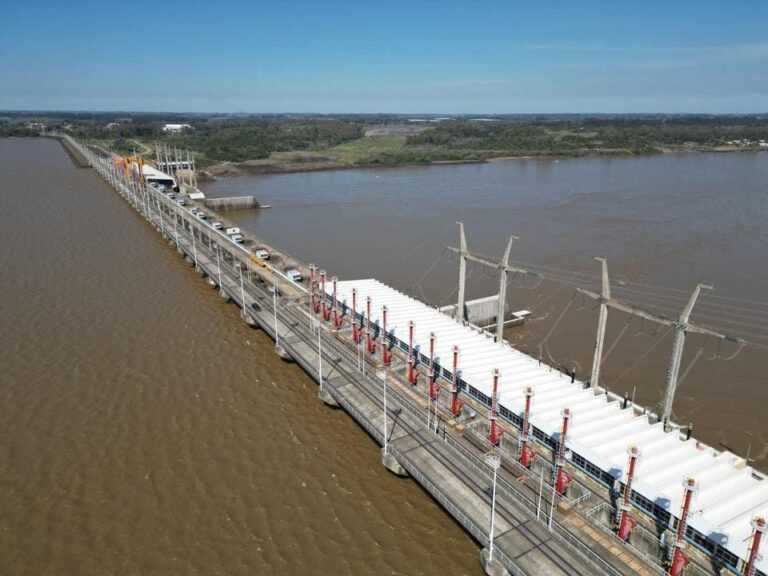

China produces the vast majority of solar cells sold worldwide. The Chinese government has also built renewable energy projects in many Latin American countries and other developing regions.

AFP via Getty Images

Jay Gulledge, University of Notre Dame; University of Tennessee

You might not know it from the headlines, but there is some good news about the global fight against climate change.

A decade ago, the cheapest way to meet growing electricity demand was to build more coal or natural gas power plants. Not anymore. Solar and wind power aren’t just better for the climate; they’re also less expensive today than fossil fuels at utility scale, and they’re less harmful to people’s health.

Yet renewable energy projects face headwinds, including in the world’s fast-growing developing countries. I study energy and climate solutions and their impact on society, and I see ways to overcome those challenges and expand renewable energy – but it will require international cooperation.

Falling clean energy prices

As their technologies have matured, solar power and wind power have become cheaper than coal and natural gas for utility-scale electricity generation in most areas, in large part because the fuel is free. The total global power generation from renewable sources saved US$467 billion in avoided fuel costs in 2024 alone.

As a result of falling prices, over 90% of all electricity-generating capacity added worldwide in 2024 came from clean energy sources, according to data from the International Renewable Energy Agency.

At the end of 2024, renewable energy accounted for 46% of global installed electric power capacity, with a record 585 gigawatts of capacity added that year — about three times Texas’s total generating capacity.

Health benefits of leaving fossil fuels

Beyond affordability, replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy is healthier.

Burning coal, oil, and natural gas releases tiny particles and toxic gases into the air; these pollutants can make people sick. A recent study found air pollution from fossil fuels causes an estimated 5 million deaths worldwide a year, based on 2019 data.

For example, using natural gas to fuel stoves and other appliances releases benzene, a known carcinogen. The health risks of this exposure in some homes are comparable to secondhand tobacco smoke. Natural gas combustion has also been linked to childhood asthma, with an estimated 12.7% of U.S. childhood asthma cases attributable to gas stoves, according to one study.

Fossil fuels are also the leading sources of climate-warming greenhouse gases. When they’re burned to generate electricity or run factories, vehicles, and appliances, they release carbon dioxide and other gases that accumulate in the atmosphere and trap heat near the Earth’s surface. That accumulation has been raising global temperatures and causing more heat stress, respiratory illnesses, and the spread of disease.

Electrifying buildings, cars, and appliances, and powering them with renewable energy, reduces these air pollutants while slowing climate change.

So what’s the problem?

Despite the demonstrated economic and health benefits of transitioning to renewable energy, regulatory inertia, political gridlock, and a lack of investment are holding back its deployment in much of the world.

In the United States, for example, major energy projects take an average of 4.5 years to permit, and approval of new transmission lines can take a decade or longer. A large majority of planned new power projects in the U.S. use solar power, and these delays are slowing them down.

The 2024 Energy Permitting Reform Act, introduced by Sens. Joe Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, and John Barrasso, a Republican from Wyoming, to speed approvals, failed to pass. Manchin called it “just another example of politics getting in the way of doing what’s best for the country.”

An even bigger challenge faces developing countries whose economies are growing fast.

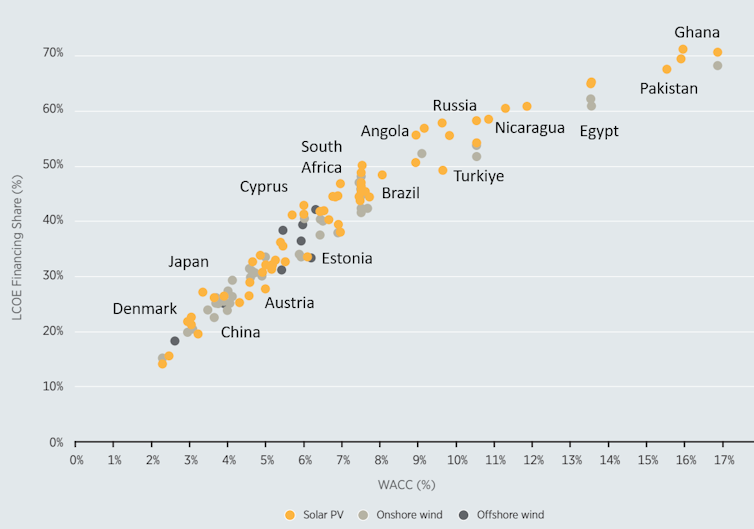

These countries need to meet soaring energy demand. The International Energy Agency expects emerging economies to account for 85% of added electricity demand from 2025 through 2027. Yet renewable energy development lags in most of them. The main reason is the high price of financing renewable energy construction.

In many developing countries, wind and solar projects cost more to finance than coal or gas. Fossil projects have a longer history, and financial and policy mechanisms have been developed over decades to lower lender risk for those projects. These include government payment guarantees, stable fuel contracts, and long-term revenue deals that help guarantee the lender will be repaid.

Both lenders and governments have less experience with renewable energy projects. As a result, these projects often come with weaker government guarantees. This raises lenders’ risk, so they charge higher interest rates, making renewable projects more expensive upfront, even if they have lower lifetime costs.

To lower borrowing costs, governments and international development banks can take steps to make renewable projects a safer bet for investors. For example, they can maintain stable energy policies and use public funds or insurance to cover part of the lenders’ investment risk.

Without international cooperation to lower financial costs, developing economies could miss out on the renewable-energy revolution and lock in decades of rising greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuels, worsening climate change.

The path ahead

To avoid the worst effects of climate change, countries have agreed to cut their greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades.

Achieving this goal won’t be easy, but it is significantly easier now that renewable energy is more affordable in the long run than fossil fuels.

Switching the world’s power supply to renewable energy and electrifying buildings and local transportation would cut about half of today’s greenhouse-gas emissions. The other half comes from sectors where it is harder to cut emissions — steel, cement and chemical production, aviation and shipping, and agriculture and land use. Solutions are being developed but need time to mature. Good governance, political support, and accessible finance will be critical for these sectors as well.

The transition to renewable energy offers significant economic and health benefits alongside lower climate risks — if countries can overcome domestic political obstacles and work together to expand financing for developing economies.![]()

Jay Gulledge, Visiting Professor of Practice in Global Affairs, University of Notre Dame; University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.