The Act was adopted in the aftermath of the coup attempt in the Soviet Union on 19 August, when hardline Communist leaders attempted to restore central Communist party control over the USSR. In response (during a tense 11-hour extraordinary session), the Supreme Soviet (parliament) of the Ukrainian SSR, in a special Saturday session, overwhelmingly approved the Act of Declaration. The Act passed with 321 votes in favor, 2 votes against, and 6 abstentions (out of 360 attendants).

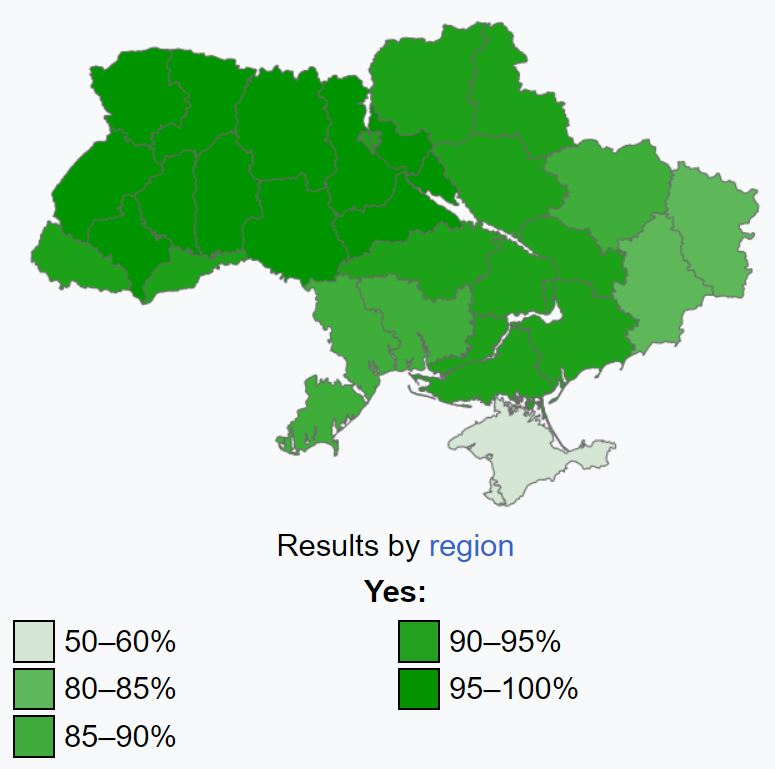

In the independence referendum on 1 December 1991, the people of Ukraine expressed deep and widespread support for the Act of Declaration of Independence, with more than 90% voting in favor and 84% of the electorate participating.

Ukrainian media had converted en masse to the independence ideal.

Polls showed 63% support for the “Yes” campaign in September 1991; that grew to 77% in the first week of October 1991 and 88% by mid-November 1991. 55% of the ethnic Russians in Ukraine voted for independence. The Act of Independence was supported by a majority of participating voters in each of the 27 administrative regions of Ukraine: 24 oblasts, 1 autonomous republic, and 2 special municipalities (Kyiv City and Sevastopol City). Voter turnout was lowest in Eastern and Southern Ukraine.

The six regions with the lowest percentage of “yes” votes were Kharkiv, Luhansk, Donetsk, and Odesa Oblasts, Crimea, and Sevastopol; all of those regions still had a majority of registered voters marking their ballots “yes,” except for Crimea and Sevastopol.

The referendum occurred on the same day as Ukraine’s first direct presidential election; all six candidates supported independence and campaigned for a “yes” vote. The referendum’s passage ended any realistic chance of the Soviet Union remaining together, even on a limited scale; Ukraine had long been second only to Russia in economic and political power in the USSR.

A week after the election, newly elected president Leonid Kravchuk joined his Russian and Belarusian counterparts (Boris Yeltsin and Stanislav Shushkevich, respectively) in signing the Belovezh Accords, which declared that the Soviet Union had ceased to exist.[9] The Soviet Union officially dissolved on 26 December.[10]

Poland and Canada were the first countries to recognize Ukraine’s independence on 2 December 1991. On the same day (2 December), it was reported during the late-evening airing of the television news program Vesti that the President of the Russian SFSR, Boris Yeltsin, had recognized Ukraine’s independence.[15]

The United States did so on 25 December 1991. That month the independence of Ukraine was recognized by 68 states, and in 1992, it was recognized by another 64 states.

The former Soviet Union had its nuclear program expanded to only four of its republics: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Russia, and Ukraine. After its dissolution in 1991, Ukraine became the third largest nuclear power in the world and held about one-third of the former Soviet nuclear weapons, delivery system, and significant means of its design, knowledge, and production. Ukraine inherited about 130 UR-100N intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) with six warheads each, 46 RT-23 Molodets ICBMs with ten warheads apiece, as well as 33 heavy bombers, totaling approximately 1,700 nuclear warheads, remained on Ukrainian territory.

Formally, these weapons were controlled by the Commonwealth of Independent States, specifically by Russia, which had the launch sequence and operational control of the nuclear warheads and its weapons system. In 1994, Ukraine, citing its inability to circumvent Russian launch codes, reached an understanding to transfer and destroy these weapons and become a party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

Until Ukraine gave up the Soviet nuclear weapons stationed on its soil, it had the world’s third-largest nuclear weapons stockpile, of which Ukraine had physical but no operational control. Russia controlled the codes needed to operate the nuclear weapons through electronic Permissive Action Links and the Russian command and control system, although this could not be a sufficient guarantee against Ukrainian access. Formally, these weapons were controlled by the Commonwealth of Independent States. Belarus only had mobile missile launchers, and Kazakhstan had chosen to give up its nuclear warheads and missiles to Russia quickly. Ukraine went through a period of internal debate on its approach.

The Lisbon Protocol to the START I Treaty

On 23 May 1992, Russia, the U.S., Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine signed the Lisbon Protocol to the START I treaty, ahead of ratifying the treaty later. The protocol committed Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine to adhere to the NPT as non-nuclear weapons states as soon as possible. However, the terms for the transfer of the nuclear warheads were not agreed upon, and some Ukrainian officials and parliamentarians started to discuss the possibility of retaining some of the modern Ukrainian-built RT-23 (SS-24) missiles and Soviet-built warheads.

In 1993, two regiments of UR-100N (SS-19) missiles in Ukraine were withdrawn to storage because warhead components were past their operational life, and Ukraine’s political leadership realized that Ukraine could not become a credible nuclear military force as they could not maintain the warheads and ensure long term nuclear safety. Later in 1993, the Ukrainian and Russian governments signed a series of bilateral agreements giving up Ukrainian claims to the nuclear weapons and the Black Sea Fleet in return for $2.5 billion of gas and oil debt cancellation and future supplies of fuel for its nuclear power reactors. Ukraine agreed to ratify the START I and NPT treaties promptly. This caused severe public criticism leading to the resignation of Ukrainian Defence Minister Morozov.[4] On 18 November 1993, the Rada passed a motion agreeing to START I but renouncing the Lisbon Protocol, suggesting Ukraine would only decommission 36% of missile launchers and 42% of the warheads on its territory, and demanded financial compensation for the tactical nuclear weapons removed in 1992. This caused U.S. diplomatic consternation, and the following day Ukrainian President Kravchuk said, “We must get rid of [these nuclear weapons]. This is my viewpoint from which I have not and will not deviate.” He then brought a new proposal to the Rada.

On 15 December 1993, U.S. Vice President Al Gore visited Moscow for a meeting. Following side discussions, a U.S. and Russian delegation, including U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense William J. Perry, flew to Ukraine to agree to the outlines of a trilateral agreement, including U.S. assistance in dismantling the nuclear systems in Ukraine and compensation for the uranium in nuclear warheads. Participants were invited to Washington on 3–4 January to finalize the agreement. A Trilateral Statement with a detailed annex was agreed, based on the previously agreed terms but with detailed financial arrangements and a firm commitment to an early start to the transfer of at least 200 warheads to Russia and the production in Russia of nuclear reactor fuel for Ukraine. Warheads would be removed from all RT-23s (SS-24) within ten months. However, Ukraine did not want a commitment to transfer all warheads by 1 June 1996 to be made public for domestic political reasons, and Russia did not want the financial compensation for uranium made public because they were concerned that Belarus and Kazakhstan would also demand this. It was decided to exclude these two matters from the published agreement but cover them in private letters between the countries’ presidents.

Another key point was that U.S. State Department lawyers made a distinction between “security guarantee” and “security assurance,” referring to the security guarantees that Ukraine desired in exchange for non-proliferation. “Security guarantee” would have implied the use of military force in assisting its non-nuclear parties attacked by an aggressor (such as Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty for NATO members), while “security assurance” would specify the non-violation of these parties’ territorial integrity. In the end, a statement was read into the negotiation record that the (according to the U.S. lawyers) lesser sense of the English word “assurance” would be the sole implied translation for all appearances of both terms in all three language versions of the statement.

President Clinton made a courtesy stop at Kyiv on his way to Moscow for the Trilateral Statement signing, only to discover Ukraine was having second thoughts about signing. Clinton told Kravchuk not signing would risk major damage to U.S.-Ukraine relations. After some minor rewording, the three presidents in Moscow signed the Trilateral Statement in front of the media on 14 January 1994.

The Budapest Memorandum

The Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances comprises three substantially identical political agreements signed at the OSCE conference in Budapest, Hungary, on 5 December 1994, to provide security assurances by its signatories relating to the accession of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). The three memoranda were originally signed by three nuclear powers: the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States. China and France gave somewhat weaker individual assurances in separate documents.

The memoranda, signed in Patria Hall at the Budapest Convention Center with US Ambassador Donald M. Blinken, amongst others in attendance, prohibited the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States from threatening or using military force or economic coercion against Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan, “except in self-defense or otherwise in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.” As a result of other agreements and the memorandum, between 1993 and 1996, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine gave up their nuclear weapons.

According to the three memoranda, Russia, the US, and the UK confirmed their recognition of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine becoming parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and effectively abandoning their nuclear arsenal to Russia and that they agreed to the following:

- Respect the signatory’s independence and sovereignty in the existing borders.

- Refrain from the threat or the use of force against the signatory.

- Refrain from economic coercion designed to subordinate to their own interest the exercise by the signatory of the rights inherent in its sovereignty and thus to secure advantages of any kind.

- Seek immediate Security Council action to provide assistance to the signatory if they “should become a victim of an act of aggression or an object of a threat of aggression in which nuclear weapons are used.”

- Refrain from the use of nuclear arms against the signatory.

- Consult with one another if questions arise regarding those commitments.

Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

In February and March 2014, Russia invaded and subsequently annexed the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine. This event took place in the relative power vacuum in the immediate aftermath of the Revolution of Dignity and was the beginning act of the wider Russo-Ukrainian War.

The events in Kyiv that ousted Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych on 22 February 2014 sparked pro-Russian demonstrations as of 23 February against the incoming new Ukrainian government. At the same time, Russian President Vladimir Putin discussed Ukrainian events with security service chiefs remarking that “we must start working on returning Crimea to Russia.” On 27 February, Russian troops captured strategic sites across Crimea, followed by the installation of the pro-Russian Aksyonov government in Crimea, the Crimean status referendum, and the declaration of Crimea’s independence on 16 March 2014. Although Russia initially claimed its military was not involved in the events,[38] Putin later admitted that troops were deployed to “stand behind Crimea’s self-defense forces.” Russia formally incorporated Crimea on 18 March 2014.

Following the annexation, Russia escalated its military presence on the peninsula and made threats to solidify the new status quo on the ground.

Ukraine and many other countries condemned the annexation and consider it to be a violation of international law and Russian agreements safeguarding the territorial integrity of Ukraine. The annexation led to the other members of the then-G8 suspending Russia from the group and introducing sanctions. The United Nations General Assembly also rejected the referendum and annexation, adopting a resolution affirming the “territorial integrity of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders” and referring to the Russian action as a “temporary occupation.”

The Russian government opposes the “annexation” label, with Putin defending the referendum as complying with the principle of the self-determination of people.

Ukraine was beautifull, but now it will become great!

— Olena Tregub (@OTregub) August 24, 2022

In pictures pic.twitter.com/3QLgNgCzbE

— Ian (@Ian___F) August 25, 2022

According to Ihor Lutsenko, the Russians are burning Ukraine’s wheat crop on purpose. Since the stalks are now dry, the whole field is on fire in a matter of minutes. pic.twitter.com/pXdpIcY0Gq

— UkraineWorld (@ukraine_world) July 7, 2022

This was the moment of truth.

Russia launched its invasion of 🇺🇦 exactly 6 months ago. Russian media quickly spread rumors that Zelensky had fled the country.

Instead he asked for ammo & aired a famous video of him saying “your president is here, we’re all here”.

No surrender! pic.twitter.com/XfgZtKjCKe

— Visegrád 24 (@visegrad24) August 24, 2022

7 Comments

Pingback: Russian losses in Ukraina "special military operation" - Bergensia

Pingback: read here

Pingback: click here to investigate

Pingback: passive income investments

Pingback: ephedra sinica tea for sale

Pingback: magic mushrooms for sale online australia

Pingback: jazz cafe