Bill Laurance, James Cook University and Penny van Oosterzee, James Cook University

For time immemorial, many wildlife species have survived by undertaking heroic long-distance migrations. But many of these great migrations are collapsing right before our eyes.

Perhaps the biggest peril to migrations is so common that we often fail to notice them: fences. Australia has the longest fences on Earth. The 5,600-kilometre “Dingo Fence” separates southeastern Australia from the rest of the country, whereas the “Rabbit-Proof Fence” stretches for almost 3,300 kilometres across Western Australia.

Western Australia Department of Agriculture & Food

Both of these enormous fences were intended to repel rabbits and other “vermin” such emus, kangaroos and dingoes that were considered threats to crops or livestock. Built over a century ago, their environmental impacts were poorly understood or disregarded at the time.

Since construction these fences have caused recurring ecosystem catastrophes, such as mass die-offs of emus and other species trying to find food and water in a land notorious for the unpredictability of its rainfall, vegetation growth and fruit production.

Fatal fences

The same thing is happening across much of the planet. While a nemesis for larger wildlife, nobody knows how many fences exist today or where they’re located. A study that mapped all the fences in southern Alberta, Canada, found there were 16 times more fences than paved roads.

Scientists are waking up to the peril of fences, realising that from an environmental perspective they’re grossly understudied — “largely overlooked and essentially invisible,” according to a recent global review.

Duncan Kimuyu

In Africa, home to some of the most spectacular wildlife migrations, scientists found that of 14 large-mammal species known to migrate en masse, five migrations were already extinct. Proliferating fences, along with habitat loss and wildlife poaching, has sent ecosystems such as the Greater Mara in Kenya crashing into ecological turmoil.

And a 2009 audit of Earth’s greatest terrestrial-mammal movements showed that of 24 large species that once migrated in their hundreds to thousands, six migrations have vanished entirely.

Many remaining migrations are mere shards of their former glory. For instance, Indochina once had mass migrations of elephants and other large mammals, big cats, monkeys and birds — often called the “Serengeti of Southeast Asia”.

Pattarapong/iStock

The thundering herds of American bison – some numbering up to 4 million animals – which once dominated the plains of North America have all but vanished today.

How to save mass migration

There are two main ways to destroy mass migrations: killing the animals outright by hunting and over-harvesting, or stopping the animals from accessing food or water, typically by fencing them out or clearing and fragmenting their habitat.

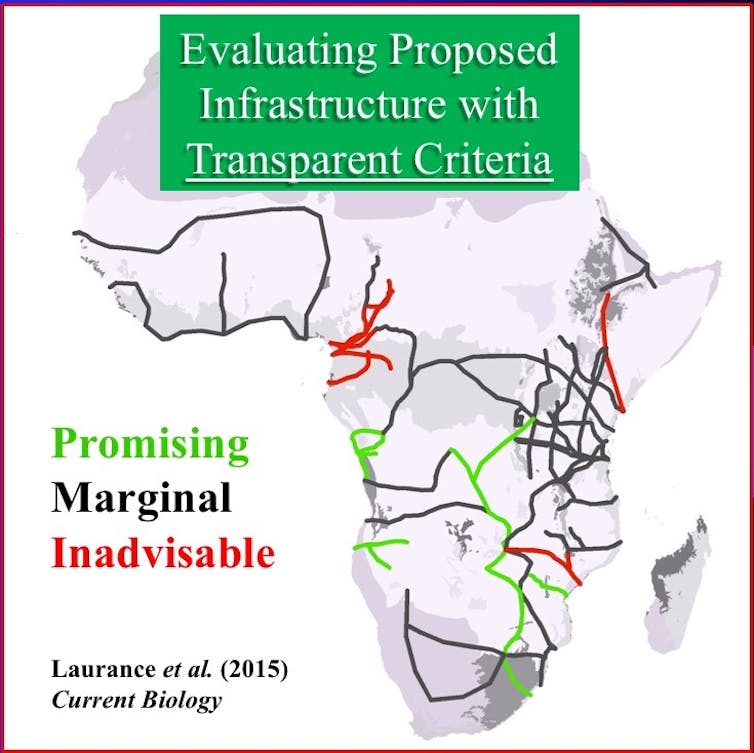

As the human footprint rapidly expands, scary things for wildlife are happening all over. Research that one of us (Bill Laurance) led revealed that 33 African “development corridors” would, if completed, exceed 50,000 kilometres in length and crisscross the continent, chopping its ecosystems into scores of smaller pieces.

William Laurance

Beyond this, over 2,000 parks and protected areas in Africa would be degraded or cut apart by the massive developments.

Migrations are vulnerable even in the seas. Recent research shows that growing shipping traffic is an increasing danger to migratory great whales, basking sharks, and giant whale-sharks – all highly vulnerable to collisions with fast-moving ships, as well as disruption of their sensitive hearing and vocal communications by shipping noise and sonar, and pollutants from vessels.

But the inspiring news is that, if you remove barriers such as fences, animal migrations can spontaneously resume – like a phoenix rising from the ashes.

Fernando Quevedo de Oliveira/Alamy Stock Photo

In 2004, a fence that had blocked a former zebra migration in Botswana was removed. By 2007 it was one of the longest animal-migration routes in the world.

And a few places on Earth are still free from fencing and fragmentation. The world-famous Seregeti ecosystem of Tanzania is an iconic example. In war-torn South Sudan, a spectacular mass migration of a million antelope — known as white-eared kob — is still intact because there are no fences.

And caribou still migrate in great herds across large expanses of northern Canada and Alaska.

Alarming news for Botswana

Collapsing migrations are a global concern, but right now conservationists are most worried about Botswana.

This mega-diverse nation in southern Africa is considering profoundly changing its wildlife management by expanding fences and cutting off wildlife migrations not considered beneficial to the country’s current priorities.

This would be a shocking decision, because Botswana’s wildlife conservation is almost entirely dependent on its mass migrations.

For wildebeest, zebra, eland, impala, kob, hartebeest, springbok and many other large migrants, isolation is a killer – destroying their capacity to track the shifting patterns of greening vegetation and water availability they need to survive.

And it’s not just grazing and browsing animals that are affected: entire suites of large and small predators, scavengers, commensal and migratory bird species, grazing-adapted plants and other species are integrally tied to these great migrations.

Michael Cohen

Botswana is already sliced into 17 giant “islands” by fences, erected in colonial times to protect the livestock of European farmers from foot-and-mouth disease.

But foot-and-mouth disease is far more likely to be spread by cattle, not wildlife. Fence-free strategies for managing disease risk also have have great potential.

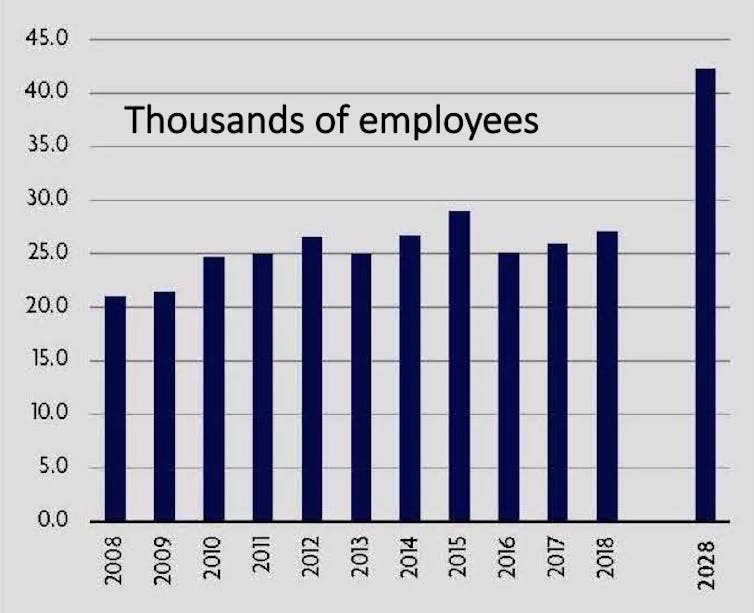

And nature tourism in Botswana is a large, vibrant, and growing part of the national economy. Ecotourists will continue to favour the nation so long as it maintains untrammelled areas and spectacular animal migrations.

Travel & Tourism Economic Impact: Botswana 2018

But you can kiss a lot of those tourism revenues goodbye if Botswana shatters its great migrations – killing off the spectacular living panoramas that are a magnet for the world’s nature lovers.

If we can avoid fencing and bulldozing critical parts of the Earth, we could hugely increase the chances that our most vibrant wildlife and ecosystems have a fighting chance to survive.![]()

Bill Laurance, Distinguished Research Professor and Australian Laureate, James Cook University and Penny van Oosterzee, Adjunct Associate Professor James Cook University and University Fellow Charles Darwin University, James Cook University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

15 Comments

Pingback: เกม 3D

Pingback: Angthong National Marine Park

Pingback: เสริมหน้าอก

Pingback: เช่ารถตู้พร้อมคนขับ

Pingback: arduino

Pingback: John Lobb

Pingback: the cali company disposable vapes

Pingback: เดิมพันอีสปอร์ต กับ PINNACLE เล่นง่าย

Pingback: free Stripchat

Pingback: 789bet

Pingback: profibus connector

Pingback: เฮงเฮง789

Pingback: กรอบแว่นสายตา

Pingback: ร้านแบตเตอรี่ใกล้ฉัน

Pingback: Giriş yapmak