Noël Brunetière, Université de Poitiers

With the rise in gas prices showing no signs of abating, it seems appropriate to ask ourselves: are our cars not efficient enough? Europe has decided to ban the production of new combustion engine-powered vehicles by 2035. However, most passenger vehicles currently on roads in France and across the globe still fall under this category.

Their engines burn petrol or diesel fuel and convert the resulting thermal energy into mechanical energy, which is used to propel the vehicle. At most, 50% of the power supplied is converted into mechanical energy, but the remainder is dissipated as heat. Moreover, not all the mechanical energy is delivered to the wheels, with almost 30% being lost due to friction.

In the end, the energy used to move the vehicle amounts to approximately 30% of the total energy supplied by fuel. So, where does all this waste occur, can we reduce it, and how much can we reasonably expect to save on fuel consumption?

How a combustion engine works

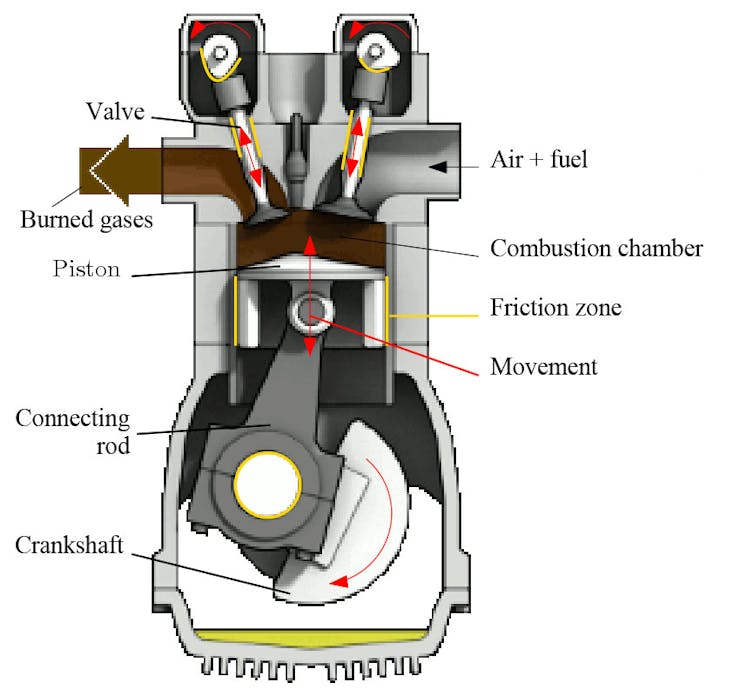

In a combustion engine, a mix of fuel and air is burned inside the part called the combustion chamber. This increases the volume of gas in the chamber, and the resulting pressure pushes the piston component downward. The piston is connected to the crankshaft by a connecting rod, which converts the piston’s vertical motion into a rotational motion. Next, the crankshaft transfers this rotation to the mechanical transmission (including the gearbox) and then to the wheels.

A number of engine valves open and shut, letting waste gases out and then a fresh dose of air and fuel in. A limited portion (40 to 50%) of the thermal energy resulting from combustion is converted into mechanical energy. The remainder is wasted, discharged through the hot gases from the exhaust pipe and the radiator, which keeps the engine cool. However, by improving the combustion and installing energy recovery systems, we may increase the amount of usefully converted energy and reduce fuel consumption by almost 30%.

Fuel wasted due to friction

It is worth mentioning what is meant by “friction.” The term refers to the force that resists the sliding motion between two objects when they are brought into contact. For example, the friction between our shoes and the ground allows us to walk without slipping. In cases of low friction, such as when the ground is icy, it is easier for our shoes to slide against the ground, and walking becomes much more difficult. We might, however, choose to wear skates, which use their low friction with the ground to enable us to move around by sliding.

When two objects are slid (or rubbed) together, the resultant resisting force occurs due to friction. This leads to energy loss through heat, which we can observe by rubbing our hands together, for instance. In a car, the same phenomenon occurs between the moving engine parts and the mechanical transmission. As researchers, we aim to assess the impact of this phenomenon.

“Tribology” is a branch of science concerned with contact, friction, and how to mitigate their impacts. Recent research in this field has helped estimate the energy losses due to the friction occurring in a car’s combustion engine and the transmission linked to its wheels. In the diagram above, the contact areas where losses occur due to friction are shown in yellow. The most significant energy losses occur around the piston (at approximately 45% of losses), followed by the links between the connecting rod, crankshaft, and cylinder block (approximately 30%), and around the valves and their actuating system (approximately 10%). The remaining 10% is lost through other engine fittings.

The useful mechanical energy from the engine is further restricted by losses in the mechanical transmission, particularly caused by friction between the gears. Ultimately, all these losses result in a wastage of around 30% of the mechanical energy the combustion engine supplies under average vehicle operating conditions.

Could we reduce fuel consumption by limiting energy losses from friction?

Because around 30% of a car’s fuel is used to overcome the friction between its moving mechanical parts, reducing these losses could yield substantial savings on fuel. As such, we must look at the elements exposed to friction to discuss potential improvements. The engine and transmission components are already lubricated using oil, and inserted between surfaces to prevent friction and wear.

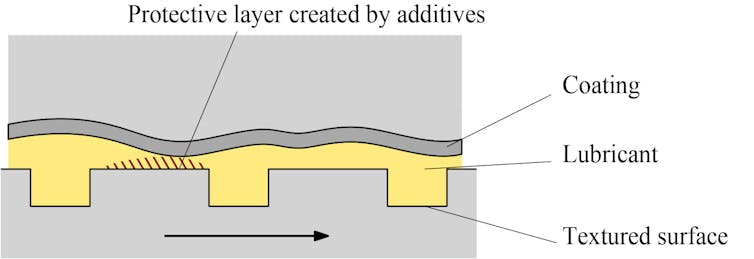

Tribology research covers two main areas to reduce energy losses from friction further. The first is concerned with improving lubricants. This research aims to manage how certain properties of lubricants, such as viscosity, are affected by temperature. In general, friction tends to decrease when a less viscous lubricant is used, but its oil film may be too thin, leading to more contact between uneven surface areas and faster wear. To combat this, one branch of research aims to develop new additives for lubricants that can coat surfaces in protective, low-friction layers.

The second research area involves improving the surfaces by creating new (particularly carbon-based) coatings, which protect the surfaces that come into contact with each other and result in lower friction. Alternatively, surfaces may be textured with a network of holes with the optimal dimensions for more effective lubrication.

We recently conducted a research project at the Institut Pprime in Poitiers (led by CNRS, University of Poitiers, and ISAE Ensma), which has shown that the friction of some contact types can be decreased by 50% through the use of surface texturing.

Furthermore, in the case of combustion engine-powered vehicles, several studies have already confirmed that this new technology can reduce energy losses due to friction by 50 to 60% in the medium term, amounting to around 15% less fuel consumption. When combined with improved engines and smaller, lighter vehicles – and, ultimately, narrower tires – this seemingly small amount of saved fuel could reach around 50%. However, the expanding SUV sector in the automotive market tells us that this avenue for fuel saving has sadly not been adopted by car manufacturers in recent years.

[Nearly 80,000 readers look to The Conversation France’s newsletter for expert insights into the world’s most pressing issues. Sign up now]

So, what are our immediate solutions for cutting costs? Excluding new vehicle purchases, using more efficient lubricants can reduce consumption by a few percent, a paltry amount, in the face of rising fuel prices. On top of this, it can be tricky for individuals to know which lubricant to choose from, as comparative studies are currently only available in the scientific literature and therefore restricted to a specialist readership.

Nevertheless, we should not forget that cars are made to transport several passengers. When fuel consumption is divided by several passengers, carpooling can cut consumption by two, three, or four times over and beyond. But when reducing fuel bills, driving less remains the most efficient and straightforward solution.

As for the longer term, could the electric car – now widely praised – be a more effective solution in reducing energy losses due to friction? With much fewer mechanical components exposed to friction, energy losses in electric cars have been evaluated at less than 5%. But before it can be hailed as a miracle solution, we must consider all the other nuts and bolts, including the car’s weight, battery cost, and the extraction and recycling of its manufacturing materials.![]()

Noël Brunetière, Directeur de recherche, Université de Poitiers

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

6 Comments

Pingback: fushion hair extension borehamwood

Pingback: Cannabis delivery Toronto

Pingback: buy LSD online

Pingback: บาคาร่า lsm99

Pingback: นำเข้าสินค้าจากจีน

Pingback: pakkumised ja teenused