Ruth McKie, De Montfort University

While much of the world now recognises the needfor immediate action, there are still those who question the scientific consensus on climate change and deter efforts to tackle it. As might be expected, they have the attention of US President Donald Trump and his Republican administration.

The Heartland Institute’s International Conference on Climate Change was held at the Trump International Hotel in Washington DC on July 25 2019. The Heartland Institute considers itself one of “the world’s leading free market think-tanks”, which “promotes free market solutions to social and economic problems”. It’s perhaps best known for its climate scepticism.

Discussions at the annual event include disputing scientific observations on climate change, criticising “climate alarmists” and promoting fossil fuels. As the choice of venue might suggest, the arguments made here seem to overlap with what the president and the ruling Republican Party has previously said on climate change.

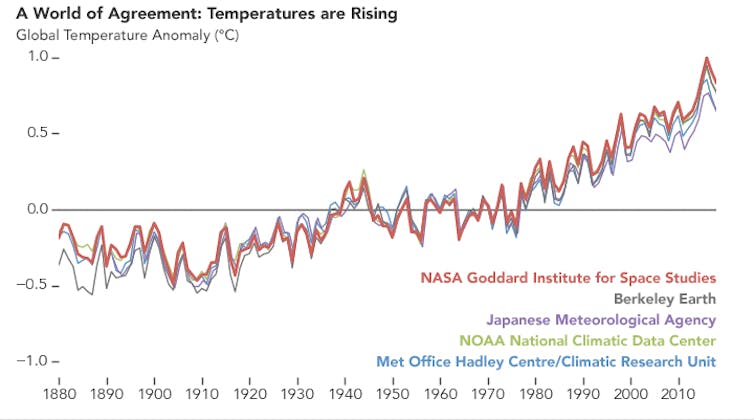

NASA’s Earth Observatory

From my background studying criminal behaviour, I found something striking about the way Trump justifies inaction on climate change. Through his own words, the president’s arguments mimic patterns in criminal behaviour that criminologists call “techniques of neutralisation”.

Criminologists contend that criminals use techniques of neutralisation to help deny or justify a crime they have committed. These five techniques were first defined in 1964 from the types of arguments given by young people in the criminal justice system when justifying their actions.

- Denial of responsibility – it is not the offender’s fault.

- Denial of injury of harm – the crime does not cause significant harm or may have positive results.

- Denial of victim – there is no clear victim.

- Condemnation of the condemner – the offender criticises the criminal justice system to avoid criticism of the offender.

- Appeal to higher loyalties – deviant behaviour was in aid of a greater good or to benefit someone else.

Photographee.eu/Shutterstock

When we flip the context from petty criminals to powerful politicians and lobbyists, it’s not hard to see the same pattern emerging.

- Denial of responsibility – climate change is happening, but humans aren’t the cause.

- Denial of injury or harm – there’s no significant harm caused by human action and there may even be some benefits.

- Denial of victim – there’s no climate change and so no victims, but if such victims of climate change victims existed, they’d deserve to be victimised.

- Condemnation of the condemner – climate change research is misrepresented by scientists, and manipulated by the media, politicians and environmentalists.

- Appeal to higher loyalties – economic progress and development are more important than preventing climate change. This will help protect us from energy poverty and allow developing nations to prosper.

Deception trumps climate action

How can a criminologist’s perspective help us understand how President Trump and climate deniers obscure the scientific consensus on climate change? I believe it helps us see their statements in a new light. Rather than being ill-informed interventions on the topic, Trump’s words reflect a deliberate attempt to shift blame, erase the plight of those already suffering from climate change and turn the fire on climate scientists who study the problem.

In tweets, speeches, and in conversations with journalists, these patterns appear to play out. When denying responsibility for tackling the climate problem, external competitors like China make for a useful scapegoat.

Trump’s comments on climate change often deflect blame, but they may just as often question if it’s happening at all. This ambivalence helps to undermine concerns that climate change will cause a great deal of harm to people in the US and worldwide.

I believe that there’s a change in weather and I think it changes both ways ….

There’s no credible possibility that climate change isn’t happening, but by engineering a false sense of uncertainty about the science, Trump can condemn those condemning him for inaction – the climate scientists themselves.

Don’t forget, it used to be called global warming, that wasn’t working, then it was called climate change, now it’s actually called extreme weather because with extreme weather you can’t miss.

The poorest are predicted to suffer the worst consequences of climate change in the US, but by withdrawing the world’s largest economy from the Paris Climate Accords, Trump argues he is standing up for these people by acting in their best interest.

The Paris climate accord is simply the latest example of Washington entering into an agreement that disadvantages the United States to the exclusive benefit of other countries, leaving American workers – who I love – and taxpayers to absorb the cost in terms of lost jobs, lower wages, shuttered factories, and vastly diminished economic production.

Given the grave consequences of the US doing nothing on climate change, should deflecting blame, sowing uncertainty and condemning experts on such a scale be labelled criminal? I believe that these perceived similarities – between how offenders justify their behaviour to the criminal justice system and how Trump justifies his position on climate change to the world – are no coincidence. We shouldn’t always read ignorance in what Trump says – it might suit him and climate deniers more than we think.

Ruth McKie, Lecturer in Criminology, De Montfort University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

22 Comments

Pingback: Buy Turkey tail mushroom capsules Michigan

Pingback: วิเคราะห์บอลวันนี้

Pingback: jazz instrumental

Pingback: บรืษัทกำจัดปลวก ชุมพร

Pingback: โปรโมชั่น LSM99

Pingback: Check it out here

Pingback: post read

Pingback: เว็บไซต์สล็อต

Pingback: เช่ารถตู้พร้อมคนขับ

Pingback: Bilad Alrafidain

Pingback: ตรวจดาวน์ซินโดรม

Pingback: โคมไฟ

Pingback: company website

Pingback: Buy Anabolic Steroids Online

Pingback: Ford Everest

Pingback: สล็อต เครดิตฟรี

Pingback: article

Pingback: marbo 9000 puff

Pingback: สินเชื่อรถบรรทุก

Pingback: link

Pingback: Pharmaceutics1

Pingback: สล็อตวอเลทเติมวอผ่านอั่งเปา