They are a beastly people with a beastly religion. The famine was their own fault for breeding like rabbits. –Winston Churchill, inducing the Bengal famine of 1943

Ateqah Khaki, The Conversation, and Vinita Srivastava, The Conversation

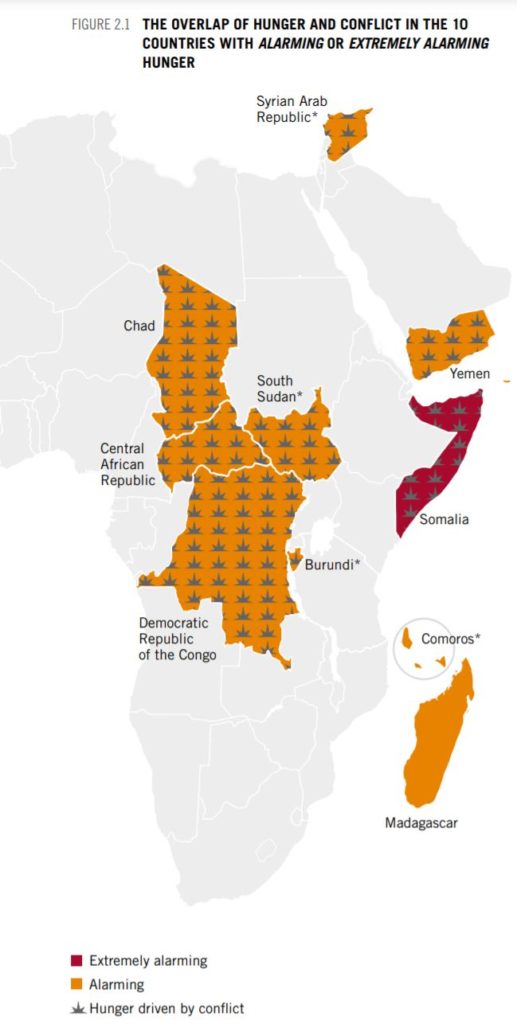

In this episode of Don’t Call Me Resilient, we continue our conversation about forced famine and its use as a powerful tool to control people, land, and resources. For centuries, starvation has been a part of the colonizer’s “playbook.”

We speak with two scholars to explore two historical examples: the decimation of Indigenous populations in the Plains, North America, which historian David Stannard has called the American Holocaust, and in India, the 1943 famine in Bengal. According to a recent BBC story, the Bengal famine of 1943 killed more than three million people. It was one of the worst losses of civilian life on the Allied side in the Second World War. (The United Kingdom lost 450,000 lives during that same war.)

Although disease, environmental disasters, and famine were features of life before colonialism, decades of research have shown how these occurrences were manipulated by colonial powers to prolong starvation and trigger chronic famine. In other words, starvation has been effectively used by colonial powers to control populations and acquire land and the wealth that comes with that. This colonization was accompanied by an “entitlement approach” and the belief that Indigenous populations were inferior to the lives of the colonizer.

According to scholars, prior to the arrival of colonialists, both populations at the heart of today’s episode were thriving with healthy and wealthy communities. Although disease and famine existed before the arrival of Europeans, it cannot be denied colonial powers accelerated and even capitalized on chronic famine and the loss of life due to disease and malnutrition.

As the famous economist Amartya Sen has said, famine is a function of repression. It springs from the politics of food distribution rather than a lack of food. Imperial policies such as the Boat Denial Policy and Rice Denial Policy meant that, as curator Natasha Ginwala wrote: “freshly harvested grain was set on fire, or even dumped into the river.”

(University of Regina Press)

Two experts on the North American and Bengal famines joined this episode.

James Daschuk is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology and Health Studies at the University of Regina. He is the author of Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation and the Loss of Aboriginal Life.

We also spoke with Janam Mukherjee, an Associate Professor of History at Toronto Metropolitan University and the author of Hungry Bengal: War, Famine and the End of Empire. Mukherjee was recently a primary historical advisor on the BBC Radio 4 series “Three Million,” a five-part documentary on the Bengal famine of 1943.

(Oxford University Press)

Listen and follow

You can listen to or follow Don’t Call Me Resilient on Apple Podcasts (transcripts available), Spotify, YouTube, or wherever you listen to your favorite podcasts.

You can read the transcript of this episode here.

We’d love to hear from you, including any ideas for future episodes.

Join the Conversation on Instagram, X, LinkedIn and use #DontCallMeResilient.

Resources

“When Canada used hunger to clear the West” (by James Daschuk, July 19, 2013)

Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation and the Loss of Indigenous Life (by James Daschuk, 2013)

“Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942–1952” (in Social History by Ian Mosby, 2013)

“Proposed class action seeks damages for intergenerational trauma from residential schools”

Ashes and Embers: Stories of the Delmas Indian Residential School by Floyd Favel

Churchill’s Secret War (by Madhusree Mukerjee, 2010)

Hungry Bengal: War, Famine and the End of Empire (by Janam Mukherjee, 2015)

“Three Million” (The documentary podcast by the BBC)

“Witnessing famine: the testimonial work of famine photographs and anti-colonial spectatorship” (Journal of Visual Culture by Tanushree Ghosh, 2019)

From the archives – in The Conversation

Ateqah Khaki, Associate Producer, Don’t Call Me Resilient, The Conversation and Vinita Srivastava, Host + Producer, Don’t Call Me Resilient, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

1 Comment

Pingback: Goal 2: Zero Hunger - Bergensia