Tom Pettinger, University of Warwick

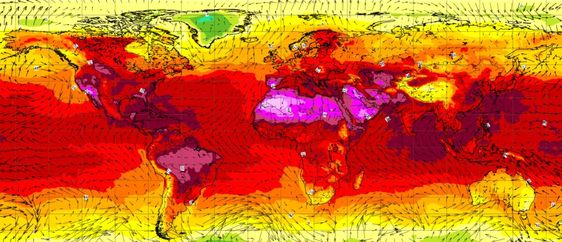

The dire state of the planet’s health was unambiguously demonstrated by the UN’s climate body, the IPCC, when it sounded a “code red” for humanity in its latest report.

Yet public involvement in environmental activism has consistently remained muted, particularly in the wealthier nations most responsible for the destruction of the environment.

In the UK, for example, peaceful protest by environmentalist groups like Extinction Rebellion tends to be opposed more than it’s supported. This is despite the limited disruption these groups cause in comparison to the extreme disruption already produced and threatened by climate breakdown, such as extreme droughts, wildfires, and tropical storms.

Recent protests blocking British motorways to call for the government to insulate homes have been met not with policy reform but with outrage and proposals to increase police power to arrest protesters.

Of course, such protests frustrate commuters and those visiting relatives in hospital – it would be surprising if they didn’t. But it’s curious that the annoyance of those commuters stokes far more media attention and outrage than the 150,000 yearly deaths occurring from the very thing being protested.

The dangers of consistent government inaction on climate are undeniably more dangerous than those posed by protest.

So why do so many people oppose the call for change in the face of a sixth mass extinction? Why is there resignation, rather than resistance?

Climate nonchalance

I believe that “affect theory” – a concept from political science that connects emotion and experience with political action – can help us make sense of the gap between our knowledge and what we do with that knowledge.

And I think that the lack of widespread mobilisation is borne, not from outright climate denial, but rather from a more insidious climate apathy: what might be called “climate nonchalance”.

This nonchalance – recognizing the impending collapse of our world and shrugging our shoulders – is made possible only by a profound separation between the comfortable lifestyles of the privileged and the consequences of those lifestyles elsewhere: including increased death rates, frequent exploitation, and environmental displacement for the less privileged.

Regions of the world emitting the most carbon, such as western Europe and the US, are projected to be least affected by shifts in global climate. The vast majority of UK citizens, for example, have not yet been displaced by drought, flooding, or other extreme weather events.

Yet this is a position not equally enjoyed across the world. The population of Bangladesh, for instance, is particularly vulnerable to climate change, with 30 million people set to become climate refugees if and when sea levels rise by one meter.

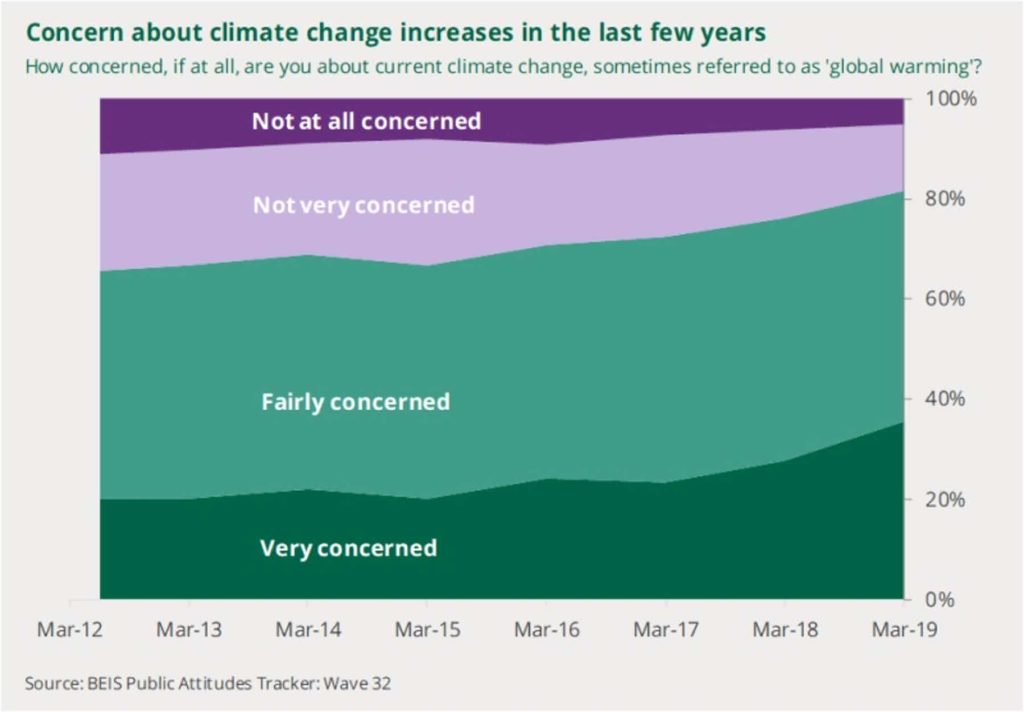

And while global concerns about climate change have grown over the last few years, this does not appear to be proportionately translated into action.

A 2019 IPSOS survey showed that in the UK, while a significant majority of respondents reported being concerned about the environment, only a third had changed their shopping habits as a result of climate concerns. And just 7% had either written to or tweeted a political representative about environmental issues. The same percentage, only 7%, had engaged in any climate campaigning at all.

Affect theory

Affect theory suggests that we are spurred into action when we personally experience the effects of something.

Surveys show those who consider themselves affected by climate change are more likely to show greater concern for the environment. Those who are more concerned, in turn, generally show more support for disruptive protests.

Experiencing an event like a severe flood produces a different response than merely hearing of one, even when we cognitively perceive that a disaster elsewhere may ultimately affect us.

However, people in countries like the UK are currently largely unaffected by the immediate, extreme consequences of ecological breakdown. This disconnect makes it significantly harder for them to perceive this threat’s scale and act proportionately.

But in light of warnings of ecological and societal breakdown, it’s imperative that our outrage is directed proportionately. We should support climate action that might not benefit us in the short term, and pressure politicians to tax aviation fuel, invest in renewable technologies, and rethink our culture of consumption.

We must move from nonchalance to action if we are to protect both our planet and those already living with the consequences of a collapsing world.![]()

Tom Pettinger, Research Fellow in Politics and International Studies, University of Warwick

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4 Comments

Pingback: rtp dultogel

Pingback: Empire777 มีความแตกต่างจากค่ายคาสิโนอื่นอย่างไร

Pingback: Lightning Speed Metrics

Pingback: เว็บปั้มติดตาม