Lanterns with messages of peace are lit on the 75th anniversary of the Nagasaki bombing. DAI KUROKAWA/EPA

Gwyn McClelland, University of New England

The UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons will finally come into force after the 50th country (Honduras) ratified it over the weekend. The treaty will make the development, testing, stockpiling and use of nuclear weapons illegal for those countries that have signed it.

This is an extraordinary achievement for those who have suffered the most from these weapons — including the hibakusha (survivors) of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the islanders who lived through nuclear weapons testing in the Pacific.

Since 1956, the hibakusha in Japan, South Korea, Brazil and elsewhere have been some of the most strident campaigners against the use of these weapons. Among them is a group of Japanese Catholics from Nagasaki whom I interviewed as part of my research collecting the oral histories of atomic bomb survivors.

A 92-year-old hibakusha of the atomic bombing of Nagasaki in 1945 and a brother in a Catholic order, Ozaki Tōmei, explained the significance of the treaty to survivors like him. He was orphaned from the bombing at 17 and never found his mother’s body.

The Germans made tools for war including poisonous gas, which was [eventually] banned […] However, when the USA made an atomic weapon, then they … wanted to try it out. It was a war […] they were human.

And so this is why we say we have to eliminate nuclear weapons […] They said they did it to end the war, but for the people who were struck, it was horrific […] there was no need to use it.

Treaty does not have support of nuclear powers

The treaty was adopted at the United Nations in 2017 by a vote of 122 nations in favour, one against and one abstention.

Sixty-nine nations, however, have not signed it, including all of the nuclear powers such as the US, UK, Russia, China, France, India, Pakistan and North Korea, as well as NATO member states (apart from the Netherlands who voted against), Japan and Australia.

Since the treaty was adopted, it needed ratification by 50 countries to come into force. This will now happen in 90 days.

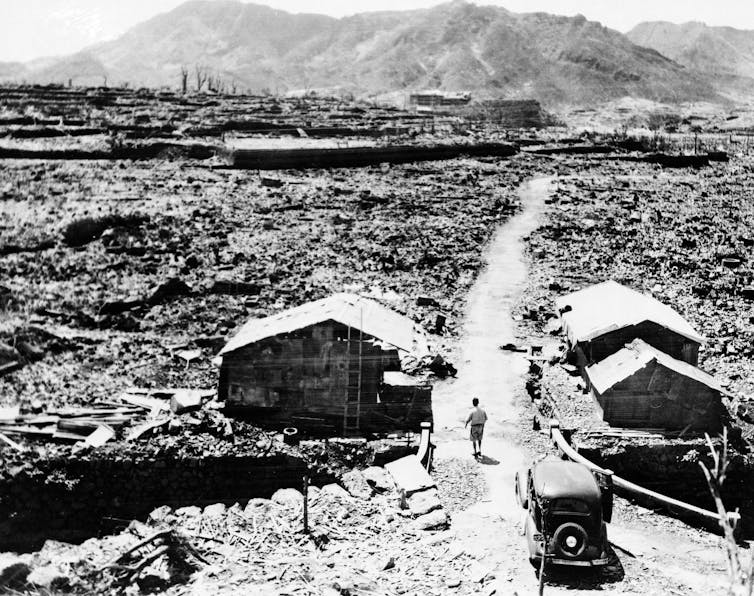

Shacks made from scraps of debris from buildings that were leveled in the aftermath of the atomic bomb that was dropped over Nagasaki. AP

Shacks made from scraps of debris from buildings that were leveled in the aftermath of the atomic bomb that was dropped over Nagasaki. APThe campaign for the treaty has relied heavily on civil society and organisations such as the Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (ICAN).

And from the beginning, it has exposed political fault lines. The United States has been particularly outspoken in its opposition to the treaty, warning last week the treaty “turns back the clock on verification and disarmament and is dangerous” to the 50-year-old Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT).

Read more:

World politics explainer: The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The NPT sought to prevent the spread of nuclear arms beyond the five original weapons powers (the US, Russia, China, UK and France). It has been signed by 190 countries, including those five nations.

The head of ICAN, Beatrice Fihn, says the new treaty banning nuclear weapons merely builds on the nonproliferation treaty.

There’s no way you can undermine the nonproliferation treaty by banning nuclear weapons. It’s the end goal of the nonproliferation treaty.

States like Japan and Australia have opposed the treaty on the grounds their security is boosted by the US stockpile of nuclear weapons. Japan’s former prime minister, Shinzo Abe, has said the treaty

was created without taking into account the realities of security.

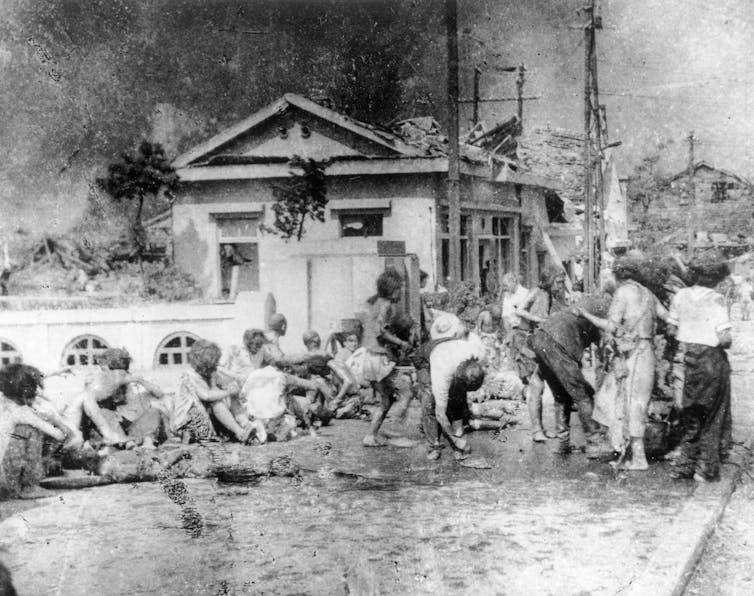

Survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bomb await emergency medical treatment. AP

Survivors of the Hiroshima atomic bomb await emergency medical treatment. AP

The efforts of hibakusha in advocating for a treaty

Making the bomb illegal turns an old US justification for the weapon on its head. Harry Stimson, the former US war secretary, argued in 1947 the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were necessary to compel the Japanese to surrender at the end of the second world war.

The atomic bomb was more than a weapon of terrible destruction; it was a psychological weapon.

The damage from the bombings was colossal. It is unknown how many people were killed, but estimates range from 110,000 (the US army’s toll) to 210,000 (the figure accepted by ICAN and others).

Read more:

Ban the bomb: 70 years on, the nuclear threat looms as large as ever

At the forefront of the campaign to support the nuclear weapons ban treaty have been the voices of hibakusha who experienced the carnage firsthand.

Another Catholic hibakusha, Nakamura Kazutoshi, told me the stockpiling of nuclear weapons enables states to carry out genocide.

In war, we are at a level below animals. Among monkeys, or chimpanzees, there are no animals who would carry out a genocide.

Nakamura Kazutoshi. Author provided

Nakamura Kazutoshi. Author providedA third hibakusha, 90-year-old Jōji Fukahori, told me about how he lost his mother and three younger siblings in the Nagasaki bombing.

His younger brother, Kōji, died an excruciating death around a week after the bombing, walking in the hot ash with no shoes and complaining to his brother, “I’m so hot!”

At the site where Fukahori’s brother was exposed, the temperature was about 1,000 degrees Celsius. Fukahori said,

You would have thought everyone would have turned into charcoal.

For Fukahori, the lasting effects of radiation exposure is a major reason why nuclear weapons must be banned. He continued:

the terror of radiation has to be fully communicated … The atomic bomb is unacceptable. I still cannot get over it.

Since 2009, Fukahori has been speaking out at the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and on the Peace Boat, a non-governmental organisation that organises cruises where passengers learn about the consequences of using nuclear weapons from hibakusha.

Pressure building on Japan

The Japanese government is now under mounting pressure to ratify the treaty. Major Japanese financial institutions and companies have said they will no longer fund the production of nuclear weapons and nearly a third of all local assemblies have adopted proposals calling on the government to act.

The government, however, has been unmoved. In August, Abe gave a speech at a memorial service in Nagasaki, in which he suggested the effects of the bombings had been overcome.

Seventy-five years ago today, Nagasaki was reduced to ashes, with not a single tree or blade of grass remaining. Yet through the efforts of its citizens, it achieved reconstruction beautifully as we see today. Mindful of this, we again feel strongly that there is no trial that cannot be overcome and feel acutely how precious peace is.

Visitors pray for the atomic bomb victims at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Koji Ueda/AP

Visitors pray for the atomic bomb victims at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Koji Ueda/AP

A Japanese atomic researcher, who knows how Fukahori and other hibakusha have not been able to move on, told me Abe’s words don’t go far enough:

Rather than placing a ‘full-stop’ at the end of damages such as this, we have a necessity to make our claim that the damages are not finished.

The nuclear weapons ban treaty offers a moment of hope for all the hibakusha of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still with us after 75 years. It is certainly their hope the ratification of the treaty now moves us one step closer to a world free of nuclear war.

Gwyn McClelland, Lecturer, Japanese Studies, University of New England

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

B

B

24 Comments

Pingback: ประตูไม้เทียม

Pingback: Best universities in Africa

Pingback: เกม 3D

Pingback: buy cuban magic mushrooms online

Pingback: รับทำเว็บ WordPress

Pingback: land slot auto เว็บตรง

Pingback: ข่าวบอล

Pingback: โปรโมชั่น BRAZIL999

Pingback: สมัครสมาชิกใหม่ LSM99 โบนัส 100%

Pingback: BAU

Pingback: เช่ารถตู้พร้อมคนขับ

Pingback: เสริมจมูก พัทยา

Pingback: jaxx download

Pingback: webcam tokens

Pingback: Money laundering

Pingback: Profibus cable

Pingback: Diyala1 Univer

Pingback: where to get weed in porto

Pingback: bangkok tattoo

Pingback: KUBET

Pingback: i thought about this

Pingback: couples massage

Pingback: n-ethylpentedrone kopen | buy 2mmc | 6 apb pellets | buy 5-mapb | deschloroketamine | 4-mpd (4-methylpentedrone) | 6 apb powder | 2-mmc pellets, 5-mapb | 2-mmc crystalline powder | 4bmc poeder | acheter 3-me-pcp | buy cathinonen | buy 6 apb powder |NEP N-

Pingback: Diaphragm Husky