Omer Aijazi, University of Toronto

The United Nations has called for an immediate global ceasefire to “put armed conflict in lockdown” and focus on protecting the most vulnerable from the spread of COVID-19. Yet tragically, there are cases around the world where violations have occurred.

Ongoing developments in Kashmir include a crackdown on Kashmiri journalists, rising policing powers, and enhanced curfew measures. These actions suggest that the Indian government may be exploiting the pandemic to accelerate its settler-colonial ambitions in the disputed territory.

For the past six years, I have worked as a researcher along the Line of Control (LoC) — the de-facto border that divides Kashmir into India and Pakistan. I am also on the board of directors for the advocacy organization, Canadians for Peace and Justice in Kashmir.

Thousands of Kashmiris live within a 10-kilometer radius of the LoC, which is so heavily militarized that it is visible from space.

Kashmiris are vulnerable to both the contagion and the violence of the ongoing conflict.

War during a pandemic

In April, the Indian army set up artillery weapons deep in Kashmiri villages, as far as 60 kilometers from bunkered areas, to launch long-distance fire on Pakistan-controlled Kashmir.

This encroachment is creating widespread panic and anxiety. Locals are protesting the shifting of heavy artillery guns into their communities, fearing retaliatory fire from the Pakistani army.

It is an intentional strategy to station soldiers and artillery among communities to make it difficult for the Pakistani army to retaliate. The blurring of civilian and military targets amounts to a war crime.

The Indian army has used civilian populations as a human shield before. In 2017, footage emerged of a Kashmiri man tied to a military vehicle patrolling a Kashmiri town.

As Indian and Pakistani forces continue to exchange fire, widespread loss of civilian life and property is being reported on both sides of the LoC.

During the exchange of cross-border fire, families are forced to take shelter in community bunkers. These are small enclosed spaces that make social distancing practices impossible to follow.

Furthermore, people trying to escape their villages during bombardment are prevented from leaving by the police as they enforce COVID-19 lockdown measures.

Asia’s Berlin Wall

The LoC, also known as Asia’s Berlin Wall, does not constitute a legally recognized international boundary. It was put in place in 1949 as a temporary measure until the status of Kashmir is resolved.

In her book Body of Victim, Body of Warrior, Cabeiri deBergh Robinson, associate professor of South Asian studies at the University of Washington, explains that in earlier years, the LoC was permeable and fluid. It was only after the Simla Agreement in 1972, that it came to mimic the impermeability of a border.

‘100 little sleeps’

From 1990-2003, during the peak of the Kashmiri insurgency, the LoC was a site of intense conflict between Indian and Pakistani militaries.

Armies fired long-range artillery and mortar shells at each other, killing and harming civilians, property, and livestock in the process.

Even though a shaky ceasefire was reached in 2003, skirmishes flare up unannounced.

During my research in the Neelum valley in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, a villager described living near the LoC: “We are never at ease. The firing can start at any time. It’s like having 100 little sleeps every night.”

The number of civilians killed on each side of the LoC is challenging to document, given a lack of government transparency.

The United Nations Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) is responsible for monitoring the ceasefire. India stands accused of blocking UNMOGIP’s access to the LoC.

This year alone, India has committed 882 ceasefire violations.

Pre-existing inequality

Pandemics do not occur in a vacuum but exacerbate pre-existing inequalities.

Kashmir is ill-prepared to handle the pandemic. In Indian-occupied Kashmir, there is one soldier for every nine people but only one ventilator for every 71,000 people, and one doctor for every 3,900 people.

Health facilities along the LoC are severely deficient, reflecting India and Pakistan’s neglect of the sub-region.

Given the current suspension of high-speed 4G internet, Kashmiris are prevented from accessing necessary public health information needed to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Internet and telecommunication services are restricted on both sides of the LoC.

Kashmir’s annexation

Amid the pandemic, on Mar. 31, India introduced a new domicile law. This is one of the many legislative changes set by India following the unilateral abrogation of Article 370 in August last year.

The domicile law paves the way for demographic flooding in Kashmir, which will allow non-Kashmiris to obtain property, compete for government jobs and impact the outcomes of a referendum on Kashmir’s future should it be held.

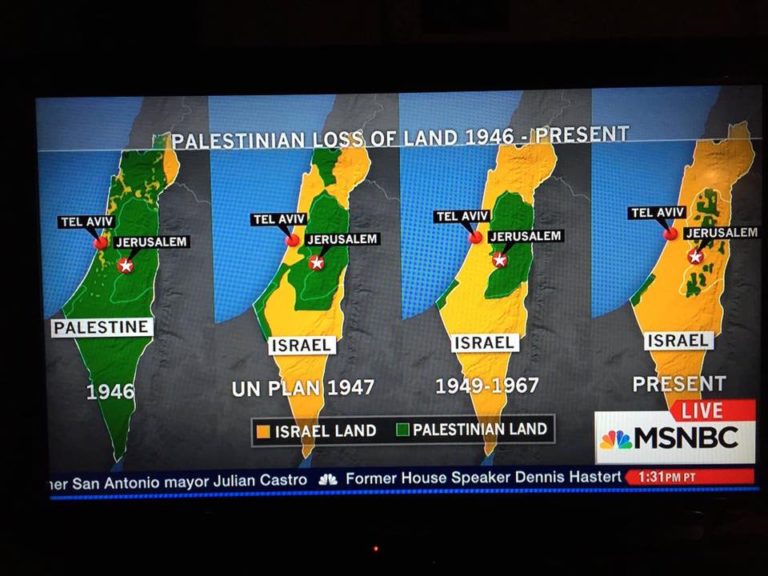

Demographic flooding as a colonial strategy has been used by Israel along the West Bank as well as China in the Xinjiang autonomous region.

A Kashmir yet to come

The pandemic has inspired thinking on the complete restructuring of our world. It has shed light on the centrality of care workers and those at the forefront of our food systems.

It is forcing us to imagine “a world we do not yet know and cannot describe” as scholar Vafa Ghazavi recently wrote.

A just world won’t emerge as if by magic. We will need to fight for it.

The LoC does not signal the closure of Kashmir’s forms and futures. It is a site of potentiality, for a Kashmir yet to come.

This Kashmir would not be held back by the paucity of our imagination or the lack of available language. It would be a Kashmir where Kashmiris can freely choose learning, laughter, and living.

Omer Aijazi, Postdoctoral research fellow, Religion and Anthropology, University of Toronto

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.