Ruben Andersson, University of Oxford

At the US-Mexico border, President Donald Trump’s migration “emergency” has led to children being locked up and a threatened trade war. In Libya, now the frontline of Europe’s own migration “crisis”, people are being detained in horrific conditions as the UN warns of a “sea of blood” amid cuts and crackdowns on rescues in the Mediterranean.

A chronic state of emergency now infects border politics in the West. But our view of how this has come to pass is too narrow. The politics of crisis must be understood as part of a re-mapping of the relationship between Western powers and their historical “backyards”. The objective is now to keep perceived danger at bay, out of sight and out of mind – and at any cost. Almost two decades on from 9/11, ours is a gated-up world: green versus red zone, safety versus danger, citizen versus unwanted intruder.

In my research on security and conflict for my book No Go World, I’ve heard the gate clang shut across borders and distant “danger zones”. At the border barriers in Arizona and Spain, guards have told me how they fight back dramatic entry attempts past “useless” fences. On Lampedusa in 2015, before Italy shut its door to rescue ships, I saw African migrants greeted by biohazard suits, scabies checks and transport to faraway “reception” centres, set behind tall walls. And in danger zones such as conflict-hit Mali, I met European soldiers cowering behind similar walls while insurgents roamed the hinterland.

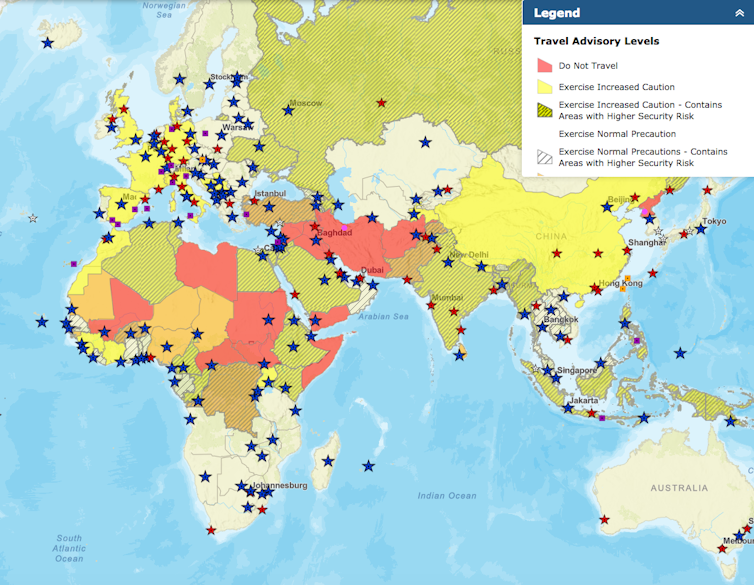

Maps deepen the divide. On the news, larger-than-life jihadist figures loom across Syria or the Sahara. In travel risk advisories, red blotches of no-go advice bleed across the map while border agencies and think tanks add threatening arrows depicting flows of migration or contraband. Their maps speak of encroaching danger – of how, as former US Vice President Joe Biden put it, the “wolves” are slavering at the door.

US State department website

Maps tell stories about our world, and the fearful tale of today’s danger maps is haunted by older ones. On medieval European maps of the world, or mappaemundi, monstrous figures roamed the margins. In the “age of discovery”, blank spaces on the maps spurred on colonial conquest before giving way to boastful cartographies of empire. Today, the connected world of Google Earth coexists with maps of danger that thrive on distancing and division. In our globalised era, blank spaces are paradoxically re-emerging.

The ‘banana of badness’

The end of the Cold War was the catalyst. As the Soviet foe perished, assorted pundits and neoconservatives set out on a search for “monsters to destroy”. Among them was journalist Robert Kaplan, who prophesied that a “criminal anarchy” would soon become the real strategic danger. President Bill Clinton listened, and so did his successor George W. Bush. On the eve of the Iraq invasion, one Pentagon strategist blithely divided the world into a connected “core” and a dangerously disconnected “gap” which must be brought into line by force. The world of counter-terror and border walls had found its map of doom.

However, the security interventions staged in the red zones and along the borders have made things worse. As the “war on terror” escalated, so did worldwide terror fatalities. As Washington ramped up border security, more Mexicans stayed in the US and became long-term undocumented migrants. And as Europe spent years “fighting migration”, migrant desperation and smuggling networks were entrenched. One European police attaché told me in 2010 that “we’re in the eye of the cyclone now … when you bolt all doors, you’ll have a pressure cooker”. His prophecy, for one, proved correct.

But instead of changing tack, Western powers double down with each new “crisis”. They reinforce security operations, escalate the rhetoric and sharpen the divides. Consider EU foreign affairs chief Federica Mogherini, who calls the Sahel and Horn of Africa the “one single place” where Europe has to invest all its efforts to combat irregular migration and terrorism. In such turns of phrase – which I have heard time and again from high officials – any sense of local society is washed aside, replaced by swathes of danger stretching across a bewildering array of countries. This “arc of instability” has become so commonplace that it has even received its own moniker in UK Foreign Office backrooms: the “banana of badness”.

Dealing with this banana ripe with badness is a messy business, as I saw in Mali. In the capital, Bamako, everyone – from border officials to peacekeepers, aid workers and counter-terror operatives – was busy bunkering up. In this cut-price version of Baghdad’s green zone, Western aid managers “produce reports and create new little strategies” to “justify their salaries”, as one scathing official put it. European military officers have retreated into intelligence gathering while badly equipped Africans face attacks by insurgents on the frontlines. Amid this remote-controlled “security”, violence has proliferated and local anger grown – leading the interveners to retreat further behind their bunker walls.

Shifting blame

The divided maps reinforce this picture through what psychoanalysts would call projection – it’s others who are at fault. But this is a fallacy. Danger is not geographic but systemic, and those who intervene are part of this system. Western interventions – from NATO’s campaign in Libya to Washington’s war on terror and meddling in Central America – have directly contributed to instability in the “red zones”.

The first to note this were those on the frontline. In his military barracks in Bamako, an officer told me: “It’s NATO which went along and did all that in Libya, and it’s Europe which has let all these terrorists loose,” fomenting insurgency in Mali. His voice rose as he pointed at the TV, which showed the advances of Islamic State in Iraq: “It’s you! It’s you!”

He was both right and wrong. Right, in that much as in colonial times, today’s divided map allows for the disastrous blowback of interventions to be shifted onto poorer “buffer zones” – and the Sahel has become just such a zone. Wrong, in that the politics of danger creates vested interests both in the West and in those buffer zones.

Unscrupulous Western politicians can ramp up the fears at home for political ends, but so can enemies and “partner states” in fighting migration or terrorism. The higher the value attached to fighting one perceived danger or other, the higher the price that is charged to prevent hell from breaking loose. The result is a merry-go-round of danger feeding on danger, as seen from Turkey to Libya and the Sahel.

An exit from the bunker must start by reversing the negative spiral via different incentives, and a different narrative. In short, we need a new map. But for now, Mali’s President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta will have the last word. Asked by a journalist what he would tell those French citizens who thought the country’s counter-terror operation in the Sahel was too expensive, his answer was: “That Mali is a dam and if this dam breaks, Europe will be flooded.”![]()

Ruben Andersson, Associate Professor in Migration and Development, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

4 Comments

Pingback: beef online

Pingback: Angthong National Marine Park

Pingback: unieke reizen

Pingback: หาฤกษ์ผ่าตัด