: how do we acknowledge that human dignity exists equally across all people, but that valuable points of view do not? Traditional social deference was a system — albeit an extremely faulty one — for deciding which points of view society should consider valuable. In a culture in which traditional deference is long dead who gets to decide that?

Of course, the current crisis in liberal democracy is deep and complex. It can’t be summed up by this single idea, or any single idea. But follow many of the roads and you’re led to one destination: the problem of equality, what it really means, and how we should practice it.

To overcome that crisis, and to dream up whatever should come next, we need better answers to those questions.

This article was originally posted by the author on Medium, you can read the original article here.

David Mattin is Global Head of Trends & Insights at TrendWatching. He sits on the World Economic Forum’s Global Future Council on Consumption.

3 Comments

Pingback: Nearly 1.5 million young people have registered to vote for election 2019 – and more could join them - Bergensia

Pingback: The "Rebel Alliance" Heroes - Bergensia

Pingback: relax everyday