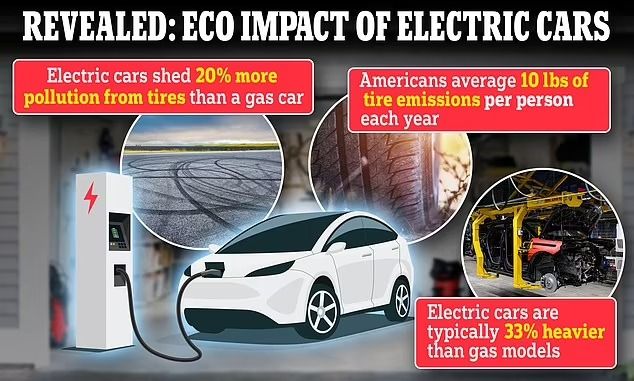

Electric cars offer no solution; their tires shed 20% more microplastic due to 33% heavier weight and faster acceleration.

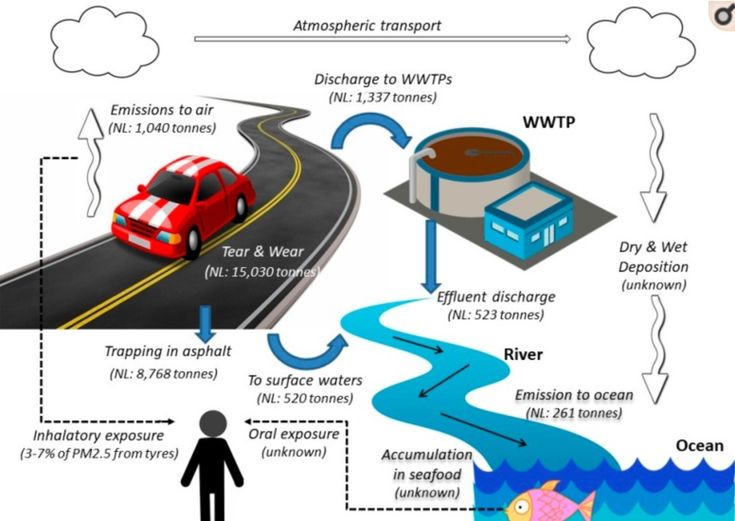

In Switzerland, tire abrasion is the largest source of microplastic in the environment (8,900 tonnes per year).

The problem with tire wear particles is the same as for pesticides, says Ursula Schneider Schüttel, president of Switzerland’s oldest nature conservation group, Pro Natura. “They are everywhere in the environment, and we can’t control where they go.” While tailpipe and brake-dust emissions have been falling in recent years, those for tire particles have been rising, driven by the trend for larger, more powerful cars.

Henry Obanya, University of Portsmouth

Every year, billions of vehicles worldwide shed an estimated 6 million tonnes of tire fragments. These tiny flakes of plastic, generated by the wear and tear of everyday driving, eventually accumulate in the soil, rivers, lakes, and even in our food. Researchers in South China recently found tyre-derived chemicals in most human urine samples.

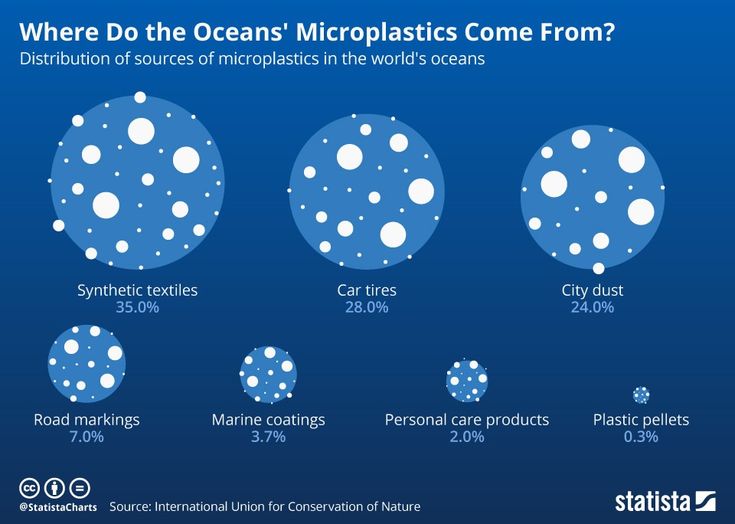

Tire particles are a significant but often overlooked contributor to microplastic pollution. They account for 28% of microplastics entering the environment globally.

Despite the scale of the issue, tire particles have flown under the radar. Often lumped in with other microplastics, they are rarely treated as a distinct pollution category, yet their unique characteristics demand a different approach.

We urgently need to classify tire particles as a unique pollution category. In our recent international study, colleagues and I found that this approach would drive more focused research that could inform policies designed to mitigate tire pollution. It could also help ordinary people better understand the scale of the problem and what they can do about it.

Right now, delegates are meeting in South Korea to negotiate the first global plastics pollution treaty. While this landmark agreement is poised to address many aspects of plastic pollution, tire particles are barely on the agenda. Given their significant contribution to microplastics, recognizing tire pollution as a unique issue could help unlock targeted solutions and public awareness. This is what we need to address this growing environmental threat.

Hundreds of chemical additives

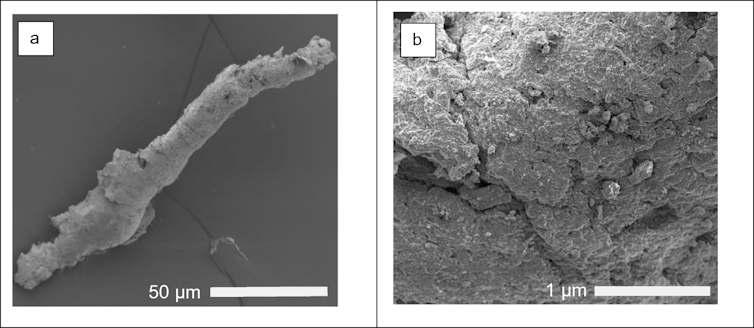

Tyre particles tend to be made from a complex mix of synthetic and natural rubbers and hundreds of chemical additives. This means the consequences of tire pollution can be unexpected and far-reaching.

For instance, zinc oxide accounts for around 0.7% of a tire’s weight. Though it is essential for making tires more durable, zinc oxide is highly toxic for fish and other aquatic life and disrupts ecosystems even in trace amounts.

Another harmful additive is a chemical known as 6PPD, which protects tires from cracking. When exposed to air and water, it transforms into 6PPD-quinone, a compound linked to mass fish die-offs in the US.

Heavy vehicles, more pollution

We know that heavier vehicles, including electric cars (which have hefty batteries), wear down their tires faster and generate more microplastic particles. Car industry experts Nick Molden and Felix Leach say that, as weight is crucial to a vehicle’s environmental impact, manufacturers should be targeted with weight-based taxes under a “polluter pays” principle. This could encourage lighter vehicle designs while motivating consumers to make greener choices.

There are many questions we still need to investigate. For instance, we still don’t know how far these tyre particles disperse, or exactly where they are accumulating. To assess their full ecological impact, we need more detailed information on which tire additives are most toxic, how they behave in the environment, and which species are most at risk (some salmon species are more sensitive to 6PPD-quinone than others, for example).

In the longer term, standardized methods will be crucial to measure tire particles and create effective regulations.

We need global action

Regulatory frameworks, such as the EU’s upcoming Euro 7 emissions standard (which targets vehicle emissions), provide a starting point for controlling tire emissions. But additional measures are needed.

Innovations in tire design, such as eco-friendly alternatives to zinc oxide and other materials like 6PPD, could significantly reduce environmental harm. Establishing a global panel of scientific and policy experts, similar to ones that already exist for climate science (known as the IPCC) or biodiversity (IPBES), could further coordinate research and regulatory efforts.

Crucially, we must classify tire particles as a distinct pollution category. Compared to conventional microplastics, tire particles behave differently in the environment, break into unique chemical compounds, and present distinct toxicological challenges.

With more than 2 billion tires produced each year to fit ever-heavier and more numerous cars, the problem is set to escalate. The environmental toll will only increase unless we recognize and target the specific problem.

Measures like weight-based taxation and eco-friendly tire innovations would reduce tire pollution and pave the way for more sustainable transportation systems. The question isn’t whether we can afford to act; it’s whether we can afford not to.

Henry Obanya, PhD Candidate, Ecotoxicology, University of Portsmouth

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.