Nick Golledge, Victoria University of Wellington

Climate Explained is a collaboration between The Conversation, Stuff and the New Zealand Science Media Centre to answer your questions about climate change. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, please send it to climate.change@stuff.co.nz

As an individual, what is the single, most important thing I can do in the face of climate change?

The most important individual climate action will depend on each person’s particular circumstances, but each of us can make some changes to reduce our own carbon footprint and to support others to do the same.

Generally, there are four lifestyle choices that can make a major difference: eat less or no meat, forego air travel, go electric or ditch your car, and have fewer children.

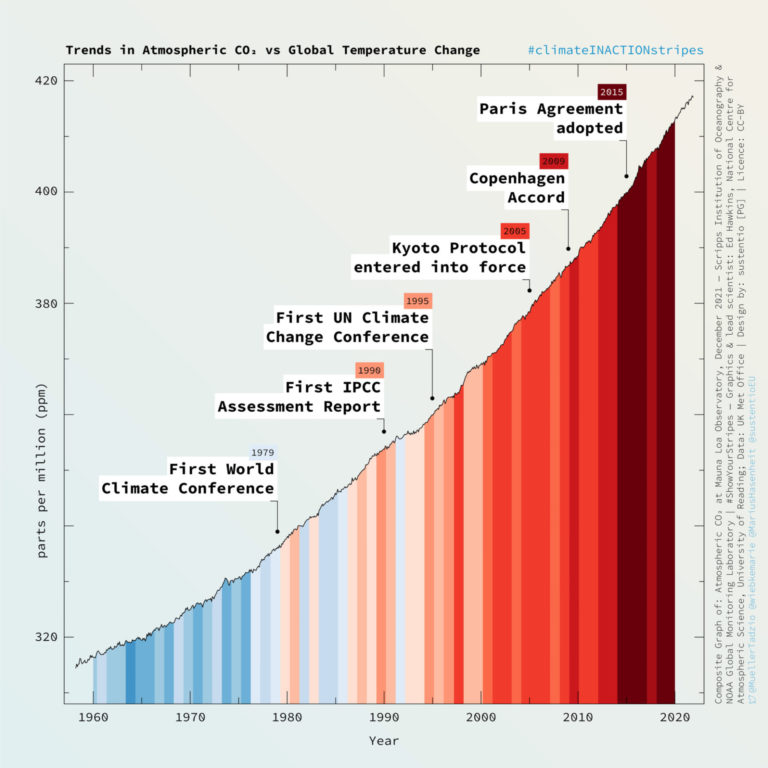

In New Zealand, half of our greenhouse gas emissions come from agriculture. This is more than all transport, power generation and manufacturing industries combined. Clearly the single biggest change an individual can make is therefore to reduce meat and dairy consumption. A shift from animal to plant-sourced protein would give us a 37% better chance of keeping temperature rise under 2℃ and an almost 50% better chance of staying below 1.5℃ – the targets of the Paris agreement.

Best of all, this can be done right now, at whatever level you can manage, and there are many people taking this step.

One aspect that is often overlooked is that carnivorous pets (mainly dogs, cats) consume lots of meat, with all the associated impacts described above. A recent US study concluded that dog and cat ownership is responsible for nearly one third of the environmental impacts associated with animal production (land use, water, fossil fuels). So ideally, if you’re getting a new pet, go for something herbivorous.

Buy locally, eat seasonally

Buy local produce, whether it’s food grown locally or goods manufactured locally rather than imported from overseas. Goods that are transported around the world by sea account for 3.3% of global carbon dioxide emissions and 33% of all trade-related emissions from fossil fuel combustion, so reducing our dependence on imports makes a big difference to our overall carbon footprint.

Car use is a problem because we all enjoy the personal mobility cars provide. But it comes with an excessively high carbon cost. Using public transport where possible is, of course, preferable, but for some, the lack of personal freedom is a big disadvantage, as well as the sometimes less than perfect transit networks that exist in many parts of the country.

One alternative for many people looking to commute short distances might be an e-bike but think of it as an alternative to your car rather than a replacement for your bike. For those looking to replace their car, buying a hybrid or full-electric model would be the best thing from an emissions perspective, even if the production of the cars themselves isn’t entirely without environmental problems.

New Zealand’s network of electric vehicle (EV) chargers is growing rapidly, but generally speaking, it is easiest to charge at home if you’re doing daily commutes. This becomes economical if you have an electricity supplier offering a special low rate for EV charging.

On the subject of electricity, an easy and quick way to reduce your carbon footprint is to switch to a supplier that generates electricity only from renewable sources. In New Zealand, we have an abundance of renewable options, from solar, wind and hydro.

Plant trees

Planting trees requires having some space, but if you have land available, planting trees is a great way to invest in longer-term carbon sequestration. There is a lot of variability between species, but as a rule of thumb, a tree that lives to 40 or 50 years will have taken up about a ton of carbon dioxide.

Read more:

Climate explained: why plants don’t simply grow faster with more carbon dioxide in air

Air travel is, for many of us, an essential part of our work. There is some progress in the field of aviation emissions reductions, but it is still a long way off. In the short term, we have to find alternatives, whether that is in the form of teleconferencing or, if travel is essential, carbon offsetting schemes (although this is far from a perfect solution, unfortunately).

Vote for climate-aware politicians and council representatives. These are the people who have the power to implement changes beyond the scope of individual actions. Make your voice heard through voting, and by contributing to discussion and consultation processes.

Community initiatives such as tree planting or shared gardens, or just maintaining wild spaces are ideal for carbon sequestration. This isn’t just because of the plants these spaces accommodate, but also because of the soil. Globally, soil holds two to three times more carbon than the atmosphere, but the ability of soil to retain this depends on it being managed well. Generally speaking, the longer and more densely planted an area of soil is, the better it will sequester carbon.

How to cope

One of the frustrations is the realisation that climate change is not something that can be left to politicians to deal with on our behalf. The urgency is simply too great. The responsibility has been implicitly devolved to the individual, without any prior consent.

Read more:

The rise of ‘eco-anxiety’: climate change affects our mental health, too

But individual actions are massively important in two ways. First, they have an immediate impact on our total carbon footprint, without any of the inertia of political machinations. Secondly, by adopting and advocating for low-carbon life choices, individuals are sending a clear message to political leaders that a growing proportion of the voting population will favour policies that are aligned with similar priorities.

It is of course hard to stand your ground and stick with new lifestyle choices when you feel surrounded by people who choose not to change, or worse, actively mock and criticise. This is normal human psychology. People subconsciously tend to feel attacked if they see someone else making a so-called ethical or moral choice, as if they themselves are being judged, or criticised.

In the context of climate change, the science is so overwhelmingly clear, and the current and future impacts so manifestly important, that not to acknowledge this in a meaningful manner either reflects a lack of understanding or awareness, or is simply selfish. Rather than taking issue with those members of society, a more positive approach that can help you cope with the feeling of marginalisation is to actively seek out like-minded people.

Nick Golledge, Associate Professor of Glaciology, Victoria University of Wellington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

23 Comments

Pingback: ไพ่เสือมังกร

Pingback: เว็บแทงบอล เชื่อถือได้ สำหรับสายกีฬา

Pingback: full service wedding planner Thailand

Pingback: ผู้ผลิต AdBlue รายแรกของประเทศไทย

Pingback: เรียนต่อจีน

Pingback: Diyala/baqubah/university/universal

Pingback: ทดลองเล่นสล็อต pg

Pingback: อาชีพสร้างรายได้

Pingback: Auckland painting service

Pingback: http://thirddaychruch.com/exploring-the-features-and-benefits-of-pocket-4/

Pingback: George

Pingback: เลขเด็ด987

Pingback: รับผลิตสปริง

Pingback: gubet

Pingback: chadabet

Pingback: รับติดตั้งระบบระบายอากาศ

Pingback: https://www.tehnohack.ee/avaliacao-do-aplicativo-mostbet-9/

Pingback: pg slot auto

Pingback: นำเข้าสินค้าจากจีน

Pingback: ufa777

Pingback: โคมไฟ

Pingback: altogel

Pingback: ufa11k