Will the Norwegian Government survive the electricity price scandal? As soon as the new export cables were able to deliver, the new market conditions made its new market dynamics (imported prices); everyone wants green renewable low emission electricity, and no matter what quantity Norway can provide of it the demand is even higher resulting in a whole new price level for electricity in the southern parts of Norway.

In 2021 Norway increased production from hydro and wind power

Statnett is responsible for the operation of 17 power cables to other countries, including four to Denmark, one to the Netherlands (Norned), one to Germany (Nordlink – opened December 2020 in ordinary operation from March 31. 2021), and one to the United Kingdom (North Sea Link – operational for testing from October 1. 2021). In addition, Norway has onshore power lines to Russia, Finland, and Sweden.

In the license application for exchange cables to Germany and the United Kingdom, Statnett wrote that «an increase in the exchange capacity of 2800 MW will contribute to the average price in Norway increasing between approx. 2.5 and 4 øre / kWh ».

Elhub: Norwegian electricity production was at a record high in 2021. A total of about 157 TWh was produced, up from 154 TWh in 2021. 93 percent of this was accounted for by hydropower. Wind power accounted for approximately 12 TWh of electricity production. Electricity was also produced from heat (1.5 TWh) and solar (0.03 TWh). Net exports were reduced by about 3 TWh from 2020 to around 17 TWh in 2021. It was especially in the second half of the year that exports declined compared with last year. When electricity is transferred, something is lost on the way from producer to consumer. In 2021, this loss amounted to about 8 TWh (5%).

Germany’s energy consumption rising in a year with less wind

German market report 2021 by Clean Energy Wire

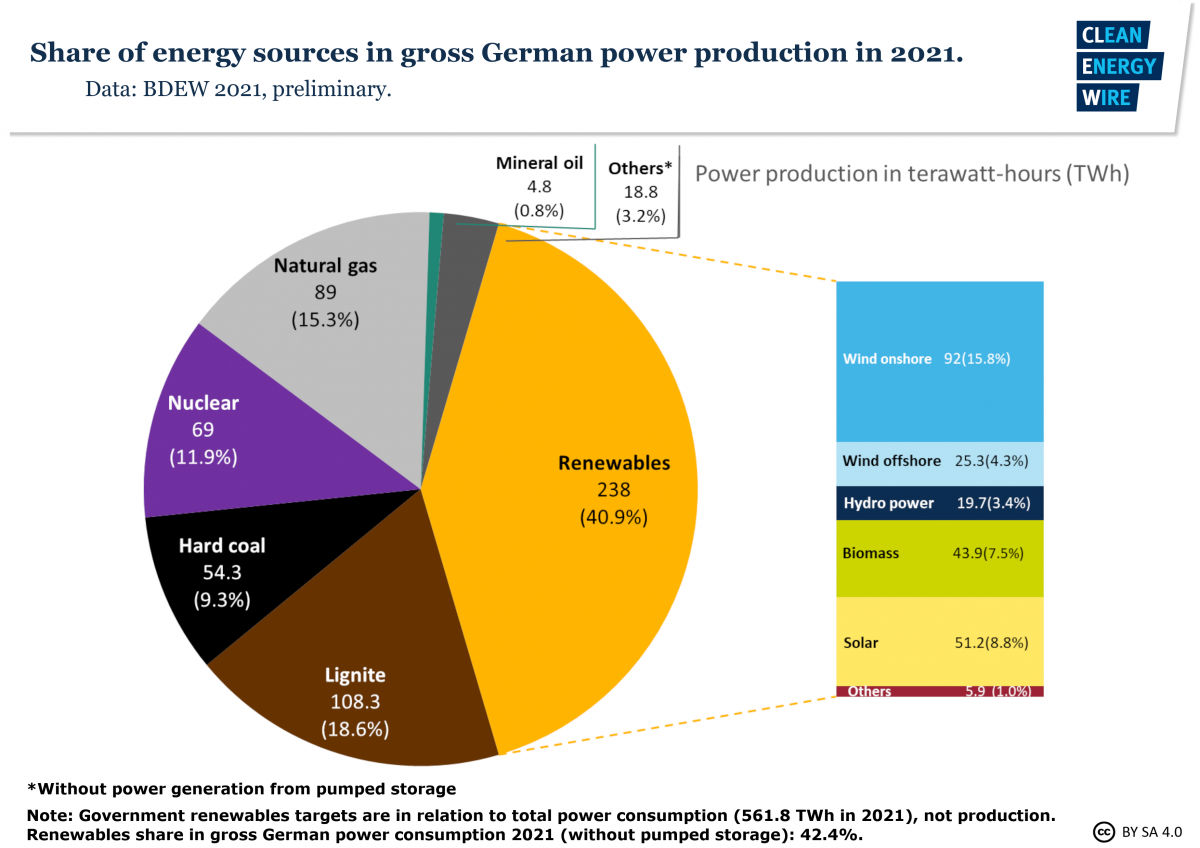

German power mix 2021: The new government wants to reach a renewable share of 80 percent in 2030.

Energy consumption in Germany has increased in 2021, as the economy recovered from the effects of the coronavirus pandemic and the country weathered a cold winter. At the same time, a year of depressed wind power production let the share of renewables in the country’s power mix shrink, while coal power made a strong comeback. The developments bode ill for the new German government’s plans to reduce energy use and boost renewables to record shares by 2030 – the same year it plans to end the use of coal. Energy industry representatives say the government’s plans are still feasible but will require resolute and swift action to succeed.

The consumption of energy in Germany has increased in 2021 compared to the previous year, while the share of renewable energy sources in power production was in decline, figures released by energy market research group AGEB and by energy industry lobby association BDEW have shown. Energy consumption increased by 2.6 percent (12,193 petajoule) compared to 2020 when economic activity was severely depressed due to the coronavirus pandemic, AGEB said, adding that primary energy consumption in the country still ranked significantly below pre-crisis levels from 2019, as pandemic effects could still be felt in 2021 and supply chain interruptions further obstructed economic recovery.

Very cold weather at the beginning of the year also contributed to higher energy use and, according to AGEB, accounted for most of the increase. On the other hand, price hikes on energy markets and in the European emissions trading system (ETS) “visibly slowed down the growth-driven rise in primary energy consumption”, the researchers said.

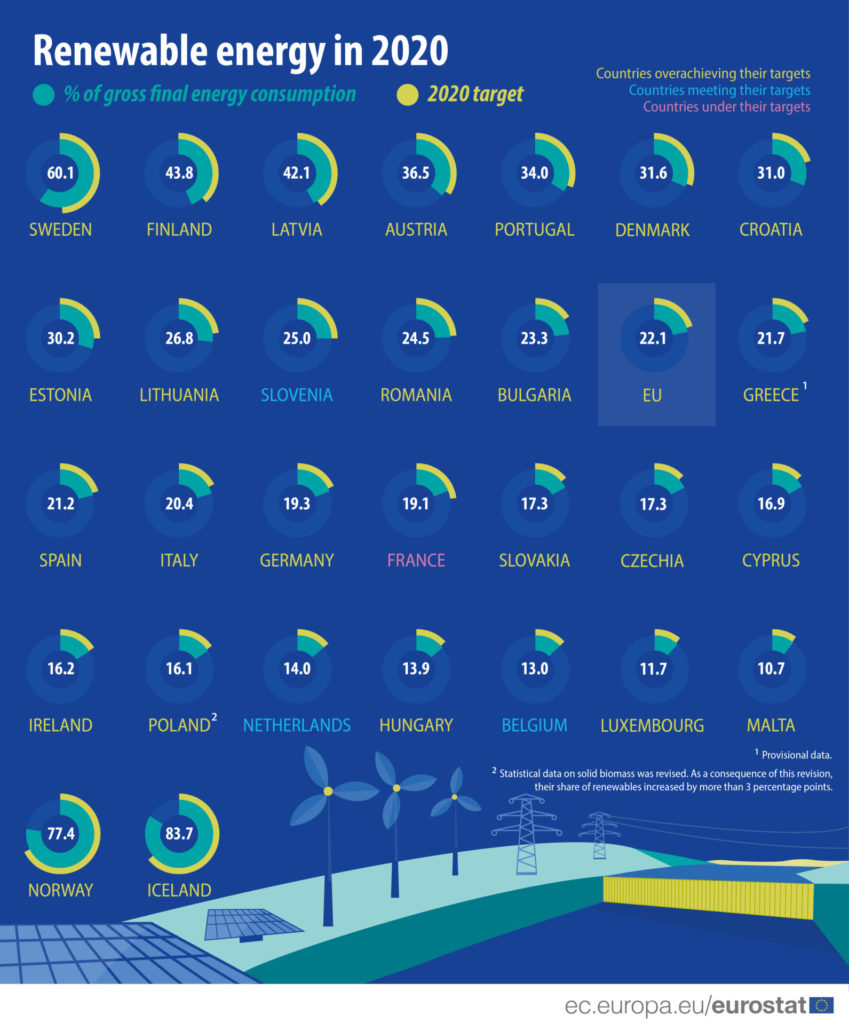

The increase in energy consumption and drop in renewable power production adds further urgency to the new government of chancellor Olaf Scholz to make good on its promise to ignite a booster in Germany’s energy transition. The Social Democrat’s (SPD) coalition with the Green Party and the Free Democrats (FDP) aims to reduce Germany’s emissions by 65 percent by 2030 and achieve a share of 80 percent renewables in electricity consumption in the same year. It also wants to “ideally” phase out coal-fired power production completely by the end of the decade.

Coal industry preparing phase-out despite increasing share in power system

In contrast to the government’s plans, coal power consumption increased markedly, with both hard coal and lignite use up by about 18 percent, whereas natural gas increased by only 4 percent. However, statistical effects played an important role in the year-on-year rise, meaning lignite use still was 5 percent lower than in 2019 and even 25 percent lower than 2018, according to the coal industry association DEBRIV. However, even though lignite plants had made a “remarkable contribution” to Germany’s supply security this year and domestic supply with fossil fuel would not be affected by price hikes like gas or oil, the increase in use in 2021 does not change the technology’s overall demise in Germany, DEBRIV head Thorsten Diercks said.

Nuclear power, which will be phased out completely in Germany by the end of 2022, saw an increase of more than 7 percent “due to higher demand, low output from renewables and the development of energy and CO2 prices”. The share of renewables in primary energy consumption fell from 16.5 percent in 2020 to 16.1 percent this year, mainly caused by a drop in wind power generation of about 10 percent due to unfavorable weather conditions.

As a result of the higher overall consumption and comparably weak renewables output, the country’s energy-related CO2 emissions this year are expected to be about 25 million tonnes (4%) higher than in 2020, AGEB said. Energy-related CO2 emissions account for about 85 percent of Germany’s total greenhouse gas emissions. Assuming that all other emissions remained unchanged, total greenhouse gas output would still remain well below pre-pandemic levels. The country would have reduced emissions by about 39 percent compared to 1990 levels.

New government must install 30 new wind turbines per week – energy industry

According to the energy industry lobby group BDEW, total energy sector emissions reached 247 million tonnes in 2021, less than the sector’s 2022 target of 257 million tonnes. In a long-term trend, CO2 emissions from the sector were falling despite the ups and downs caused by the pandemic, while wind power stayed the most important individual power source, BDEW head Kerstin Andreae said. However, the share of renewables in electricity production dropped from about 44 percent in 2020 to just under 41 percent this year, slightly more than in 2019. Andreae argued that the new government’s target of bringing the renewables share in power use to 80 percent by 2030 would still be feasible. “This can be done, even if it is very ambitious and requires a fast pace in the next years,” she said.

In order to reach the envisaged capacity of 200 gigawatts (GW) by the end of the decade, the government will face the challenge to add 15GW of solar PV capacity each year, almost three times the 5.8 GW added in 2021. The target of 100GW onshore wind power means that the number of turbines built each week must rise from currently 8 to about 30 if the modern installations are used, she added. The key for achieving this would be to reduce administrative hurdles: “Procedures have to be made more efficient and become digital wherever possible. And we need the required areas and skilled workers who put a faster energy transition into practice,” Andreae said.

Moreover, a faster expansion of grid infrastructure would be equally necessary to achieve the transition, as well as more gas power plants as a bridging technology before they are fully converted to green hydrogen use. She warned that taken together, about 40GW of secure nuclear and coal power supply would drop out of the system by 2030, meaning new energy infrastructure to adequately replace them needs to be fully operational in less than a decade. “Supply security is the guarantee we need to make sure the climate targets are accepted,” she said.

Andree Böhling of environmental action NGO Greenpeace called the jump in carbon emissions a “poisoned present” by the previous government of conservative Angela Merkel (CDU). Even if Scholz’s coalition is not to blame for the current situation, it will still have to come up with a response quickly, he argued. “Measures of an action program must tackle the root cause of rising emissions, meaning substantially higher coal use and growing power consumption,” Böhling said, calling for a ceiling on coal power use in the electricity system and ending coal use by 2030.

The UK’s nuclear output has plunged to its lowest level since 1982.

The 9% drop in 2021, due to retirements and outages at the UK’s aging reactors, contributed to a record 17 terawatt hour (TWh) fall in low-carbon electricity last year, with wind generation also falling 15%. The government aims to have a fully decarbonized power system by 2035 – but the latest figures show it is going in the wrong direction. The figures are based on a Carbon Brief analysis of data from BM Reports and the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

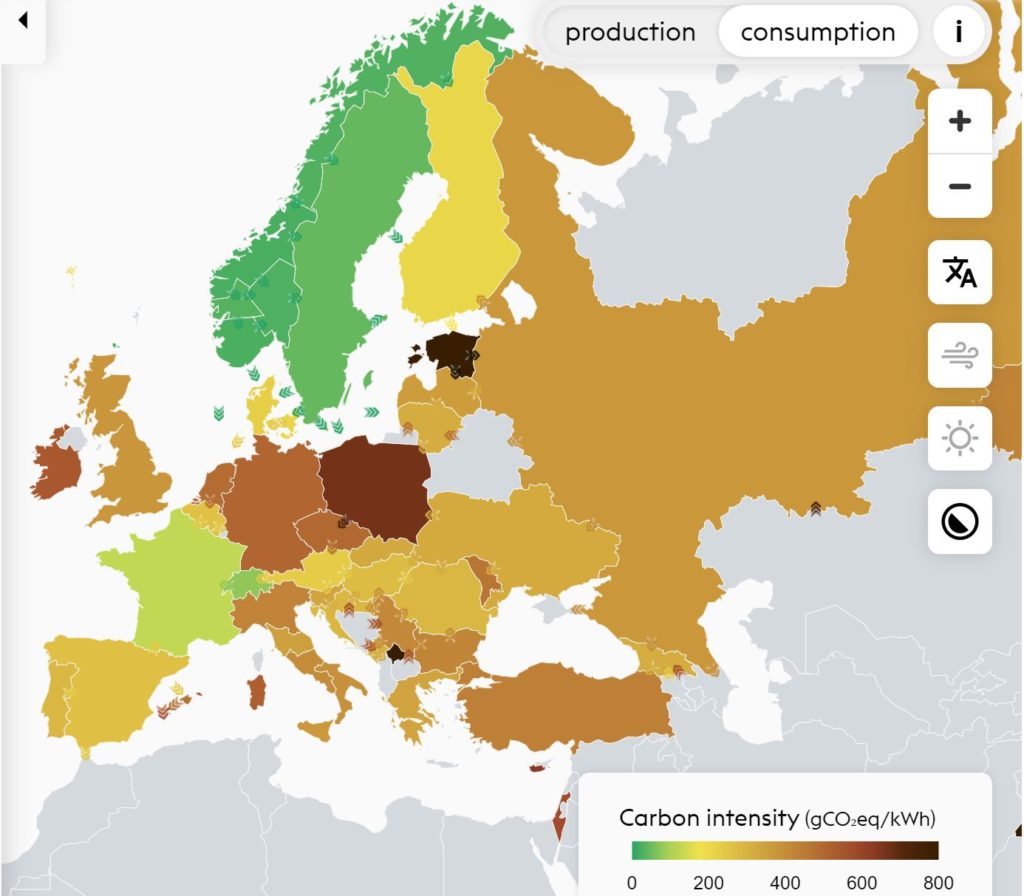

They show that the carbon intensity of electricity generation rose last year by nearly 10% to 199 grams of carbon dioxide (CO2) per kilowatt-hour (gCO2/kWh), up from a record-low 183gCO2/kWh in 2020.

This is because electricity generation from fossil fuels was some 9% higher than a year earlier, of which nearly 90% came from the higher gas output. Coal’s share remained below 2%, despite growing slightly compared with a year earlier, while gas increased its share from 34% to 37%.

Nevertheless – with demand barely recovering from coronavirus lockdowns in 2020 – low-carbon sources still generated more than half of UK electricity in 2021, including 19% from wind, 14% from nuclear, 12% from biomass, and 4% from solar.

Plunging nuclear

Many recent headlines have focused on Germany’s deliberate strategy to end its use of nuclear power, with three of its remaining six reactors having switched off at the start of the year.

Few, though, have noted the significant declines in countries including France and the UK – albeit forced rather than due to policy choices – as aging reactors come to the end of their lives.

Electricity generation from the UK’s nuclear power plants fell by another 9% in 2021 to just 46TWh, less than half the peak in 1998 and the lowest in nearly four decades.

This is shown in the figure below, which charts the expansion and subsequent decline of the UK’s nuclear output.

Electricity generation from nuclear power plants in the UK, terawatt-hours (TWh), 1920-2021. Source: BEIS and Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Joe Goodman for Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Electricity generation from the current UK nuclear fleet is set to decline further as the reactors reach their scheduled retirement, with all except Sizewell B in Suffolk due to close by 2030.

Two new reactors at Hinkley Point C in Somerset are due to come online later this decade and the government hopes to secure a deal for an identical plant at Sizewell C during this parliament. Together, these new nuclear plants would roughly replace current nuclear output. (The government is also supporting the development of small nuclear reactors, the first of which it hopes to see coming online in the “early 2030s”.)

Low-carbon low

The UK’s windfarms also had a challenging year in 2021, with generation falling by an estimated 15% – despite rising capacity – as a result of the lowest average wind speeds in a decade.

Reduced sunshine hours and below-average rainfall caused 9% and 26% drops in solar and hydro generation, respectively, with the reported capacity of both sources barely changing.

In combination with the decline in nuclear output, this means the UK’s low-carbon electricity generation saw its largest-ever one-year fall of 17TWh, shown in the chart below.

Top: Electricity generation from low-carbon sources and fossil fuels, TWh. Middle: Share of UK electricity by source, %, 1920-2021. Bottom: Generation by source, TWh, 1920-2021. Source: BEIS and Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Joe Goodman for Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Despite the record fall in 2021, low-carbon sources still generated more than half of UK electricity (51%), as the chart above shows, with fossil fuels making up 39% and imports another 8%. In part, this was due to the fact that demand barely increased from the lockdown-induced lows seen in 2020 (bottom panel).

Another contributor was two new interconnector cables – the North Sea Link with Norway and IFA2 with France – which helped boost electricity imports, despite a prolonged outage for the existing IFA1 cross-channel cable.

The remaining 3% of the mix in 2021 was from pumped hydro storage (1%) and other sources (2%), including the UK’s growing fleet of battery storage sites, as well as waste incinerators.

Changing mix

The chart below shows a more granular picture of UK electricity generation since 2010, with renewables broken down into its constituent parts.

It shows that increased generation from gas (dark blue, up 9%) and imports (red, up 37%) compensated for reduced low-carbon supplies in 2021.

UK electricity generation by source, terawatt-hours, 2010-2021. Source: BEIS and Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Joe Goodman for Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Notably, despite rising last year, gas generation remained some 8% below 2019 levels and well below previous highs, at nearly a third lower than the output from the fuel in 2010.

Similarly, the 12% bump in coal generation (black) left the fuel well below its 2019 figure and still at historically low levels. There were 90 full days without coal generation in 2021, Carbon Brief analysis shows, down from 180 days in 2020, but still above 83 in 2019 and 21 in 2018.

Combined generation from coal and gas last year, at 127TWh, was some 55% below 2010 levels. Meanwhile, imports reached their highest level on record, at 25TWh and 8% of the mix overall.

The chart also shows the stark reduction in wind generation in 2021 (light blue) as above-average wind conditions in 2020 gave way to the lowest average wind speeds in a decade.

Biomass grew by 2% to account for 12% of UK electricity in 2021, nearly a third of the total from all renewables. Some two-thirds of the biomass output is from “plant biomass”, primarily wood pellets burnt at Lynemouth in Northumberland and the Drax plant in Yorkshire. The remainder was from an array of smaller sites based on landfill gas, sewage gas, or anaerobic digestion.

The government’s advisory Climate Change Committee (CCC) says the UK should “move away” from large-scale biomass power plants, once existing subsidy contracts expire in 2027.

Using biomass to generate electricity is not zero-carbon and in some circumstances could lead to higher emissions than from fossil fuels. Moreover, there are more valuable uses for the world’s limited supply of biomass feedstock, the CCC says, including carbon sequestration and hard-to-abate sectors with few alternatives.

To be continued with the Nederlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Finland.

2 Comments

Pingback: Motvind Norge reports the management and owners of the Storheia and Roan wind power plants in Fosen - Bergensia

Pingback: sleep music