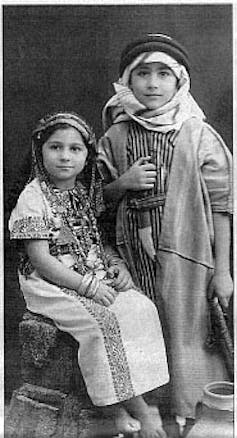

Edward Said tells the story of how Britain took away his mother’s Palestinian identity in 1932 by tearing up her passport to give her *place and her card to a Jewish immigrant to Palestine’ pic.twitter.com/dqwy3LAdRd

— Maria (@real1maria) December 29, 2023

Wikimedia

Cyma Hibri, University of Sydney

Whether you’re conscious of it or not, you likely have a vivid mental image of what the Middle East looks and sounds like. You might envision a sparse landscape, the air warped by heat and yellowed with flurries of sand. You might hear the plucking of an oud, or a haunting voice singing in a double harmonic scale.

This viral TikTok video captures just how salient these tropes are in our collective awareness and in popular media. Here, TikTokers collaboratively satirize features commonly found in Hollywood films about the Middle East, such as Beirut (2018), American Sniper (2014), and Argo (2012).

The video spoofs “the yellow filter,” a color-grading style used when depicting places perceived as impoverished or rife with conflict. We also hear a crude rendition of “Arabic” music, and someone poses as a “lady in lots of fabric staring at the camera,” parodying the unsettling mystique attributed to Middle Eastern women.

These tropes form a part of what Palestinian-American intellectual and activist Edward Said called Orientalism. His seminal 1978 book of the same name explores the ways Western experts, or “Orientalists”, have come to understand and represent the Middle East.

Said analyses a vast, organized body of knowledge on the Middle East, starting with Napoléon’s 1798 invasion of Egypt, for which a legion of scholars, writers, and scientists were enlisted to collect as much information about Egypt as they could. Orientalism peels back the supposedly neutral veneer of scientific interest and discovery attached to such projects.

Said shows how Orientalist writings and ideologies actively shape the world they describe and how they perpetuate views of Middle Eastern people as inferior, subservient, and in need of saving. As a result, these often racist or romanticized stereotypes create a worldview that justifies Western colonialism and imperialism.

What is “the Orient”?

According to Said, the Orient is a “semi-mythical construct” imposed on a set of countries east of Europe. While the term has been used to describe countries in East and South Asia, Said mainly focuses on how it’s used in relation to Southwest Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Indeed, the Orient doesn’t have a stable set of geographical bounds. Orientalists might write about countries as varied as Lebanon, Turkey, and Iraq with little distinction. Consequently, the geographical vagueness of “the Orient” works to conflate a vast and diverse array of landscapes, peoples, and cultures into a single, unchanging unit.

Orientalists often describe parts of Southwest Asia and North Africa with the intention of representing the entire Orient, and a wide range of moral attitudes, religions, languages, cultures, and political structures are folded into one.

As such, the idea of the Orient functions more as an abstract antithesis of the West defines itself against than as an accurate descriptor of a region.

Who are “the Orientals”?

The term “Oriental” was often used to describe any person or group of people east of Europe, usually from Arab and/or Islamic countries. Like “the Orient,” this term reduces a variety of peoples to a discrete set of traits and temperaments.

In his book, Said observes a spate of harmful and sometimes contradictory stereotypes of so-called Oriental peoples, who are described as lazy, suspicious, gullible, mysterious, or untruthful.

Said argues that by minimizing the rich diversity of Southwest Asian and North African peoples, Orientalists turn them into a “contrasting image” against which the West seems culturally superior.

The people of the Middle East are often portrayed as weak, barbaric, and irrational. Westerners, in comparison, are made to seem strong, progressive, and rational. This style of thinking, in which East and West, or Orient and Occident, are placed into a mutually exclusive binary, is central to Orientalist thought.

What is an “Orientalist”?

Said mounts much of his study of Orientalism on analyses of academic research. In his book, Said mainly focuses on academics working in philology and anthropology: those who wrote about the languages and cultures of Southwest Asia and North Africa.

He shows how these researchers fashioned their highly selective, biased observations into supposedly “scientific” findings, thus positioning themselves as objective authorities on Southwest Asia and North Africa.

But Orientalists aren’t exclusively tucked away in ivory towers. Said also explores the work of authors, poets, painters, philosophers, and politicians, citing figures as varied as Arthur Balfour, Victor Hugo, and Eugène Delacroix.

More than “a mere collection of lies”

It’s important to note that, for Said, Orientalism isn’t just a set of myths. He understood it as an interconnected system of institutions, policies, narratives, and ideas.

Said referred to this as the interaction between “latent Orientalism” (the system of implicit ideas and beliefs about Southwest Asia and North Africa) and “manifest Orientalism” (explicit policies and ideologies acted upon by institutions).

What keeps Orientalism flourishing and relevant is its consistent and active traffic between a variety of fields. Findings in academia inform foreign and domestic policies. Portrayals in popular culture influence the framing of news about Southwest Asia and North Africa, and vice versa. Seeing the links between culture, knowledge, and power is fundamental to understanding the reach of Orientalism.

What does Orientalism do?

Orientalism served as an ideological basis for French and British colonial rule. However, Orientalist perceptions didn’t simply disappear after the colonial period. In fact, they continue to be used as justification for contemporary foreign and domestic policies.

And this, Said stresses, is how Orientalism sustains its power: through repetition. Orientalist ideas, stereotypes, and approaches have been renewed and reiterated over the past two centuries, and we can still see them in circulation today.

For instance, we can see them at work in the ways the United States and European Union have endowed themselves with the authority to impose what a 2022 UN report called “suffocating” economic sanctions against Syria.

While the US Department of State has justified the unilateral sanctions as a means to “deprive [Bashar al-Assad’s] regime of the resources it needs to continue violence against civilians,” the sanctions have disproportionately affected the civilian population in Syria.

What’s more, these justifications contain the central assumption Said critiques in his book: that Southwest Asian and North African peoples need to be saved from themselves. The price of this so-called salvation is the agency and self-determination of these populations.

A note on context

Many scholars note that Said’s lived experience offered him a unique perspective in writing “Orientalism.” Said himself acknowledged this. In his 2003 preface, he wrote, “Much of the personal investment in this study derives from my awareness of being an ‘Oriental’ as a child growing up in two British colonies.”

His family was exiled from Mandate Palestine during the 1948 Nakba, and he went on to live in Lebanon, Egypt, and the United States. Educated in British colonial schools and elite US universities, Said linked the experience of being at once an insider and an outsider to the disparity he felt between his own identity as a Palestinian Arab and how Arabs are represented by the West.

Why is Orientalism important?

The impact of “Orientalism” is monumental. Said is often credited with founding the field known as postcolonial studies, and his work has significantly influenced fields across the humanities, including cultural studies, anthropology, comparative literature, and political science.

We can also attribute the growing awareness of Orientalist tropes to his book’s vast popularity. “Orientalism” has been translated into 36 languages (as of 2003) and remains a classic available in most bookstores.

While media literacy about Orientalism is increasing, these tropes remain as relevant as ever in the Western popular imagination. We should continue to challenge the ways Orientalism shapes our perception of Southwest Asia and North African countries and peoples.![]()

Cyma Hibri, PhD, University of Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

B

B

85 Comments

Pingback: stress relief

Pingback: cialis soft online

Pingback: zoloft euphoria

Pingback: escitalopram generic for lexapro

Pingback: gabapentin wholesale

Pingback: does lexapro help with anxiety

Pingback: what drugs should not be taken with cymbalta

Pingback: a streptokokken azithromycin

Pingback: precio de keflex 250 mg

Pingback: drink alcohol while taking cephalexin

Pingback: ciprofloxacin with alcohol

Pingback: bactrim 800 mg

Pingback: blood pressure medicine cozaar

Pingback: effexor weight gain

Pingback: ddavp and fluid restriction

Pingback: simvastatin ezetimibe aortic stenosis

Pingback: losing weight on contrave

Pingback: diclofenac sodium 75

Pingback: can flomax raise blood pressure

Pingback: how does aripiprazole work

Pingback: side effect of baclofen 10 mg

Pingback: another name for celebrex

Pingback: celecoxib 200mg capsules

Pingback: augmentin 875 price

Pingback: bupropion seizure

Pingback: remeron and cymbalta

Pingback: diffundox xl tamsulosin side effects

Pingback: is robaxin addictive

Pingback: can you take ibuprofen with tizanidine

Pingback: repaglinide torrinomedica

Pingback: what are the side effects of protonix

Pingback: is abilify a mood stabilizer

Pingback: acarbose pdf

Pingback: rx pharmacy generic viagra

Pingback: sildenafil warnings

Pingback: sildenafil for dogs

Pingback: generic name for ivermectin

Pingback: ivermectin 5

Pingback: stromectol pill for humans

Pingback: tadalafil buy

Pingback: stromectol tablets uk

Pingback: viagra tablet cost in india

Pingback: viagra over the counter australia

Pingback: stromectol 0.1

Pingback: gabapentin for anxiety dose

Pingback: lisinopril dosing

Pingback: keflex dosage for dogs

Pingback: modafinil kosten indien

Pingback: how long does valtrex take to work to prevent transmission

Pingback: tadalafil hims

Pingback: online pharmacy without prescriptions

Pingback: vardenafil patent expiration

Pingback: sildenafil for sale

Pingback: alcohol and sildenafil

Pingback: tadalafil to sildenafil conversion

Pingback: female cialis 10mg

Pingback: how long does it take sildenafil to work

Pingback: can i get misoprostol at a pharmacy

Pingback: online pharmacy that fills oxycodone

Pingback: sildenafil 20 mg tablet

Pingback: how long does 20mg sildenafil last

Pingback: does cialis help with premature ejaculation

Pingback: how many mg of tadalafil should i take

Pingback: what is tadalafil generic for

Pingback: online pharmacy generic propecia

Pingback: tadalafil dosage for erectile dysfunction

Pingback: xanax pills online pharmacy

Pingback: is ibuprofen the same thing as aspirin

Pingback: carbamazepine for mood swings

Pingback: compare etodolac meloxicam

Pingback: consecuencias del celecoxib

Pingback: tegretol gebelikte kullan脹m脹

Pingback: can i purchase generic pyridostigmine without insurance

Pingback: mebeverine suspension

Pingback: prophylactic indomethacin for preterm infants a systematic review and meta-analysis

Pingback: mestinon reviews

Pingback: elavil and overdose

Pingback: lioresal intrathecal baclofen injection

Pingback: does maxalt thin your blood

Pingback: piroxicam green

Pingback: can i get toradol without a prescription

Pingback: artane castle bookshop

Pingback: interaction between tizanidine and cipro

Pingback: can you get generic ketorolac tablets

Pingback: Homepage