Israel-Hamas War: What political consequences for Joe Biden?

Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy, CY Cergy Paris UniversitéOn November 5, 2024, Americans will go to the polls to elect their next president. Traditionally, foreign policy doesn’t weigh much on the outcome of an American presidential election, but might the return of violence in the Middle East reverse this old trend?What is certain is that the war between Israel and Hamas is being followed very closely in the United States. While the Republican Party and all its primary candidates are unambiguously on Israel’s side, the Democrats appear more divided. President Biden, traditionally aligned with the interests of the Hebrew state, has been playing a particularly difficult juggling act since October 7, seeking to protect and support Israel while not appearing insensitive to the more than 15,000 Palestinian victims caused by the Israeli response, according to Gaza’s health ministry. Joe Biden, a “Zionist in his heart,” forced to play a balancing act. Faced with the scale and nature of Hamas’ massacre on 7 October, which left 1,200 Israelis dead, Joe Biden drew parallels between these events and the Holocaust and the September 11th attacks. He immediately pledged his unconditional support to the Israeli government. This promise materialized not only in his visit to the Hebrew state on October 18, notwithstanding the political and security risks such a trip entailed, but also in the instruction to move navy warships closer to the country and send out artillery shells initially destined for Ukraine.This squares with President Biden’s historic ties with Israel. Notwithstanding periods of friction with Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu, whom he met extensively during his tenure as Barack Obama’s Vice President (2008-2016), Biden has an undeniable pro-Israeli bias, even describing himself as “Zionist in [his] heart.” In fact, he is more popular in Israel than in the United States and has received financial support from pro-Israeli groups throughout his career.The current crisis makes such a position tricky to maintain. On the one hand, the left wing of the Democrats accuses Biden of not taking sufficient account of Palestinian civilians in Gaza and being too complacent towards the Netanyahu government. And on the other, Republicans say he is responsible for the attack on Israel by being too complacent towards Iran, which supports Hamas. Aware of the stakes, and for only the second time in his presidency, President Biden addressed the nation in prime time from the Oval Office, making the case for military aid to both Israel and Ukraine. Speaking of an “inflection point in history,” he denounced anti-Semitism and Islamophobia, which are on the rise in the United States. He also reiterated his plea to Israelis not to be “blinded by rage” and to learn the lessons of an American overreaction to 9/11, referring to the Bush administration’s 2003 intervention in Iraq.A divided leftThe president’s balancing act occurs amid a growing number of protests and heated debates across the country. Thousands of demonstrators have poured into New York City and university campuses in solidarity with Palestine, while on Capitol Hill, Jewish peace activists called for an “immediate ceasefire” and justice for the Palestinians.

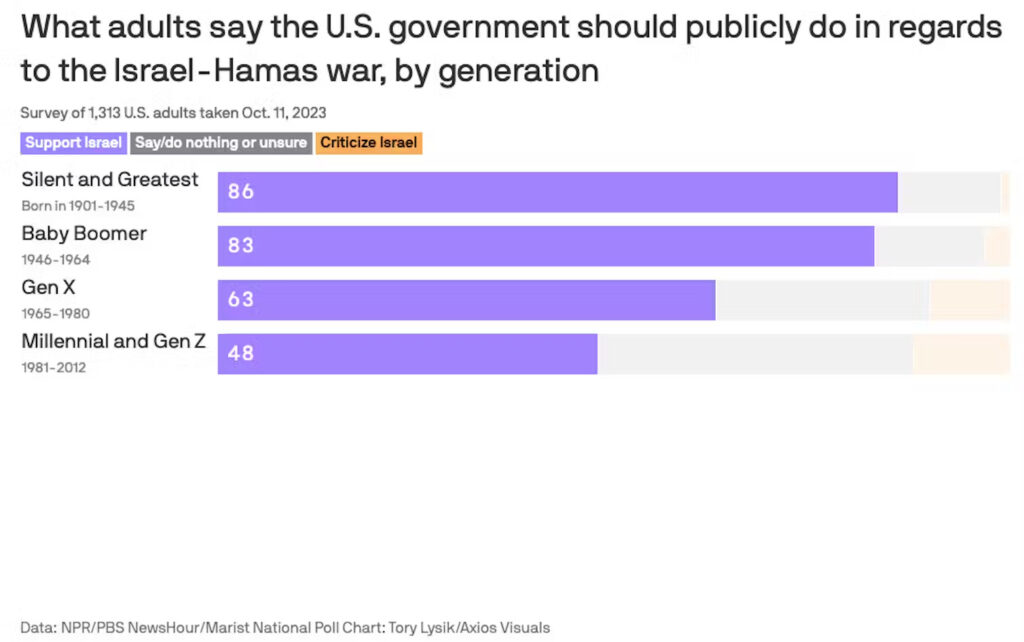

This is not entirely a surprise. For the last several years, the Democrats have been divided on the Israel question. The left wing of the party has become increasingly critical of both Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians and, more generally, of Netanyahu’s far-right government. This is reflected not only in divisions within the party but also in a shift in favor of the Palestinians among Democrats and Independents in opinion polls. The October 7 massacre has not reversed this trend. Moreover, the significant generational and racial differences are likely to remain as young and non-white liberals become more critical of public and armed support for Israel.

While in October, 72% of whites said the US should take a public stance supporting Israel in the war between Israel and Hamas, that figure dropped to 51% in the case of nonwhites, according to a poll by NPR. The Black community, for instance, has a long history of identification with the Palestinian cause, especially since the Six-Day War in 1967. This cause was promoted by radical organizations such as The Black Panther Party and The Nation of Islam, whose leader Louis Farrakhan is a notorious anti-Semite. It gained momentum on the left with Jesse Jackson’s presidential campaign in 1988. More recently, the death of George Floyd in 2020 had many young Americans, notably through Black Lives Matter, draw parallels between the structural violence and oppression of both Blacks in the USA and Palestinians in Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank.As for American Jews, traditionally more liberal, the unity they had once enjoyed in their opposition to Netanyahu has splintered in the face of this crisis. Some are demonstrating against the strikes on Gaza and calling for a ceasefire, while others highlight the victims of Hamas and feel abandoned by their left-wing allies.President Biden has increasingly taken this public opinion into account. As the death toll in Gaza has increased, his focus has shifted toward the suffering of a marginalized population trapped in Gaza. Biden has also secured humanitarian aid to Gaza at the Egyptian border and even temporary pauses in the fighting. His continuous refusal to demand a cease-fire, however, is unlikely to appease his critics, including those among Jewish-American intellectuals, legal scholars, or the Democratic party. Republicans (finally) unitedThe Republican Party, fractured on the issue of Ukraine, is united in its support for Israel. The first act of the new Republican House Speaker, Mike Johnson, was to pass a resolution in support of Israel for “whatever it needs” in its fight against Hamas, a resolution passed by an overwhelming majority despite a small group of (mostly) Democratic opponents. Following strong criticism from his rivals in the primaries, even Donald Trump backtracked after lashing out at Netanyahu and praising Hezbollah, calling it “very smart.” The vote for a $14.3b aid package to Israel, however, has been stalled by internal divisions over aid to Ukraine.There are several reasons behind the party’s unwavering support for Israel. One of them is the influence of the white evangelicals, an important voting bloc for Republicans. Most evangelicals, such as new house speaker Mike Johnson, read the events in Israel through a literal interpretation of biblical prophecy about the end times), and God’s promise to Abraham of a land for his descendants. To please this group, Trump moved the embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Another important element is the great ideological proximity between the MAGA Republicans and the far-right Israeli coalition in power in Israel. Finally, let us not forget there has been a growing Islamophobic sentiment among conservatives, especially since 9/11 – a sentiment nurtured and exploited by Trump. The former president has recently promised to renew the travel ban on nationals of several Muslim-majority countries and extend it to refugees from Gaza if he wins the presidency.How might this crisis impact the 2024 elections?Since the war broke out, public opinion has essentially remained divided along partisan lines. Moreover, with a few exceptions, such as the hostage crisis in 1979 or the War on Terror in 2004, foreign policy issues have rarely determined a national election since the Vietnam War. Even the relatively swift victory in Iraq in 1991 did not prevent George Herbert Walker Bush, who had the highest approval rate after the war, from losing the election 18 months later. What matters most to the American voter are day-to-day issues, particularly regarding the economy or social issues like abortion.However, the political landscape has changed tremendously in the last two cycles. 2024 could be a close election determined by only a handful of electors in a few swing states between two uniquely unpopular candidates. Even if a majority of voters broadly support Israel, Joe Biden might be in trouble if some non-white voters, like Arab-Americans and left-wing pro-Palestinian youth, protest against his stance by not turning out to vote in swing states. For example, a key state like Michigan, which Biden won in 2020 by a narrow margin of 150,000 voters, has a large Muslim population (estimated at 240,000) whose leaders are highly critical of Biden’s policy toward the Palestinians.The elections are a year away, and a lot can change between now and then. Much may depend on how the crisis evolves and what makes the headlines by then. The official campaign season has not even begun yet. In the meantime, in the face of rising isolationist sentiment, the American president will have to convince people that the United States is indeed the “indispensable nation” in the fight against tyrants and terrorists who threaten peoples and democracies. He will also have to demonstrate, as he said in his address to the nation, that Putin is as dangerous as Hamas. Above all, he will have to counter the image of a weakened US power, embodied by a president physically marked by his old age, at a time when voters seem more attracted by energy and strength than by experience and competence.![]()

Jérôme Viala-Gaudefroy, Assistant lecturer, CY Cergy Paris Université

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

A brief history of the US-Israel ‘special relationship’ shows how connections have shifted since long before the 1948 founding of the Jewish state

Bettmann via Getty Images

Fayez Hammad, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

In his first remarks after the Oct. 7, 2023, Hamas attacks on Israel, President Joe Biden affirmed the United States offered “rock solid and unwavering” support to Israel, “just as we have (done) from the moment the United States became the first nation to recognize Israel, 11 minutes after its founding, 75 years ago.”

Vowing to destroy Hamas, Israel has launched a war on Gaza that, as of the end of November, had killed more than 14,000 Palestinians. The fighting has also destroyed much of Gaza and displaced about 70% of its population.

Israel, with U.S. backing, has not heeded calls for an immediate cease-fire or U.N. demands to stop targeting civilians. The Biden administration appears to have played a key role in negotiating a temporary truce and an exchange of hostages and prisoners between Israel and Hamas.

I teach courses on Middle East politics and the Arab-Israeli conflict, which includes the interconnected Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the conflict between Israel and Arab states. The roots of the U.S.-Israel relationship predate 1948 and provide context for what has long been characterized as a “special” relationship between the two countries – one that now appears crucial to Israel’s prosecution of a war in Gaza.

During the Cold War, it was the perception in the U.S. that Israel’s strategic value served as justification for the special relationship. While Israel has its own interests regarding the Arab-Israeli conflict, a supportive Congress and American domestic lobbyists have presented them as consistent with those of the U.S.

The Bible, Christian Zionism, popular culture, memorialization of the Holocaust after 1967, and the shared approach in the U.S. and Israel toward the land and the indigenous populations have all led to the transformation of Jews and Israelis from “outsiders” to “insiders” in the U.S.

This cultural and political affinity is behind the U.S.’s current unconditional support for Israel, as well as the fact that the U.S. is seen in the region and beyond as deeply implicated in Israel’s actions.

But since President Harry Truman recognized Israel in 1948, presidential policies show that the U.S.-Israel relationship has not always been “rock solid.”

Pre-statehood: The United States and Zionism

With an Arab majority for more than a millennium until 1948, the territory then called Palestine was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1517 until Britain captured it during World War I.

The Zionist movement achieved a major objective in November 1917, when Britain issued the Balfour Declaration for strategic and religious reasons to support a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson endorsed this declaration, and the League of Nations sanctioned British administrative power over Palestine.

In Palestine, Britain used its administrative power, under what was called the Mandate over Palestine, to advance the Zionist project. The rise of Hitler and U.S. entry into World War II led American Zionists in 1942 to adopt the Biltmore Program, which called for unrestricted Jewish immigration to Palestine and for turning the territory into a Jewish state. The revelation of the full scale of Nazi atrocities boosted U.S. support for Zionism, effectively shifting the center of political Zionism from London to Washington.

The 1944 Democratic Party platform backed the “opening of Palestine to unrestricted Jewish immigration and colonization” and the creation of a Jewish state. But fearing damage to U.S. war efforts, President Franklin Roosevelt wrote to several Arab governments shortly before he died in 1945 that no action toward Palestine would be taken “which might prove hostile to the Arab people.”

Israel, the United States, and the Cold War

President Harry Truman was sympathetic to Zionism because of his evangelical Christian upbringing. He endorsed the 1947 U.N. Partition Plan for Palestine to create an Arab state and a Jewish state and, despite opposition from within the administration, recognized the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.

Truman, however, refused to send weapons to either side of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War because he viewed the conflict as a source of instability in the face of the emerging communist threat. In that war, 750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled, becoming refugees from the land that became Israel.

President Dwight Eisenhower also sought to prevent Soviet penetration into the Middle East and attempted to maintain impartiality toward the Arab-Israeli conflict. He even threatened to cut off all official and private aid and to expel Israel from the U.N. to force Israel’s withdrawal from Egyptian territory, the Sinai, in 1957.

The conflict and US-Israeli special relationship

President John F. Kennedy coined the term “special relationship” to describe the connection between the two countries. He hoped that in exchange for U.S. defensive weapons, Israel would support his plan, based on U.N. Resolution 194, which called for repatriation or compensation for the Palestinian refugees and allowed adequate inspections of its nuclear program. Israel accepted the weapons but refused to cooperate on the other issues, neither of which was discussed again.

President Lyndon Johnson viewed Israel as a strategic asset and sent it advanced offensive weapons. Johnson supported Israel’s attack on Egypt, Syria, and Jordan in the June 1967 war, when Israel first occupied the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Johnson also endorsed the November 1967 U.N. Resolution 242, which conditioned Israeli withdrawal on Arab states’ recognition of and entering into peace treaties with Israel. Israel’s swift victory transformed the U.S.-Israeli relationship, elevating Israel into a critical component of American Jewish identity and solidifying pro-Israel policies in Washington.

President Richard Nixon provided Israel with a massive increase in military and economic aid because he accepted uncritically Israel’s claim that the Soviets were the main cause of tension in the Middle East and because of the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. Generous aid packages have since become routine: In recent years, U.S. aid to Israel has been about US$3 billion to $4 billion annually, totaling almost $318 billion since World War II, including the value of weapons.

While President Jimmy Carter brokered the 1979 Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty, the Ronald Reagan administration later moved away from an active peace process and, within a Soviet-centered focus, signed with Israel memoranda on strategic cooperation, elevating the relationship to a new strategic level. The administration supported Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon, refused to label West Bank settlements as illegal, concluded with Israel and the U.S.’s first free trade agreement, and designated Israel in 1987 “a major non-NATO ally.”

President Bill Clinton brokered the Oslo Accords, in which Israel agreed to withdraw from areas in the West Bank and Gaza Strip and cede some control to a new political entity, the Palestinian Authority. But Clinton failed to achieve a permanent Palestinian-Israeli agreement, and his administration, according to one U.S. negotiator, acted as “Israel’s attorney, catering and coordinating with the Israelis at the expense of successful peace negotiations.”

The ‘peace process’ and the ‘war on terrorism’

In the wake of 9/11, President George W. Bush accepted Israel’s narrative that it was waging its own war on terrorism and its condition that a change of Palestinian leadership must precede any further negotiations. But neither Bush’s call for a Palestinian state nor the 2005 election of Mahmoud Abbas as president of the Palestinian Authority led to an agreement.

In 2006, the Bush administration pushed for and endorsed the participation of Hamas in Palestinian legislative elections. When Hamas won and formed a new government, both Israel and the U.S. refused to deal with it, imposed sanctions on the Palestinian Authority, and worked to widen the split between Hamas and Abbas’ Fatah party. Bush even supported a covert plan to spark a civil war between Palestinians, which led to a Hamas-Fatah military confrontation. That fight ended with Hamas’ takeover of Gaza, which led Israel to impose a blockade on Gaza in 2007.

President Barack Obama supported Israeli attacks on Gaza, which failed to eliminate Hamas’ military threat. Diplomatically, Obama was reluctant to get directly involved, while Israel continued to refuse to permanently freeze the building of new settlements.

President Donald Trump’s Abraham Accords and the recent discussions under the Biden administration to establish Israeli-Saudi diplomatic relations assumed that the Arab-Israeli conflict could be solved without solving the Palestinian conflict. But the current war challenges such an assumption and illustrates that current U.S. support for Israel is indeed “rock solid and unwavering.”![]()

Fayez Hammad, Lecturer in Political Science and International Relations, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

5 Comments

Pingback: Israel had no history only a criminal record. "From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free" - Bergensia

Pingback: Israel-Hamas war: What is Zionism? A history of the political movement that created Israel as we know it - Bergensia

Pingback: What if Jesus Christ was a Palestinian Jew who spoke Aramaic, a language in the same family as Hebrew and Arabic - Bergensia

Pingback: The International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled 'plausible' genocide by Israel in Gaza. - Bergensia

Pingback: Trump, Netanyahu, Keir Starmer and Western Media's Genocide Continues - Bergensia