Darren R. Reid, Coventry University

When Fox News called the state of Arizona for Joe Biden, it sent shockwaves through Donald Trump’s campaign team. Since 1952, the state had only voted for a Democrat nominee once before. But as the counting in the state moved into its final stage the narrow nature of Joe Biden’s victory there started to become apparent. With an advantage of fewer than 12,000 votes, Biden could not have taken the state without Navajo voters.

Native Americans have had a significant, albeit little reported, impact on both the life and presidency of Donald J. Trump – and he upon them. Over the four years of his presidency, Trump has sought revenge for business losses he sustained from Native American casinos; turned the word “Pocahontas” into a racial slur, and denied tribal lands to Native American peoples in the east. But at times he also courted the political power of Native American communities.

His relationship with Indian Country is complex and, at times, contradictory, but it is also an important aspect in understanding his political life.

A war on Native American casinos

Trump’s antagonistic relationship with Indian Country began early. Despite having invested heavily in the gambling industry, his east coast casinos struggled to turn a profit. His gambling business had grown rapidly in the 1980s, driven by cash injections from his father, Fred Senior, but profitability was elusive. By the early 1990s, even the financial support of his father was proving insufficient to keep the businesses viable. In 1992, Trump’s casino business filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy. By contrast, Native American casinos – often operating in similar locations to Trump’s own – appeared to be flourishing.

Trump did not respond well to the apparent success of his rivals and, in 1993, he launched a series of attacks upon Native American gambling interests. Appearing on the radio, he attacked the notion of tribal sovereignty: “All of a sudden … they call it a nation. This great sovereign nation, the Indian tribes. All of a sudden, it’s nations.”

As he went on, Trump attacked mixed-race Indigenous identities. When host, Don Imus, commented that “[a] couple of these Indians up in Connecticut look like Michael Jordan”, Trump responded: “I think if you’ve ever been up there, you would truly say that these are not Indians.”

Trump also linked Native American casinos with criminality, as he would later do to Mexican immigrants: “A lot of the reservations are being, in some people’s opinion, at least to a certain extent, run by organised crime … as you can imagine.”

This wasn’t a one-off bluster. It was part of a coordinated – albeit far-fetched – effort to cripple the perceived advantages enjoyed by his Native American competitors. Trump later appeared in front of the bipartisan Native American Affairs Committee where he amplified his attacks. He told the committee: “You have got to check every supplier going into that Indian reservation … because this will be the biggest crime problem in this country’s history.”

Trump railed, in particular, against Native American tax exemptions, which he claimed were “unfair and don’t treat Native Americans equally.” As a private citizen, however, Trump’s attacks carried little weight and the Native American Affairs Committee declined to take his flawed protestations seriously.

In the White House

By the time Trump ascended to the White House, he was in a position to settle old scores. In 2019, and seemingly out of nowhere, Trump tweeted against the H.R.312 – Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe Reservation Reaffirmation Act, which would reaffirm that the reservation lands awarded to the Mashpee Wampanoag. The following year, he successfully rescinded the reservation status of 300 acres of their lands on which the band had been planning to build a $1 billion casino. The Trump administration was a dangerous time for the president’s old Indigenous rivals on the east coast.

It was also a difficult time for those Native Americans whose activism or existence made problems for Trump. The defeat of the Keystone XL project has been one of the great successes of Native American activism, with the US army and, ultimately, the Obama administration calling a halt to the project in the face of widely reported Indigenous protests. Despite Trump ordering that work on the pipeline recommence, little headway was made.

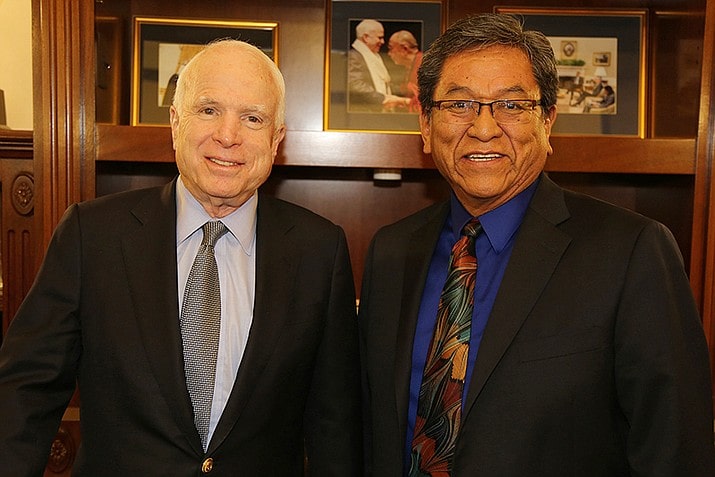

Barack Obama with representatives of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the St. Regis Mohawk Tribe and the Navajo Nation at the 2015 White House Tribal Nations Conference in Washington. EPA/Michael Reynolds

As a result, Trump began to host meetings with sympathetic Native American leaders, making the case that the federal government was robbing Indigenous communities of the opportunity to exploit – and profit from – reserves of natural resources. Throughout the 2018 and 2019, the Trump administration made a point of courting Native American voters as they developed this counter-narrative.

Despite this, Trump continued to mock Native Americans of mixed-race descent. In his many attacks on Senator Elizabeth Warren, he used “Pocahontas” as a slur. East coast bands were one of Trump’s favourite targets. He frequently referenced the “blood quantum” – an archaic system which measures racial purity in Native Americans, making determinations about cultural continuity, community, and identity legitimacy based on biology.

Native American supporters of Trump could potentially fare well under his administration. But many others, particularly those who did not fit the president’s image of what a Native American should be – such as the Mashpee Wampanoag – faced existential challenges instead.

The 2020 election

The Navajo – like all Native American peoples – are diverse, with many competing political interests. There is sizable support for Trump and the Republicans among them, but the weight of support they offered in 2020 heavily favoured Joe Biden and Kamala Harris.

An early report in the Navajo Times of an 89% Navajo turnout and 97% support for the Democratic ticket, widely shared online and on social media, proved inaccurate. But despite this, the Navajo vote remained critical for Biden in Arizona. Between 60% and 90% of voters supported the former vice president and turnout ranged from 67% to 81%, depending upon the precinct.

While not as headline-friendly as the originally reported figures, they nonetheless demonstrate that the Navajo were instrumental in securing Arizona for Biden. Without the Navajo vote, Biden would not have taken the state.

Considering that news organisations such as CNN do not even acknowledge Native Americans in their analysis, this should come as an important reminder to observers, journalists, pundits, and political scientists that continuing to ignore the country’s Indigenous peoples is, at best, a highly problematic omission of key data and, at worst, racism by omission.![]()

Darren R. Reid, Assistant Professor, History, Coventry University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

12 Comments

Pingback: AR 15 Trigger

Pingback: ayahuasca tea etsy

Pingback: valorant cheats

Pingback: sex bao dam

Pingback: sbobet

Pingback: bos dultogel

Pingback: tải go88

Pingback: eBET

Pingback: Diyala/baqubah/university/universal

Pingback: เว็บแทงบอลเชื่อถือได้

Pingback: สล็อตเว็บตรง ฝากถอนวอเลท ยิ่งปั่นโบนัสยิ่งแตก

Pingback: ข้อดีของเว็บ Heng888