I wrote this article 8 years ago when the consensus was 35C & high humidity was our “Wet Bulb Limit”

More recent science has it edited to 31C!

1500 dead at the Haj our most recent example!Assalamu Alaikumhttps://t.co/lOv0uMBFF0

— kevin hester (@iconickevin) June 28, 2024

“Wet bulb” event in Texas yesterday. This is where the heat and humidity is so high that your sweat will not evaporate. This makes it physically impossible for your body to cool itself outdoors.

Thankfully @GovAbbott has outlawed rest and water break mandates for workers. pic.twitter.com/jlOIMD5xFj— AtheistTexan (@TriTexan) June 28, 2024

We need a scarier term for Wet Bulb because I’ve tried explaining it to a few people around me, and they do not seem to understand.

Susan Yeargin, University of South Carolina

When summer starts with a stifling heat wave, as many places are experiencing in 2024, it can pose risks for just about anyone who spends time outside, whether runners, people who walk or cycle to work, outdoor workers, or kids playing sports.

Susan Yeargin, an expert on heat-related illnesses, explains what everyone should think about before spending time outside in a heat wave and how to keep yourself and vulnerable family members and friends safe.

What risks do people face running, walking, or working outside when it’s hot?

The time of day matters if you’re going for a run, walking, or cycling to work during a heat wave. Early risers or evening runners face less risk – the Sun isn’t as hot, and the air temperature is lower.

But if your normal routine is to go for a run midmorning or over lunch, you should probably reconsider exercising in the heat.

Almost everywhere in the U.S., the hottest part of the day is between 10 a.m. and 6 p.m. The body will gain heat from both the air temperature and solar radiation. The ground also heats up, so you’ll feel more heat rising from the asphalt or grass.

Add humidity to the mix, which will also affect your body’s ability to dissipate heat through sweat.

Don’t forget that the body also generates internal heat when you’re active, whether running or even mowing your lawn. When it’s warm to hot outside, you increase your heat gain through that exertion. The harder someone runs or cycles, the more heat they’re generating.

Outdoor workers on farms, construction sites, or even walking dogs are often in the heat longer and have less flexibility for breaks.

Do our bodies eventually adapt to summer heat?

It takes the typical person about two weeks to fully acclimate to higher temperatures. During that time, the body makes amazing adaptations to handle the heat.

Your sweat rate improves, dissipating heat more effectively. Your plasma volume expands so more blood flows through your body, so the heart doesn’t have to work as hard. Because your cardiovascular system is more efficient, your body doesn’t heat up as much. You also retain salt a bit better, which helps you keep water in your body.

That doesn’t mean you’re ready for even higher temperatures or extreme heat. Even if you’re acclimatized to 80-degree weather, you might not be ready for a 95-degree heat wave. Early-season heat waves and high humidity can reach a level people haven’t adapted to handle yet. And some combinations of heat and humidity are too much for anyone to spend time safely.

Are young children and older people at higher risk in the heat?

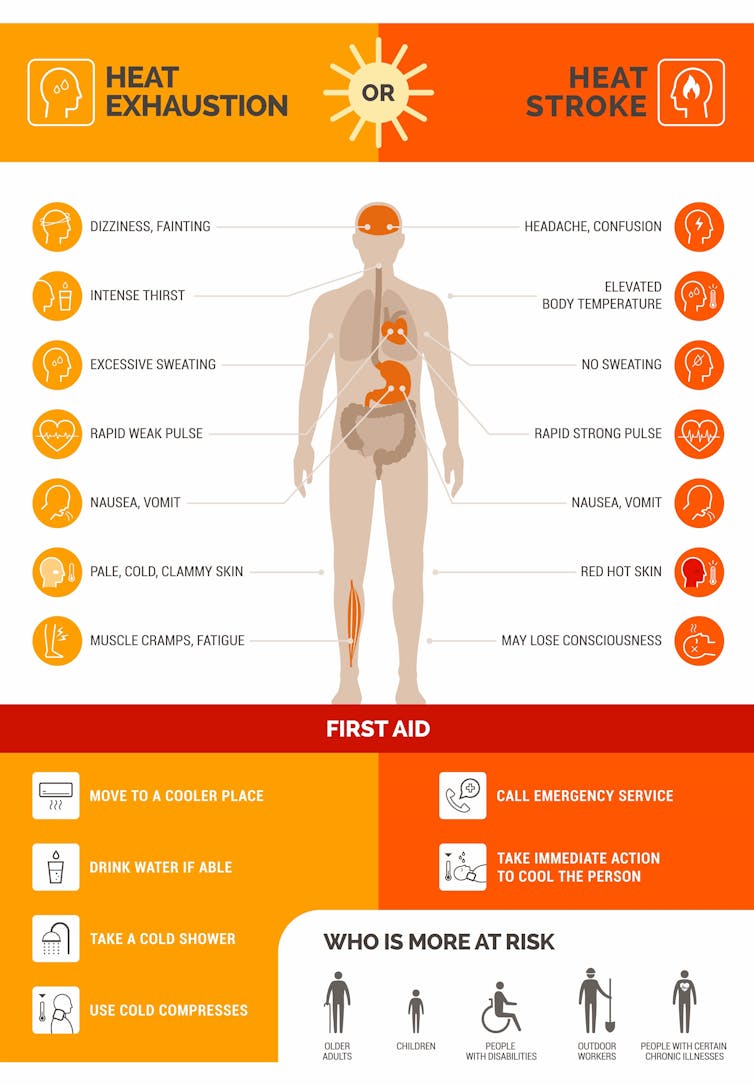

The cardiovascular system in older adults isn’t as flexible and powerful as it used to be, so it doesn’t operate as efficiently, and sweating mechanisms decrease. That leaves older adults at greater risk for illnesses such as heat exhaustion or heat stroke.

Their thirst mechanism may also not function as well, leaving them more likely to become dehydrated. Some older adults are also less willing or able to seek out cooling centers than younger people.

Ohio Department of Aging.

Children might take a few more days to acclimatize than adults. They’re also more dependent on skin heat loss than sweating, so their skin can get red and flushed-looking.

However, children are probably better at complaining about feeling too hot or not feeling well, so listen to them and help them seek out cooler areas. They might not realize that they can take a break during soccer practice or that they should come in from the beach.

What are your top heat safety tips?

Be smart about the time of day you’re active: People love their routines, but you need to get the workout, yard work, and other outdoor activities done early in the day or late in the evening. Avoiding the hottest parts of the day is the smartest way to prevent heat illnesses. When outside and the Sun is up, seek places with shade.

Have good hydration habits: Don’t ignore thirst – it’s your body telling you something. Hydration increases your plasma volume to help your heart work less and decreases your overall risk for heat illnesses. Your brain and muscles are also composed of water, so if your body senses that you don’t have enough water, it will start to sacrifice other things, including how much you’re sweating.

Listen to your body: When you need to be outside to work or play, your body will give you cues regarding how it’s handling the heat. If you don’t feel well, feel hot, or can’t seem to push harder, your body is telling you to slow down, add extra breaks, or get out of the situation.

AP Photo/Jeff Roberson

Make smart clothing choices: Wear light-colored clothing, which absorbs less heat than dark clothes. Short-sleeved shirts and shorts can also help prevent heat buildup or impair sweat evaporation.

Remember that helmets and sports equipment hold in heat: Construction workers often have to wear hard hats, but athletes don’t always need to practice with shoulder pads and helmets, especially in high heat. To help workers, companies are being pushed to follow health safety guidelines, such as providing cooling stations and hydration breaks.

Get a good night’s sleep: Heat exposure one day can affect your risk the following day. If you can sleep in air conditioning and get a good night’s sleep, that may help decrease the risk of heat illness.![]()

Susan Yeargin, Associate Professor of Athletic Training, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.