Lawrence Torcello, Rochester Institute of Technology

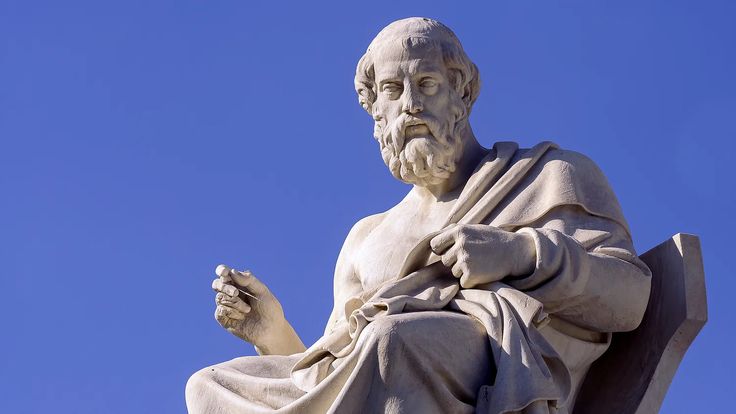

Plato, one of the earliest thinkers and writers about democracy, predicted that letting people govern themselves would eventually lead the masses to support the rule of tyrants.

When I tell my college-level philosophy students that in about 380 B.C. he asked “does not tyranny spring from democracy,” they’re sometimes surprised, thinking it’s a shocking connection.

But looking at the modern political world, it seems much less far-fetched to me now. In democratic nations like Turkey, the U.K., Hungary, Brazil and the U.S., anti-elite demagogues are riding a wave of populism fueled by nationalist pride. It is a sign that liberal constraints on democracy are weakening.

To philosophers, the term “liberalism” means something different than it does in partisan U.S. politics. Liberalism as a philosophy prioritizes the protection of individual rights, including freedom of thought, religion and lifestyle, against mass opinion and abuses of government power.

What went wrong in Athens?

In classical Athens, the birthplace of democracy, the democratic assembly was an arena filled with rhetoric unconstrained by any commitment to facts or truth. So far, so familiar.

Aristotle and his students had not yet formalized the basic concepts and principles of logic, so those who sought influence learned from sophists, teachers of rhetoric who focused on controlling the audience’s emotions rather than influencing their logical thinking.

There lay the trap: Power belonged to anyone who could harness the collective will of the citizens directly by appealing to their emotions rather than using evidence and facts to change their minds.

Philipp von Foltz/Wikimedia Commons

Manipulating people with fear

In his “History of the Peloponnesian War,” the Greek historian Thucydides provides an example of how the Athenian statesman Pericles, who was elected democratically and not considered a tyrant, was nonetheless able to manipulate the Athenian citizenry:

“Whenever he sensed that arrogance was making them more confident than the situation merited, he would say something to strike fear into their hearts; and when on the other hand he saw them fearful without good reason, he restored their confidence again. So it came about that what was in name a democracy was in practice government by the foremost man.”

Misleading speech is the essential element of despots, because despots need the support of the people. Demagogues’ manipulation of the Athenian people left a legacy of instability, bloodshed and genocidal warfare, described in Thucydides’ history.

That record is why Socrates – before being sentenced to death by democratic vote – chastised the Athenian democracy for its elevation of popular opinion at the expense of truth. Greece’s bloody history is also why Plato associated democracy with tyranny in Book VIII of “The Republic.” It was a democracy without constraint against the worst impulses of the majority.![]()

Lawrence Torcello, Associate Professor of Philosophy, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

29 Comments

Pingback: สมัคร สล็อตออนไลน์

Pingback: https://affiliate.softwarepundit.com/redirect?link=https://tocab.de

Pingback: Bk8

Pingback: ชีทราม

Pingback: วิเคราะห์บอลวันนี้

Pingback: พรมปูพื้นรถยนต์ toyota yaris cross

Pingback: ข่าวกีฬา

Pingback: sideline

Pingback: rpt789

Pingback: whatsapp ....+1 (720) 213-6817

Pingback: バンコク不動産

Pingback: ร้านทำเล็บเจลใกล้ฉัน

Pingback: 온라인카지노사이트

Pingback: โบท็อกราคา

Pingback: MM88BET คือเว็บอะไร?

Pingback: ข้อดีของการ เลือกเล่น คาสิโน wm

Pingback: Superslot ใหม่ล่าสุด

Pingback: สล็อตเกาหลี

Pingback: Blockchain

Pingback: บาคาร่าเกาหลี

Pingback: ฝาก 10 รับ 100

Pingback: Med1ical

Pingback: buy weed edinburgh

Pingback: LSM55 เล่นตรงไม่ผ่านเอเย่นต์

Pingback: Lamborghini detailen

Pingback: Lucky neko คืออะไร

Pingback: Fruit Cash

Pingback: casino

Pingback: ทดลองเล่นสล็อต