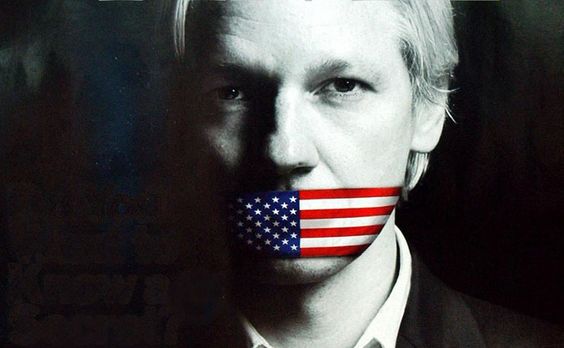

The outrageous part of the UK’s years-long “trial” to condemn Julian Assange to die in an American dungeon is that the victim of his “crime” (journalism) is a state rather than a person—the definition of a political offense, which the US-UK extradition treaty explicitly forbids.

Edward Snowden

Jeremy Corbyn speaks to @SkyNews outside court as Julian Assange hearing concludes

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) February 21, 2024

On Assange: “That’s what a journalists job is, to hold those in power, elected politicians and eveyone else to account, we have got to protect journalists” #FreeAssange pic.twitter.com/mEd9xGN2L7

Julian Assange’s extradition is being sought for such revelations as the ‘Collateral Murder’ gunning down of civilians including two Reuters journalists – he faces a 175 year sentence if extradited for his publishing

UK Court hearing concludes Wed 21 Feb, London #FreeAssange pic.twitter.com/jveiM1YFUU — WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) February 20, 2024

To date Julian Assange has spent 1771 days in a UK prison for publishing which revealed war crimes and human rights abuses

Assange has spent more than 13 years detained in one form or another

If extradited to the US he faces a 175 year sentence in conditions the UN’s torture… pic.twitter.com/P3QPpDiPsT

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) February 21, 2024

Holly Cullen, The University of Western Australia

On February 20 and 21, Julian Assange will ask the High Court of England and Wales to reverse a decision from June last year allowing the United Kingdom to extradite him to the United States.

There, he faces multiple counts of computer misuse and espionage stemming from his work with WikiLeaks, publishing sensitive US government documents provided by Chelsea Manning. The US government has repeatedly claimed that Assange’s actions risked its national security.

This is the final avenue of appeal in the UK, although Stella Assange, Julian’s wife, has indicated he would seek an order from the European Court of Human Rights if he loses the application for appeal. The European Court, an international court that hears cases under the European Convention on Human Rights, can issue orders that are binding on convention member states. In 2022, an order from the court stopped the UK from sending asylum seekers to Rwanda pending a full review of the relevant legislation.

The extradition process has been running for nearly five years. Over such a long time, it’s easy to lose track of the sequence of events that led to this. Here’s how we got here and what might happen next.

Years-long extradition attempt

From 2012 until May 2019, Assange resided in the Ecuadorian embassy in London after breaching bail on unrelated charges. While he remained in the embassy, the police could not arrest him without the permission of the Ecuadorian government.

In 2019, Ecuador allowed Assange’s arrest. He was then convicted of breaching bail conditions and imprisoned in Belmarsh Prison, where he remained during the extradition proceedings. Shortly after his arrest, the United States laid charges against Assange and requested his extradition from the United Kingdom.

Assange immediately challenged the extradition request. After delays due to COVID, in January 2021, the District Court decided the extradition could not proceed because it would be “oppressive” to Assange.

The ruling was based on the likely conditions that Assange would face in an American prison and the high risk that he would attempt suicide. The court rejected all other arguments against extradition.

The American government appealed the District Court decision. It provided assurances on prison conditions for Assange to overcome the finding that the extradition would be oppressive. Those assurances led to the High Court overturning the order stopping extradition. Then, the Supreme Court (the UK’s top court) refused Assange’s request to appeal that ruling.

The extradition request was passed to the home secretary, who approved it. Assange appealed the home secretary’s decision, which a single judge of the High Court rejected in June 2023.

This appeal is against that most recent ruling and will be heard by a two-judge bench. These judges will only decide whether Assange has grounds for appeal. If they decide in his favor, the court will schedule a full hearing of the merits of the appeal. That hearing would come at the cost of further delay in the resolution of his case.

Growing political support

Parallel to the legal challenges, Assange’s supporters have led a political campaign to stop the prosecution and the extradition. One goal of the campaign has been to persuade the Australian government to argue Assange’s case with the American government.

Cross-party support from individual parliamentarians, led by independent MP Andrew Wilkie, has steadily grown. Over the past two years, the government, including the foreign minister and the prime minister, have made stronger and clearer statements that the prosecution should end.

On February 14, Wilkie proposed a motion in support of Assange, seconded by Labor MP Josh Wilson. The house was asked to “underline the importance of the UK and USA bringing the matter to a close so that Mr Assange can return home to his family in Australia.” It was passed.

In addition, Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus confirmed he had recently raised the Assange prosecution with his American counterpart, who has the authority to end it.

What will Assange’s team argue?

For the High Court appeal, Assange’s legal team is expected to argue again that the extradition would be oppressive and that the American assurances are inadequate. A recent statement by Alice Edwards, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture, supports their argument that extradition could lead to treatment “amounting to torture or other forms of ill-treatment or punishment.” She rejected the adequacy of American assurances, saying:

They are not legally binding, are limited in their scope, and the person the assurances aim to protect may have no recourse if they are violated.

The argument that extradition would be oppressive remains the strongest ground for appeal. However, it is likely Assange’s lawyers will also repeat some of the arguments that were unsuccessful in the District Court proceedings.

One argument is that the charges against Assange, particularly espionage, are political offenses. The United States–United Kingdom extradition treaty does not allow either state to extradite for political offenses.

Assange is also likely to re-run the argument that his leaks of classified documents were exercises of his right to freedom of expression under the European Convention on Human Rights. The European Court of Human Rights has never found that an extradition request violates freedom of expression. For the High Court to do so would be an innovative ruling.

The High Court will hear two days of legal argument and might not give its judgment immediately, but it will probably be delivered soon after the hearing. Whatever the decision, Assange’s supporters will continue their political campaign, supported by the Australian government, to stop the prosecution.![]()

Holly Cullen, Adjunct professor, The University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.