Authors: Nicholas Allen, Royal Holloway; Erica Consterdine, University of Sussex; Feargal Cochrane, University of Kent; John-Paul Salter, King’s College London, and Maria Garcia, University of Bath

After a summit with her cabinet that sparked several ministerial resignations, British prime minister Theresa May has published a controversial white paper setting out her government’s vision for Brexit. This will now be sent to the European Union for further negotiations. Experts assess the proposals in key areas.

An appeal to party unity

Nicholas Allen, Reader in Politics, Royal Holloway, University of London

The publication of the Brexit white paper is the latest step in Theresa May’s effort to broker a common position for negotiating future UK-EU relations. It is also the latest step in what might be called the Cabinet “peace process”.

Senior ministers have been sniping at each other for months and two cabinet ministers – David Davis and Boris Johnson – have resigned. Tory MPs have been engaging in open civil war. With the clock ticking on the Article 50 negotiations, the prime minister had to reimpose some semblance of collective responsibility.

In many ways, the details in the white paper are less significant than the softer-Brexit direction of travel established at the crunch summit at Chequers that preceded it. Britain is leaving the EU. A sizeable minority of zealot Tory MPs will object to any watering down of their vision of being wholly outside the ambit of EU regulations. Yet, some element of compromise is almost certainly necessary.

It is simply too soon to know whether or not the white paper will bolster or diminish May’s position. Negotiating Brexit and keeping the Tories united was always going to be extraordinarily challenging. In that sense, at least, nothing has changed.

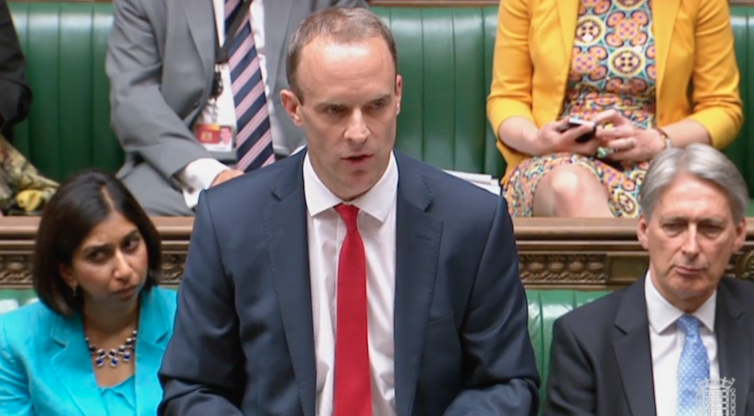

Parliamentlive.tv

Free movement

Erica Consterdine, Research Fellow in the Sussex Centre for Migration Research, University of Sussex

Now to the big bad wolf of Brexit – free movement of people. The key issues of the Brexit debate on immigration have been the rights of EU citizens residing in the UK and vice versa, and the looming labor market crisis following the end of free movement. The white paper reinforces earlier agreements for the rights of EU citizens up until 2020 but makes no attempt to address the impending labor issue.

May has been consistent in the last 18 months that free movement is ending. The government proposes a “mobility framework” but this seems to be little more than a buzzword of which the substance is lacking. The government is rightly waiting for a report from the Migration Advisory Committee due in September to fill in the details.

The framework is effectively just an extension of current policies for nationals of countries outside the European Economic Area. It suggests extending intra-corporate transfer to EU citizens, policies to attract international students and allowing visa-free travel for tourists.

The most novel proposal is to establish a UK-EU Youth Mobility Scheme, presumably on a quota basis. Surprisingly, there was no proposal to reestablish a seasonal agricultural workers scheme – a move that seemed likely in light of recent conclusions from the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee. Key in the paper for wider policy is that reducing net migration remains an ambition, but the explicit target of reducing it to less than 100,000 a year is curiously absent, suggesting the target itself may well finally be abandoned.

Northern Ireland

Feargal Cochrane, Professor of International Conflict Analysis, University of Kent

July 12 was an ironically poignant day to bring this document out. “The Twelfth” is a key date in Northern Ireland, with one section of the community celebrating their Britishness through the commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, when Protestant King William defeated Catholic King James, and the other section (and not just Irish nationalists) going on holiday to escape it. It’s a time of heightened tensions between unionists and nationalists.

The white paper is essentially an attempt to supersede the backstop option on the Irish border, agreed by the British government in December 2017, then disavowed shortly after, and now essentially reframed. There is barely a mention of a UK government alternative to the EU backstop option, or contingency planning if agreements cannot be reached, with most of the focus being on an innovative bespoke approach to future agreements. The Irish government and the EU are likely to push this much more forcefully in their responses to the document.

The main proposal is for a “free trade area” for goods that would establish “continued frictionless access” across the EU and UK for goods. There is much in the white paper that is aspirational (like previous iterations of the UK position). That includes the hope for a deal where “close arrangements on goods should sit alongside new ones for services and digital”.

If the EU wears this (it’s far from certain that it will and certainly not in this form) it would avoid the need for a hard border in Ireland over some – but not all – issues. It’s not clear, for example, how this would relate to the free movement of people. But so much here will depend on how hard the EU returns the serve on the text. Its immediate holding response is that it will consult its EU partners and negotiate.

One problem beyond the substance of the text for the EU, the Irish government and everyone in Northern Ireland, is that who knows what the future will bring. Signing a treaty today does not mean that it will be adhered to tomorrow. So one of the key issues for the Irish government will be the extent to which these commitments on a continued and agreed rulebook with a frictionless border in Ireland can be made as watertight as possible.

This will not be regarded by Ireland or the EU as a take-it-or-leave-it option. It is the start of the negotiation, not the end, and the best the UK government can now hope for is an outcome that is Brexit in name only with alignment (albeit bespoke) in key areas of customs and trade. If the UK government can’t deliver this (and the odds on failure would be high at the moment) Northern Ireland faces a No Deal abyss that will represent the biggest political and economic crisis since Ireland was partitioned by Britain in 1921.

Services

John-Paul Salter, Visiting Lecturer in Public Policy, King’s College London

Overall the white paper succeeds in clarifying the government’s position on services. Unlike goods, services will not be included in the government’s proposed free trade agreement. Instead, it is proposed that a special arrangement is put in place allowing British banks to operate in EU markets.

This will be based on a beefed-up version of mechanisms which are already in place, and which enable the EU to grant access to the banks of non-member states (as the UK will be, after Brexit) if their regulatory frameworks are judged to be “equivalent”. The white paper also makes important suggestions for how these mechanisms can be improved: there are proposals for how cooperation between EU and British regulators can be formalized, for example.

The Bank of England is presumably happy since it would avoid becoming a passive rule-taker. The City will be happy since clarity is better than uncertainty for firms planning their futures. And since, in time, the equivalence provisions might be extended to cover more areas of activity.

Shutterstock

What the EU’s response will be is difficult to judge. At a basic level, the proposal rests on legislative provisions which are already there, so the starting points are clear. More importantly, though, the white paper places great emphasis not on market access (and thus on the continued profitability of British firms), but on systemic stability.

A messy, poorly-executed financial services Brexit would risk disrupting regulatory cooperation, which in turn could threaten the stability of the UK’s and the EU’s financial system. Given the extent of their interconnection, contagion would quickly spread.

Seen in this light, the proposals for enhanced regulatory equivalence, with a view to bolstering institutional cooperation, are eminently sensible. They are also feasible.

On the other hand, since the referendum, several member states – France, Germany, Luxembourg, Ireland – have gone to great lengths to try to attract British firms. They may each covet the prestige and tax revenues that come from hosting a large financial sector. Plus, there is an EU-level move happening, as the European Central Bank and the European Commission are both keen to see the center of gravity of European financial markets return to the mainland. This consideration may well feature in the thinking behind the EU’s response.

Goods

Maria Garcia, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, University of Bath

The initial economic partnership chapter of the white paper recognizes that cross-border transactions post-Brexit will be different from the existing arrangements. However, the degree of difference and additional transaction costs are not highlighted. The UK will seek a free trade area for goods, including agri-food, which will be underpinned by a “facilitated customs arrangement” aimed at a frictionless trade of goods and a “common rule book”. There are still outstanding questions as to how exactly the customs arrangement will work in practice.

The idea is to avoid border checks on goods traveling between the UK and EU and vice versa. The UK would apply any EU tariffs that differ from UK tariffs on goods coming into the UK that are destined for the EU, and then refund them for goods that stay in the UK. This would be a unique situation and it is not evident that the EU will accept this, especially when the white paper’s section on future UK trade policy claims that checks will not be conducted at the border but throughout the country, without explaining how this will work in practice.

The second part of the free trade area proposal, a common rulebook on goods, recognizes the importance of rules on safety, and non-tariff measures that affect trade. It includes a commitment that the institutions which set British standards will not propose standards that conflict with EU ones. This recognition should facilitate further negotiations, despite being deeply unpopular among Brexiters.

The white paper insists on common rulebooks only on rules necessary for frictionless trade at the border, but there is no specification of which rules fall under this category, and which rules will be subject to change. It’s likely that the EU will demand clarification of this, and that the parties’ interpretation of which rules are essential for frictionless trade may vary.

![]() Clarity and agreement on this will be especially important with a view to future trade agreements, as the EU will want to ensure that, for instance, the infamous US chlorinated chickens do not enter its market, not even in the shape of a British-baked pie.

Clarity and agreement on this will be especially important with a view to future trade agreements, as the EU will want to ensure that, for instance, the infamous US chlorinated chickens do not enter its market, not even in the shape of a British-baked pie.

Nicholas Allen, Reader in Politics, Royal Holloway; Erica Consterdine, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Immigration Politics & Policy, University of Sussex; Feargal Cochrane, Professor of International Conflict Analysis, School of Politics and International Relations, University of Kent; John-Paul Salter, Visiting Lecturer in Public Policy, King’s College London, and Maria Garcia, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, University of Bath

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

11 Comments

Pingback: Lying, kleptocrat Boris Johnson needs to be expelled from No 10 - Bergensia

Pingback: cozy coffee shop

Pingback: การให้บริการของ bk8thai

Pingback: naga356

Pingback: APEX cheat

Pingback: remisolleke

Pingback: สมัครเว็บตรง168

Pingback: safe escape from tarkov hack

Pingback: dig this

Pingback: live cams

Pingback: free chat rooms