Ee Ling Ng, University of Melbourne and Deli Chen, University of Melbourne

The next time you bite into an apple, spare a thought for the soils that helped to produce it. Soils play a vital role, not just in an apple’s growth, but in our own health too.

The formation of soil, pedogenesis, is a very slow process. Creating one millimetre of soil coverage can take anything from a few years to an entire millennium.

But with soils around the world under threat, we’re in danger of losing their health benefits faster than they are replaced.

Healthy soils for healthy plants

A healthy soil is a living ecosystem in which dead organic matter forms the base of a food web consisting of microscopic and larger organisms.

Together, these organisms sustain other biological activities, including plant, animal and human health. Soils supply nutrients and water, which are vital for plants, and are home to organisms that interact with plants, for better or worse.

In the natural environment, plants form relationships with soil microbes to obtain water, nutrients and protection against some pathogens. In return, the plants provide food.

The use of mineral fertilisers can make some of these relationships redundant, and their breakdown can lead to the loss of other benefits such as micronutrients and disease protection.

Certain farming practices, such as tillage (or mechanical digging), are harmful to fungi in soils. These fungi play important roles in helping plants obtain crucial nutrients such as zinc.

Zinc is an essential micronutrient for all living organisms. Zinc deficiency affects an estimated one-third of the world’s population, particularly in regions with zinc-deficient soils. If food staples such as cereal grains are grown on zinc-deficient soils and further lack their fungi helpers, they become deficient in zinc.

If the way food is grown affects the composition and health of plants, could farming practices that focus on soil health make food more nutritious? A recent review on fruits says yes.

The researchers found that fruits produced under organic farming generally contained more vitamins, more flavour compounds such as phenolics, and more antioxidants when compared with conventional farming. Many factors are at play here, but pest and soil management strategies that benefit soil organisms and their relationship with plants are part of the equation.

The composition and function of animals and humans reflects, to some extent, what they eat. For example, the fish you eat is only rich in omega-3 fatty acids if the fish has eaten algae and microbes that manufacture these oils. The fish itself does not produce these compounds.

Increasing numbers of studies are demonstrating the link between nutrition and human health issues. We know, for example, that antioxidants, carbohydrates, saturated fat content and the ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids contribute to immune system regulation.

We do not produce some of these nutrients; we must obtain them through our food. Therefore, how food is grown is a matter of public health.

Beyond nutrition

Soil is the greatest reservoir of biodiversity. A handful of soil can contain millions of individuals from thousands of species of bacteria and fungi, not to mention the isopods, rotifers, nematodes, worms and many other identified and yet-to-be-identified organisms that call soil home.

Soil microbes produce an arsenal of compounds in their chemical warfare for dominance and survival. Many widely used antibiotics and other drugs were isolated from soil. It may hold the answers to our battle with antibiotic resistance and other diseases including cancer.

It has also been suggested that exposure to diverse microbes in the natural environment can help prevent allergies and other immune-related disorders.

The road to healthy soils

Unfortunately, we are doing a poor job of looking after our soils. About two-thirds of agricultural land in Australia is suffering from acidification, contamination, depletion of nutrients and organic matter, and/or salinisation. And in case anyone forgets, soil is every bit as non-renewable as oil because soil formation is such a slow process.

On the other hand, soil erosion can happen very quickly. For a taste of what happens when soils are destroyed, nothing beats sitting through a dust storm and watching day turn into night. Dust storms inspired George Miller’s film Mad Max: Fury Road.

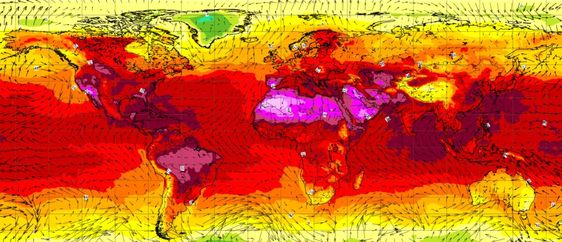

In the 2009 Red Dawn in Sydney, some 2.5 million tonnes of soil were lost within hours to the ocean in a 3,000km-long, 2.5km-high dust plume.

Australia’s major cities began on fertile land. Melbourne’s food bowl can supply 41% of the city’s fresh food needs. Such secure access to fresh and whole food needs our protection.

Healthy soils are part of the solution to some of our dilemmas – poverty, malnutrition and climate change – as they underpin processes that gives us food, energy and water. If we want to meet the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, soil health is a linchpin we cannot ignore.

![]() From this perspective, agricultural practices to maintain healthy soil are clearly an important target for policymakers. Looking after our soils ultimately means looking after ourselves.

From this perspective, agricultural practices to maintain healthy soil are clearly an important target for policymakers. Looking after our soils ultimately means looking after ourselves.

Ee Ling Ng, Research fellow, University of Melbourne and Deli Chen, Professor, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

4 Comments

Pingback: เจ้าภาพยูโร 2024 กับการแข่งขันสุดเดือด

Pingback: thai massage liestal

Pingback: snow bunnies

Pingback: ทรรศนะบอลวันนี้