Alana Malinde S.N. Lancaster, The University of the West Indies, Barbados

As the gavel came down on the latest round of climate talks in Dubai, there were declarations of “we united, we acted, we delivered” from the COP28 presidency. This was met by a sense of déjà vu among the Alliance of Small Island States (Aosis) delegates, an intergovernmental organization representing the nations most vulnerable to climate change.

In her post-summit statement, Aosis lead negotiator Anne Rasmussen expressed confusion that the UAE Consensus, COP28’s final agreement, was approved when representatives from small island developing states (or Sids were not in the room.

While some delegates hailed the consensus as the “beginning of the end” of the fossil fuel era, Aosis countered that the document contained a “litany of loopholes” that did little to advance the key actions needed to stave off climate breakdown and deliver justice to islands and low-lying states facing the gravest consequences of the climate crisis.

Aosis member states came to COP28 to build on the momentum of their victory in the final moments of COP27 a year earlier in Egypt, when delegates agreed to establish a loss and damage fund that would pay developing nations for the unavoidable and extreme consequences of climate change. The group had fought for over 30 years in climate negotiations for this fund.

Additionally, Aosis identified fundamental areas required to save Sids from impacts such as rising sea levels, desertification, and climate migration. The principal – and most contentious – is “a phase-out” of fossil fuels, the main driver of the climate crisis.

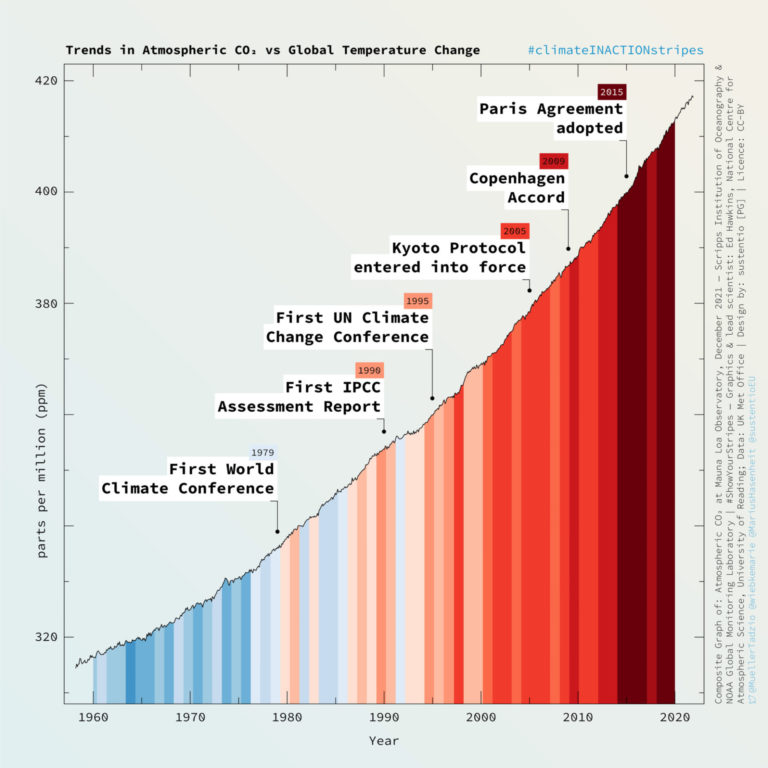

Scientific evidence is clear: rapidly eliminating coal, oil, and gas must limit global warming to 1.5°C, as enshrined in the Paris Agreement. Even at this limit, many small islands will face a drastic increase in coastal flooding from rising sea levels and other effects that could render these countries uninhabitable.

“We will not sign our death certificate. We cannot sign on to text that does not have strong commitments on phasing out fossil fuels,” said Cedric Schuster of Samoa, the Aosis chair at the negotiations.

In addition to keeping the 1.5°C goal alive, Aosis members emphasized the need to double the financing, which helps states pursue measures to adapt to climate change (such as building seawalls to protect from stronger storm surges) and to mitigate their emissions. Sids, including the Caribbean Community (Caricom), a political and economic union to which Aosis’ Caribbean Sids belong, had consistently raised these priorities ahead of COP28.

Shared problems

This unified approach is remarkable considering the diverse nature of the 39 low-lying Sids scattered across the Caribbean, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, and the South China Sea. This bond is also necessary, as SIDS comprise a mere 1% of the world’s population, and often, the influence of national delegations is diminished by financial and logistical constraints, such as access to visas. Such shared impediments arise because of the common history of colonialism and resource extraction, which has bequeathed unique challenges to small island states.

Despite this past and their relative tininess, Sids remain among the most biodiverse places on Earth. On average, the ocean under their control is 28 times each country’s land mass, and much of the natural wealth for SIDS lies in their ocean.

But the toll of climate change is mounting on these states. Pacific islands such as Vanuatu, Kiribati, and Tuvalu have seen atolls sinking. Caribbean islands such as Antigua and Barbuda, the Commonwealth of Dominica, and the Bahamas have experienced devastating hurricanes. In the case of Barbuda, the upheaval caused by more violent storms has precipitated an attempt to transfer land from the island community to the government and transnational companies, threatening to disrupt more than 400 years of farming and fishing traditions.

The costs of failure

The UAE Consensus text “calls on” countries to “transition away from fossil fuels” and towards renewable energy. Tellingly, this formulation met with the approval of fossil fuel producers.

Other agenda items important to Sids at COP28 were deferred another year, including how markets for trading carbon offset credits will be regulated. Even the hard-won victory of a loss and damage fund may prove hollow, as its lopsided set-up gives donor countries disproportionate influence through the World Bank’s interim role as host and stacks the odds against recipients.

Estimates suggest that the combined total of US$700 million (£556 million) pledged by wealthy, high-emitting nations to compensate the poorest and least culpable countries for climate impacts amounts to 0.2% of the annual cost of climate destruction.

And, despite the vastness of ocean space under the control of SIDS and the increasingly recognized role of the ocean in sequestering carbon, much of the funding for ecosystem solutions to climate change has been funneled into forests.

What lies ahead?

While there were encouraging moments at COP28, the outcome failed to provide a scientifically grounded and equitable blueprint for keeping the Paris Agreement’s goal alive. For Sids, the delivery of this mandate was a red line for the 2023 climate negotiations. However, SIDS has not put their eggs solely in the basket of the UN climate negotiations.

In 2015, Pacific islands proposed a fossil fuel non-proliferation treaty to manage a phase-out between nations. This year, Colombia, dependent on coal, oil, and gas for half its exports, endorsed the idea.

Elsewhere, Aosis members, including Antigua & Barbuda and Vanuatu, seek advice on states’ legal obligations to prevent and remedy harm due to the climate emergency under the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and the International Court of Justice. African Sids have published a draft report outlining similar questions.

In the run-up to COP29 in Azerbaijan, Aosis members will need to continue to explore other routes to compel wealthy nations to recognize the needs and circumstances of the world’s most vulnerable states.

Alana Malinde S.N. Lancaster, Lecturer in Law & Head of the Caribbean Environmental Law Unit, Faculty of Law and Co-I, One Ocean Hub, The University of the West Indies, Barbados

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.