Francesca Moore

Nando Sigona, University of Birmingham

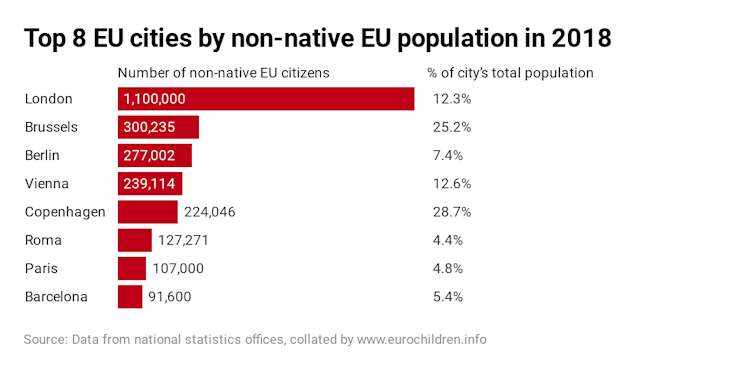

London is one of the capitals of the EU, home to over 1.1m non-British EU citizens, including a large number of families and children. This, according to my team’s ongoing analysis of data from across the EU, is by far the largest conglomerate of non-native EU citizens in the EU.

They come from each and every one of the 27 other EU member states (EU27) and can be found in every sector of the labour market – from museum curators to aristocrats, from professors to hospital nurses, from stay-at-home parents to baristas, from LGTBQ+ activists to retired grandparents.

Freedom of movement for EU citizens across the bloc is one of the pillars of the EU project. Besides the economic rationale, one of the ideas behind the emphasis on freedom of movement is that such mobility will contribute to foster stronger and longlasting bonds across the multitude of peoples, cultures and languages living in the EU. The EU hopes to achieve a sense of shared purpose through fostering a thicker web of personal and intimate connections among citizens of different EU states.

London has been a beacon for this wider project. Brussels, a city that hosts the second largest population of non-native EU citizens, only holds about a quarter of London’s non-native EU citizens. Other European cities follow by a long distance.

London is also, at least demographically, a growing EU capital, as children of EU heritage continue to be born in the city. According to recent ONS data, children born to mothers from the other 27 EU member states represented just under 18% of all births in London in 2018 – well above the figure for England and Wales at 10.6%. In some boroughs, such as Westminster, Brent and Newham, it was above 20%.

At the national level, four EU countries – Poland, Romania, Germany and Lithuania – figure in the 2018 top ten list of birth places for foreign-born mothers.

In our study, my colleagues and I are examining how families with EU27 parents are managing the change and uncertainty brought by the referendum. We’re interested in the kind of family strategies they are putting in place to mitigate the actual and expected impact of the EU referendum on their own circumstances.

Overall, we spoke to over 180 families all over the UK, roughly one third of them in London, in line with the distribution of the EU population in the UK. Many interviewees shared their frustration with us at being invisible, caricatured or misrepresented in the Brexit debate.

Family portraits

Fifteen families based in London also joined an audio-visual photo portrait series called In the Shadow of Brexit which we’ve just published as a book. The aim of the participatory photo project was to capture a glimpse of the diversity of the EU population in the city and to explore whether the way these people feel about the protracted uncertainty of the Brexit process depends upon the place where they live.

In London, as we had already observed in Scotland, EU nationals feel reassured by the fact that the majority of Londoners voted for Remain in the EU referendum and by the pro-EU and pro-migration narrative pushed by the mayor, Sadiq Khan. Many described London as a world apart from the rest of the country. Some, half-jokingly, even advocated for an independent London that leaves the UK and remains in the EU.

For others, such as Italian academic Gianluca and Russian architect Veronika, not even London will be able to mitigate the impact of Brexit, which will be so hard to make the “London’s bubble burst”.

Despite shared concerns on the disruptive impact of Brexit and the uncertainty surrounding the future, for mixed-race families, there is also an awareness that life may not be easy for them elsewhere in Europe where immigrants and ethnic and religious minorities experience frequent discrimination and are the target of xenophobic and racist political movements. For Mihai, a Roma activist from Romania, this is clear:

Despite things getting worse in the UK as a result of Brexit, London is still one of the best places in Europe for a Roma to live.

For Marie, a French Beninese mother of two married to British-born Paddy:

In London, diversity is a fact of life, and everyone can thrive to live comfortably in their own skin.

Marie and others in mixed-race couples see London as a better and safer place for their children to grow up in. For Thomas, a French Cameroonian father of two:

If you are black and immigrant, Brexit didn’t change much for you. It was already bad before.

His wife, Sonia, echoed his point, explaining: “Because he is black, and I’m white, Brexit doesn’t feel the same”. However, both agreed that for their children, Zoe and Leo, London is a better place to grow up in than most cities in France.

As reflected in the views of our interviewees, London’s superdiversity offers a safer and more welcoming space than elsewhere in Europe for EU citizens from every social, cultural and ethnic background to meet, mobilise and build relationships, including intimate ones.

London is a unique and yet fragile laboratory of a possible “Europolitanism”, but Brexit and the new geopolitics emerging with it pose a serious, potentially even fatal, challenge to this future.![]()

Nando Sigona, Professor of International Migration and Forced Displacement and Deputy Director of the Institute for Research into Superdiversity, University of Birmingham

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.

26 Comments

Pingback: ice casino

Pingback: Happy Teacup Pomeranian Puppies Ready For Adoption

Pingback: cozy jazz

Pingback: บอลยูโร 2024

Pingback: ประตู wpc

Pingback: ข่าวกีฬา

Pingback: 누누티비

Pingback: เทรดทอง

Pingback: sex 12 tuổi

Pingback: DG Casino มาตรฐานระดับโลก

Pingback: เว็บเครดิตฟรี โปรแจกหนัก

Pingback: ผ้า

Pingback: ติดตั้งสถานีก๊าซ

Pingback: thailand tattoo

Pingback: SkyWind ค่ายเกมสล็อตมาแรง

Pingback: thewin888

Pingback: arena breakout challenger

Pingback: 보증업체

Pingback: ทำไมต้องเลือกเล่นสล็อตกับ Playtech สล็อต

Pingback: บาคาร่าเกาหลี

Pingback: รวม เว็บหวยจ่าย1000 ที่น่าสนใจ

Pingback: สล็อต เครดิตฟรี

Pingback: healthy lifestyle

Pingback: โปรโมชั่นฝาก 10 รับ 100

Pingback: pgslot

Pingback: โคมโรงงาน