Her own text: “Finished with the last meeting in DC, with advisers in the Trump campaign. I now have a new, great enthusiasm for the message.”

Ferdig med siste møte i DC, med rådgivere i Trump-kampanjen. Jeg har nå en ny, stor entusiasme for budskapet.. pic.twitter.com/LgRJSJcOMf

— Tina Bru (@HoyreTina) September 23, 2016

It looked just like any posed political picture. The politician, in this case the National Party’s newly elected leader, Todd Muller, standing by a bookcase. So far so normal. It wasn’t even a new photo.

Except that clearly visible in the lower left-hand corner was a powerful piece of political symbolism – a red Make America Great Again (MAGA) hat.

“He refuses to put it on for a picture, for obvious reasons.” The story that kicked off MAGA-hat-gate, by @awbraaehttps://t.co/UMocJ7Z6Wj

— The Spinoff (@TheSpinoffTV) May 24, 2020

Nothing to see here, Muller responded when questioned about the hat’s significance. It was just a souvenir from Donald Trump’s America; he had Hillary Clinton memorabilia too.

The debate quickly became tribal: the offence taken reflected the left’s obsession with identity politics, it was a Wellington beltway issue nobody else cared about, the hat was about nothing more than Muller’s interest in US politics.

Muller has subsequently said he found Trump’s style of politics “appalling” and the hat will be retired from view. That it didn’t necessarily reflect Muller’s own views was possibly why the Labour-led government didn’t play on the controversy.

Read more:

Third time’s the charm for Joe Biden: now he has an election to win and a country to save

But people were curious, which meant Muller was forced to spend too much of his first weekend as leader explaining it.

Suddenly he was not in control of the agenda. And if he’d really wanted to convince people the hat didn’t matter he might have been better off, as the Islamic Women’s Council advised, to leave it at home. The council’s Aliya Danzeisen put its case succinctly:

That hat represents the denial of the freedom of beliefs. That hat represents the denial of minority voices. That hat represents the vitriol that has been harming that nation and has been harming the world for the last four years.

From whichever perspective, the hat – and Muller’s defence of owning it – brought his political judgement into question.

Perception is reality in politics

Understanding the power of symbolism in politics is important for any leader. It was why people cared about the hat but not the Clinton campaign badge Muller also brought back from his trip to observe the 2016 US election.

www.shutterstock.com

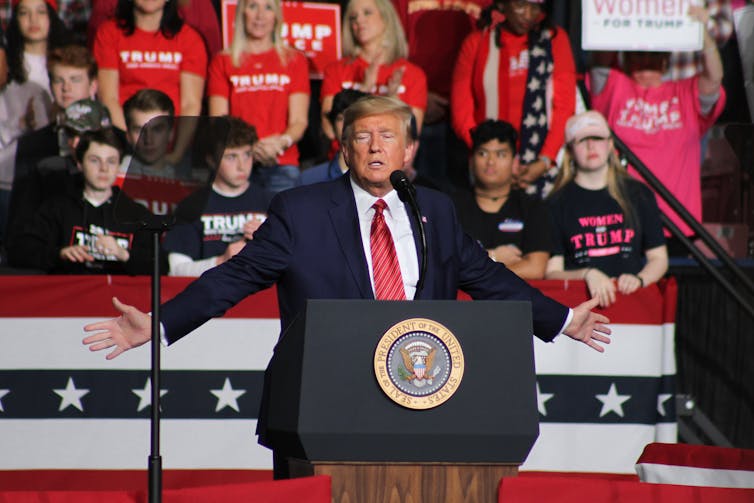

The MAGA hat has become a symbol of violence, division and exclusion. Those were not the values Muller set out in his speech accepting his party’s leadership last week:

Fundamentally I don’t believe that for each and every one of us to do better, someone else has to be worse off.

Nor were those the values that will re-engage women, ethnic and religious minorities who, according to recent opinion polls, are among those who have shifted their support from the National Party to Labour.

Read more:

Donald Trump’s short-lived coronavirus poll bump reveals his fundamental vulnerability

Swinging voters are by definition in the middle. They are not part of Trump‘s base. But if they are not part of Muller’s New Zealand he won’t get to form a government after the election in September.

Muller knows who these people are. He wanted to appeal to “the people who help their elderly neighbours with the lawns on the weekend, the dad who does the food stall at the annual school fair, the mum who coaches a touch rugby team”.

Some of them are the sorts of people MAGA rallies target.

No ordinary souvenir

New Zealand politics can be passionate, of course. Racism and misogyny have their influence. In 2004, then National leader Don Brash showed the power of divisive rhetoric with his “Orewa speech” that alleged Maori privilege. He took his party’s poll ratings from 28% to 45%.

Brash confronted what he called a Maori “birthright to the upperhand”. In fact, Maori politics was concerned only with a birthright to be Maori.

For women, for ethnic and religious minorities, and for whoever else there might be political mileage in vilifying, the MAGA hat also represents the denial of a birthright to be who they are.

Read more:

Donald Trump blames everyone but himself for the coronavirus crisis. Will voters agree?

The MAGA hat and the movement that wears it represent a denial of the liberty at the heart of the American dream. The message is clear: you don’t belong.

That is why the MAGA hat is no ordinary symbol of partisan politics. And it takes on a particular resonance when displayed in a parliamentary office. It represents the violent expression of anti-democratic ideals.

Here’s Todd Muller’s full response re the MAGA cap from my interview yesterday. pic.twitter.com/peISJrWE3g

— Kristin Hall (@kristinhallNZ) May 23, 2020

At another tactical level, the hat is problematic. If National’s biggest obstacle is Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s well-regarded and so far effective response to the COIVD-19 pandemic, why get too close to a president whose leadership of the pandemic response has been among the most ineffective in the world?

Because in politics perceptions count. So too do distractions. Like the perception that Muller is trying to create that Ardern’s cabinet is full of “empty chairs” – and which may be gaining early traction.

But encouraging the perception that he has a broad, inclusive and distinctive vision for economic recovery was what Muller most needed to be doing right away. That would have been more effective than defending his ownership of a hat that is emblematic of the opposite of each of those aspirations.![]()

Dominic O’Sullivan, Adjunct Professor, Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, and Associate Professor of Political Science, Charles Sturt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

23 Comments

Pingback: kojic acid soap

Pingback: บอลยูโร 2024

Pingback: torqeedo electric motor|achiles boat|achillies inflatable boat|yamaha vmax 2021|avon boats|achilies boats|achillies inflatable boats|200 hp merc outboard|avon inflatable boats|avon boat|avon inflatable boat|honda boats|200hp mercury outboard|achillies inf

Pingback: สล็อตแตกง่ายสล็อตเว็บตรงสล็อตpg

Pingback: cornhole

Pingback: สมัคร LSM99 ระบบออโต้

Pingback: โรคหนังแข็ง

Pingback: he said

Pingback: Smith and Wesson 9mm

Pingback: เเทงบาสออนไลน์ บนมือถือ

Pingback: wing888

Pingback: รักษาสิว

Pingback: escape from tarkov cheat

Pingback: สล็อต เครดิตฟรี

Pingback: จุดเด่นของ การเดิมพันกับเว็บ จี คลับ มีอะไรบ้าง ?

Pingback: betflix wallet

Pingback: ufa789

Pingback: นัดเด็ก

Pingback: league88

Pingback: ufabet777

Pingback: เว็บพนันออนไลน์เกาหลี

Pingback: The Pedo-in-Chief Socialist Kamerat Krasnov aka @realDonaldTrump is all over the Epstein list - Bergensia

Pingback: Why are MAGAs and right-wings so angry? - Bergensia