Miguel de Felipe Toro, Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC); Carmen Díaz-Paniagua, Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC), and David Aragonés Borrego, Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC)

Wetlands are among the most biodiverse yet endangered ecosystems on Earth. In the last century alone, around 70% of them have disappeared, with overexploitation of aquifers being the main threat in many cases.

The Doñana National Park lies on the right bank of the Guadalquivir River mouth in southern Spain. It represents the most important wetland in Western Europe, covering 543 km2 (209.65 sq mi) of protected area. The park owes its importance to its marshes, house to thousands of breeding and wintering waterbirds, and to its ponds, which host many rare, endemic, and endangered species.

For more than 20 years, numerous researchers have warned of the environmental risk posed by excessive urban and agricultural growth surrounding the Andalusian national park.

For this reason, a proposed new law to extend irrigation in its vicinity is of concern to the international community.

The European Commission is again threatening to take Spain back to the Court of Justice of the European Union, which already condemned the country in 2021 for failing to take adequate measures to protect Doñana’s habitats.

Germany, the main import destination for strawberries from Huelva – one of the areas where Doñana is located – decided to send a delegation to find out about the situation – although the visit has been delayed because of the general elections that will take place in Spain at the end of July.

Biodiverse ponds

Most of the Doñana ponds are temporary – they dry up in summer. Yet they are home to highly specialized flora and fauna, with numerous aquatic species that have evolved to withstand dry periods. The great abundance (3,000 water bodies) and diversity ensure species with shorter life cycles and those requiring ponds with long periods of flooding can develop each year. This is why they are listed as priority conservation habitats in the European Union.

There are also a small number of permanent ponds in Doñana that function as a refuge for species during the dry summers while increasing the richness of the system by providing habitat for strictly aquatic species, such as fishes.

The Doñana ponds lie on an aquifer that covers an area approximately five times larger than the park’s surface area. This aquifer is replenished annually by rainfall, raising the water level and flooding vast areas of the park.

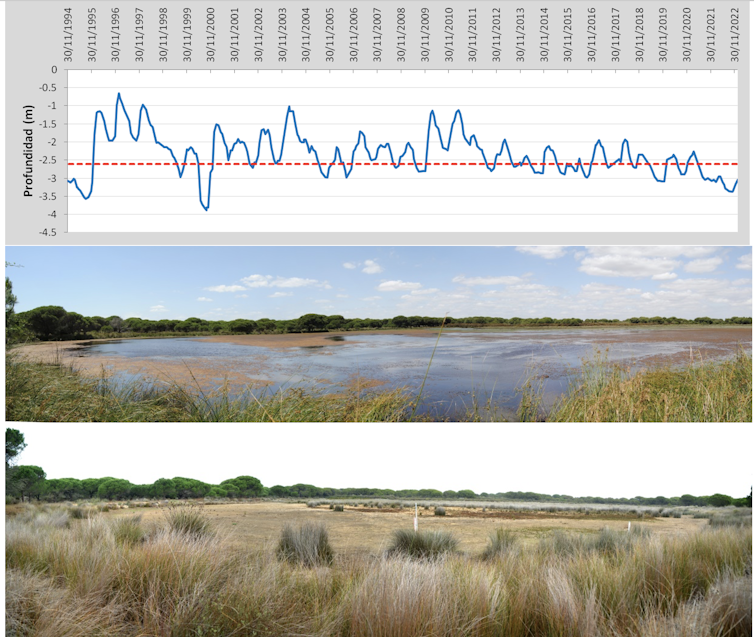

Most of the Doñana ponds are shallow. A decline of more than two meters in the water level means ponds will suffer desiccation and be colonized by shrubs. However, the Guadalquivir basin authority’s monitoring network shows that 13 of the 14 zones into which the area is divided show downward trends in aquifer levels. Some areas show more than 20m declines compared to those measured in the previously known driest period (1995). This has led to an official declaration of over-exploitation of the aquifer, with three of the five bodies that make up the aquifer considered to be at risk.

The effects of construction and agriculture

Doñana has been strictly protected since 1969, yet its surroundings have rapidly changed land use in recent decades. This has had consequences for the state of conservation of the aquifer.

In the 1970s, construction began on a coastal tourist resort occupying more than 360 hectares today. The resort pumps groundwater via pumping stations located less than 1km from the main ponds of the park, which it uses for its guests’ consumption and even to irrigate a golf course that was in operation for 17 years.

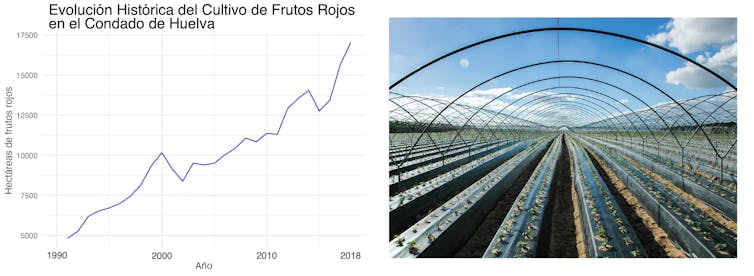

Over the last 30 years, there has also been a five-fold increase in the use of greenhouses to grow strawberries in the area around the park. The greenhouse cover now amounts to more than 11,000 hectares, producing fruit that is distributed across Spain and the rest of Europe. This production has become of great socio-economic importance to the neighboring municipalities.

The water used for these crops also comes from the aquifer, being impossible to estimate the volume of abstractions because, although there are legal water concessions, there are also many illegal abstractions that are not subject to control.

Ponds replaced by scrubland

In a recent study, we analyzed the trends and drivers experienced by the Doñana pond network. Using satellite imagery, we quantified the duration and extent of inundation for each pond larger than 900m² from 1984 to 2018.

These data have allowed us to determine the changes and their relationship with local climate (precipitation and temperature) and anthropogenic factors such as tourist developments, pond distance to groundwater pumping stations, greenhouse crop extension, and the local golf course operation.

We found that 59% of the Doñana ponds have not flooded since at least 2013. Not only do they no longer flood, but as the frequency of flooding has decreased, the basins have been colonized by purely terrestrial vegetation, such as scrubland and pine forests.

Although rainfall and temperature are closely related to pond behavior, 80-83% of the ponds are flooding less and for less time than the annual climatology explains. Water abstractions are the cause of this anomaly. This explains why the general deterioration of the entire pond system affects the pond closest to the urbanization and the cultivated areas most severely.

Pond flooded area was reduced by approximately 70% due to the increase in greenhouse crops in the surroundings, while groundwater abstractions at the coastal resort led to the complete desiccation of the closest ponds. There is also a significant effect associated with the length of time the golf course has been in operation.

Drought worsens the situation

All these deteriorating trends are aggravated in a drought such as the current one, in which the aquifer’s natural recharge is reduced as rainfall decreases, but extractions increase as crops need more water.

Permanent ponds are thus now behaving as temporary ones, and most of the temporary ponds have not even been filled this year. In the pond’s dry basins, we observe how the scrubland that colonized them is also drying up. Even centenary cork-oak trees formerly held Doñana’s renowned heronries are dying. The system, which in past decades was able to recover from intense periods of drought, does not seem to be able to withstand the current pressures.

Doñana is in a critical situation and requires urgent action. Many years have gone by without any control of the abstractions from the aquifer, despite the numerous studies and experts who warned about the negative effects that groundwater abstractions could exert on Doñana’s conservation.

We are now once again witnessing how the name of Doñana is used as an excuse for new political confrontations. And again, further delays arise in taking action to save Doñana’s aquifer, ponds, and wildlife.![]()

Miguel de Felipe Toro, Investigador predoctoral en Ecología de Humedales, Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC); Carmen Díaz-Paniagua, Investigadora del Departamento de Ecología y Evolución, Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC), and David Aragonés Borrego, Técnico especialista SIG y Teledetección alumno de doctorado en Geografía, Estación Biológica de Doñana (EBD-CSIC)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments are closed.