Elon Musk at the ADF Rally

Elon Musk has stated that the upcoming election in Germany “could decide the fate of Europe, maybe the fate of the world,” while expressing support for the AfD party and urging German citizens to vote for them. pic.twitter.com/YbGCIONKz5

— PitunisWorld 🌎 (@ScMesab) January 25, 2025

Laurenz Guenther, Bocconi University

The rise of right-wing populists continues across the West, leaving many wondering how mainstream parties can respond. Part of the picture is the failure of political parties to meet voters’ views on immigration with policy responses.

Germany is a strong example here. In 2013, it had no notable right-wing populist party. Alternative for Germany (the AfD) already existed, but it was neither populist nor strongly anti-immigrant. But immigration into Germany was increasing.

In the years before 2013, several hundred thousand asylum seekers from Africa and the Middle East entered the country each year. Many Germans wanted lower immigration, but German political parties did not offer corresponding policies. The public and parliamentarians were already on a different page.

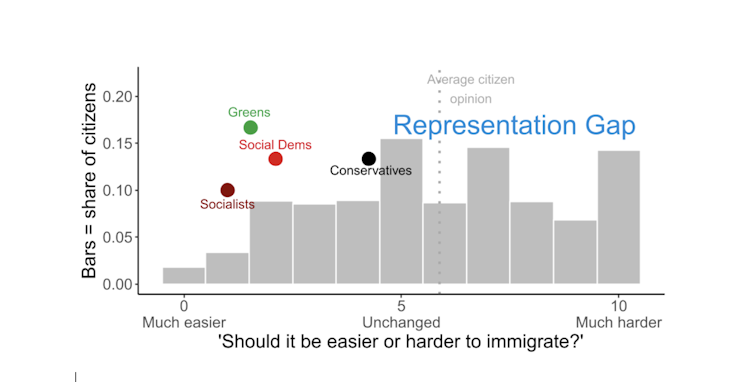

To measure this disagreement, researchers asked representative samples of German parliamentarians and ordinary citizens the following question in 2013: “Should it be easier or harder for foreigners to immigrate?”

They could choose from 11 responses, ranging from “0 – immigration for foreigners should be much easier” to “10 – immigration for foreigners should be much harder”.

The results show that most Germans wanted to restrict immigration in 2013. Despite this public demand, nearly all parliamentarians from all four major parties wanted to facilitate immigration.

Immigration attitudes in 2013:

L Guenther, CC BY-ND

Two years later, in 2015, the refugee crisis began. Over just a few years, two million asylum seekers entered Germany. In response, Germans viewed immigration as an increasingly important issue and increasingly voted based on their attitudes towards immigration. Because most Germans wanted lower immigration, the demand for an anti-immigration party increased.

During this time, the AfD changed its policy platform to become Germany’s only party, calling for much lower immigration. As a result, the AfD became the only party to represent the will of many Germans on the issue they considered most important.

Immigration attitudes in 2017:

From this perspective, it is not surprising that the AfD strongly increased its vote share in the 2017 election and became the first party to the right of the conservatives ever to enter the federal parliament.

In my research, I found similar patterns across Europe. In 27 countries, most political mainstream parties are much more in favor of immigration than the majority of their voters and citizens demand.

The representation gap is systematic across countries, political issues, and voter subgroups. On nearly all cultural issues, such as multiculturalism or gender relations, I found that voters are more conservative than their parliamentarians.

Across Europe, the difference between the average voter and parliamentarian is as large as the difference between the average conservative and socialist parliamentarian.

Even voters with the same level of education, or voters who are well-informed about politics, are much more culturally conservative than their representatives. Even immigrants themselves are much more opposed to immigration and multiculturalism than the average parliamentarian.

While these cultural representation gaps have existed for a long time, the increase in their salience and perceived importance contributes to the rise of rightwing populism. The increased importance of immigration most strongly drives this.

These results matter because they can equip politicians with the information they need to win (back) voters. On a deeper level, these findings raise the question of whether mainstream parties need to adjust their policies on immigration.

One crucial argument of mainstream politicians against populists is that once populists come to power, they aim to establish dictatorships and then rule against the interests of the people. However, this argument rings hollow if mainstream parties are unwilling to acknowledge and act on the issues considered most important by the people.![]()

Laurenz Guenther, Postdoctoral researcher, Department of Economics, Bocconi University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.